AT THE BEGINNING

When taking stock of one's life, the logical thing to do is to conjure up your earliest memory. Why not start at the beginning? My earliest memory is looking through the bars of my crib. It was against the wall that bordered the stairway. I had a stuffed donkey named Francis. One time I had dreams about an elephant that lived under my bed. When I told everyone there was an elephant under my bed, they told me I was crazy. I remember standing at the bottom of my bed, peering over the footboard to get a better view of the living room. I remember my grandma in the living room with another white haired woman, and it bothered me that I didn't know who that other woman was. I remember lying in bed early in the morning, listening to Mom and Dad in the kitchen as Dad prepared for work. I remember Dad's tin dome lunchbox with it's coffee thermos that clipped into the lid. I recall the sound of the clip as my dad closed his lunchbox before walking out the front door, leaving for work. One day I figured out how to lower the bars on the side of my crib. Soon after I was given a regular twin bed.

I can see myself sitting on a grey vinyl chair with chrome legs, my chin far enough above the formica table top to no longer require a phone book below my butt. Staring down at me are numerous boxes of cereal, many with the word "SUGAR" unabashedly displayed as part of the title. I lived in a world of cartoon characters. That was the way adults and commercial advertisers drew the line between our world and theirs. But our world was much more exciting and definitely more colorful than theirs.

Tony The Tiger would look down at me to assure me his cereal was G-R-E-A-T! A little boy in a pointed cowboy hat would scream "I want my Maypo!" Cowboy Tom was feeling his Cheerios. Sugar Frosted Flakes, Sugar Crisp and Sugar Smacks all appealed to our passion for candy. Tigers, clowns, bunny rabbits, cuddly bears, Mickey Mouse, Bullwinkle the Moose and others were all conscripted to sell us cereal.

Then there were the cartoons all deliberately scheduled in our free time to keep us busy while Mom was fixing dinner, or on Saturday mornings when we had no school. We all knew who Popeye, Olive Oyl, Bluto Wimpy and Swee'pea were. But the idea that we would eat spinach because it was good for us was still a hard swallow. We sang M_I_C…K_E_Y…M.O.U.S.E, along with the members of our favorite club! The past and future were represented by The Flintstones and The Jetsons. The great outdoors was embodied in two bears named Yogi and Boo Boo who lived in Jellystone Park and Smoky The Bear would remind us that only we can prevent forest fires. To satisfy our need for international intrigue, we had Rocky and Bullwinkle always on the trail of Russian spies Natasha Fatale and Boris Badenov. Woody Woodpecker, Mighty Mouse, Tom and Jerry, Heckle and Jeckle, Bugs Bunny, Huckleberry Hound, Betty Boop and Donald Duck were all our accepted imaginary friends.

CHILDHOOD

When I was growing up there was a lot of talk about the generation gap. In my teens I certainly experienced it personally. Like everything important in my life back then, I wrote about it. Now, going through my things after decades, I have a very different perspective on what I wrote in my teens. I see my notes and writings as a specific message for the me of today. It's an urgent calling from a young man asking me not to forget him the way he feels the adults at the time of his writing had forgotten him. I actually remember making myself a promise back then. I promised I would not be one of those adults who looked at young people as totally naive and unaware. But that would require not forgetting the thoughts and feelings of the young boy I used to be.

It was a cold winter afternoon. Dark clouds were congregating in the west. Each time I inhaled though my nose, there was an undeniable smell of snow in the air. When a large wet snowflake landed on the tip of my nose, quickly turning into a droplet of water, I took my cue. I closed my eyes, extended my arms to each side, then began to spin. The faster I would spin the harder it would snow. I was convinced that I was personally turning up the volume on the snow. I also realized that any onlooker would probably see me as just a silly little boy simply excited by the snow. But I knew on some level that I was exerting an innate ability to not care what other people think. Throughout my formative years I kept reaffirming that promise to not forget the little boy I once was. When I close my eyes I see a young boy spinning around in a snowstorm, connecting to nature in a way that will serve him for the rest of his life. That young boy is neither naive nor unaware.

The very first day of school. Now there's a pivotal moment in a child's life. The teacher instructs us to hold up our hand with one finger if we need to pee, and two fingers if we need to poop! I think I wasted a lot of time trying to remember how many fingers to hold up, in fear I would get it wrong, before I finally realized it didn't really matter. Our textbooks were very well illustrated with a few words on each page in very large print. Across the top of the blackboard were 26 representations of the letters of the alphabet, in capital letters and small letters. The people illustrated in the textbooks were very unthreatening. They became our friends, and there was always a dog named Spot. "See Spot run." "See Spot run fast."

When we get older we take so many things for granted. So what is it that young boy wants me to say on his behalf today. I think he wants to remind us all that the reason we can construct sentences, write letters and build bridges is not only because of great teachers and schools. We can do all these things because all these little people who were thrown into very challenging and sometimes scary situations, rose to the occasion and did what it takes to survive. But most of all, he wants to remind us to get in touch with that place of beauty inside us, where the eyes of a child sees life much more simply.

CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

The year before I started school I was alone with my mother during the day. In the 1950s the television was turned on early in the morning and often was not turned off until the evening. A test pattern came on at 10 PM as stations went off the air. The test pattern squealed a high pitched sound that resembled a phone left off the hook, I suppose it was designed to wake people up. At the top of the test pattern was a picture of an American Indian in full headdress. We never dreamed that one day the TVs would have 24 hour programing that would allow some to leave their televisions on all night.

During my days with my mother the soap operas always played in the background. Guiding Light and Search For Tomorrow were favorites on CBS. I was among the first generation to grow up with TV. In my young developing mind were black and white stories of dysfunctional families interrupted by commercials. At 4 o'clock the cartoons came on, flooded with cereal commercials, all designed to babysit the children who had just arrived home from school. I Love Lucy, Lassie, Make Room For Daddy, The Cisco Kid, The Adventures of Rin Tin Tin and more all occupied time that was previously spent sitting in front of a radio. Adding visuals to stories took away the creative process of imagination. I realized this when my favorite radio programs were converted to TV. I remember feeling angry that the TV versions of my favorite characters were so different than the ones I imagined from the radio. I felt something had been stolen from me.

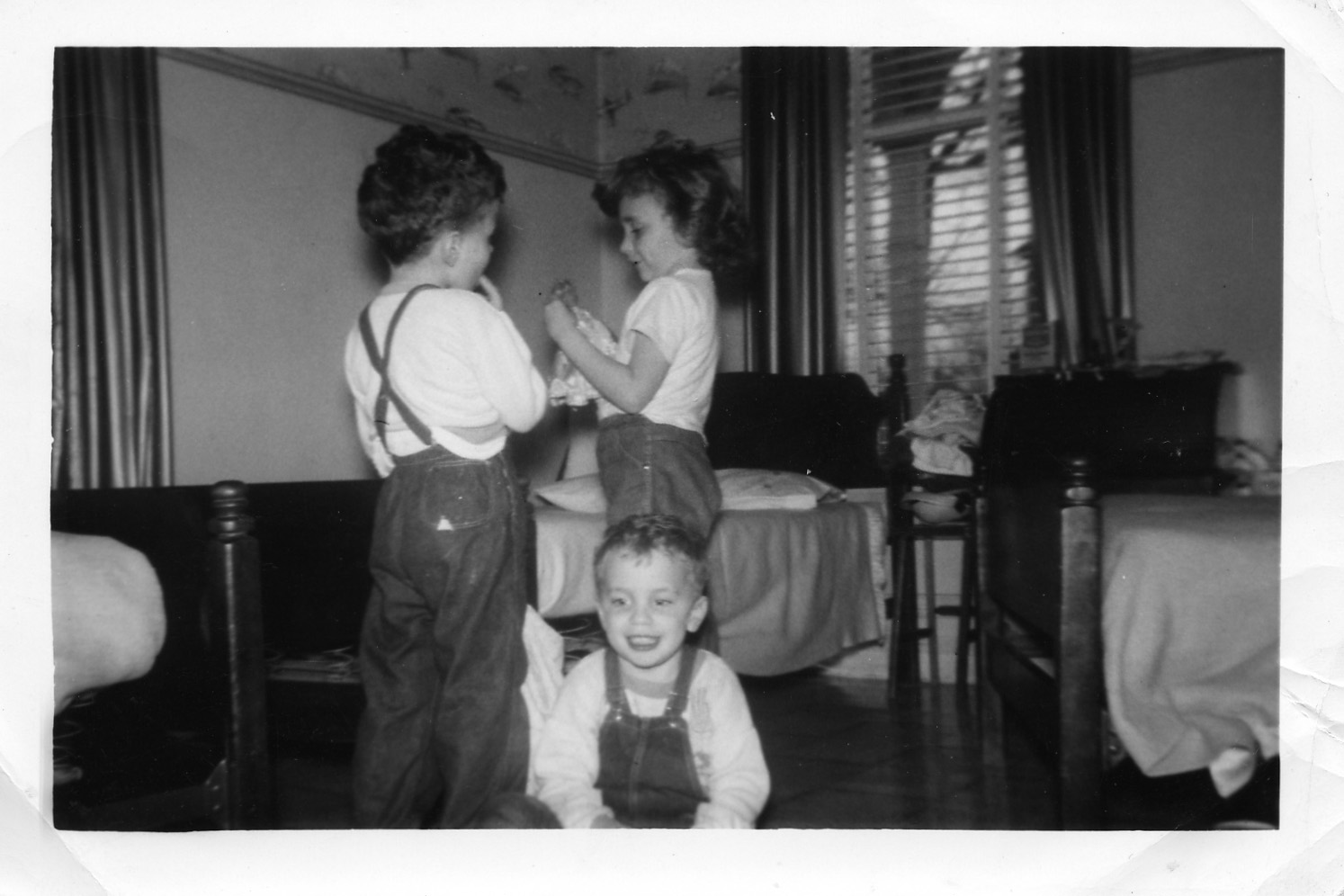

On weekday afternoons my mother would often take me out to the sidewalk as we watched for my sister Sandy and my brother Steve to appear at the corner of Collett and Williams Streets on their ways home from Collett School. With my mother's permission I was allowed to run toward them like a puppy wagging it's tail. After a long day, at last my playmates had returned. Of course as a preschooler, I had no idea what took place at school. I watched my siblings leave for school in the morning and return in the afternoon. I was content with coloring in my coloring books as my sister and brother did homework.

Saturday was our day! Saturday mornings were filled with cartoons, cowboys and Indians and sugary cereals straight from the commercials that informed us which brands to demand from our parents. The very concept of a weekend prepared us for futures of 9 to 5 jobs where we would long for Friday afternoons and two days of freedom. Somehow, even as a child, I knew that was not my destiny. Those few years of radio shows had awakened a part of my brain that needed to be fed with creativity. I was never comfortable with someone else stealing my ability to choose my own visuals. I was more comfortable with a well written book where I partnered with the author to create an imaginary world where I could walk through their narrative.

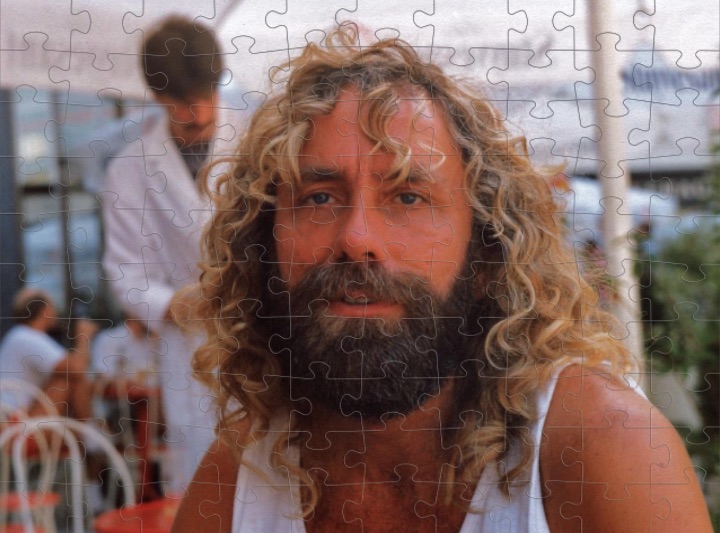

JIGSAW PUZZLE

Facing my own mortality has forced me to look at everything in a different light. I ask myself questions I never even contemplated before. Having looked death in the face, I see more than ever, the importance of living one moment, one day at a time. But it's also important to have purpose in each moment, otherwise we find ourselves just waiting to die. I've seen enough death in my lifetime to have had unanswered questions even before my own experiences at death's door. Perhaps my purpose is to be more sharing than the people I was caregiver for. Standing now on the other side of the fence, I have an opportunity to share some insight.

When I watched my beloved Robby take his last breath, the first thing I noticed was that his beautiful blue eyes had instantly lost their shimmer. I thought to myself, that saying about the eyes being the window to the soul is really true. Then my heart ached for all the knowledge, creativity and compassion that had been an expression of his soul. What is the point if it all just disappears in that last breath? Perhaps that's why I take such pleasure in putting my thoughts down in words. I feel like they are my way of sending something into the future.

I can also attest to the idea of one's life flashing before one's eyes at the moment of death. Another one of the mystical wonders of life is the human brain that stores information from a lifetime of experience, only to be recalled by a familiar scent, taste or picture. In a way I got stuck in my flashback. Maybe that's the best reward of coming back from the dead. I get to take my flashback slow and easy.

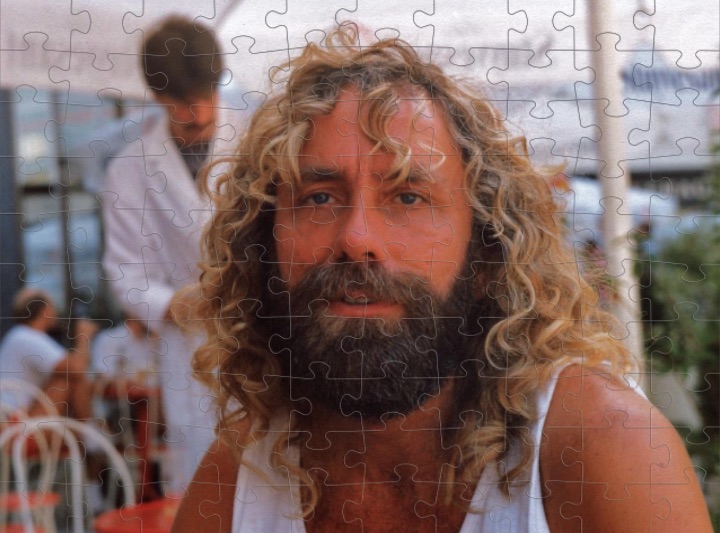

My brain and the attic boxes are inextricably tied together now. Each holds the next clue to some long forgotten memory that perhaps also holds another key to why I am who I am. Like a complicated jigsaw puzzle, I take pleasure in putting the pieces into the proper places, knowing that they all fit snuggly into place, meaning every experience was exactly the way it was supposed to be. Imagine being able to take your last breath without regrets. Perhaps that's why our whole life flashes before us at the moment of death. To show us the value each of us has in the bigger puzzle.

COLLETT SCHOOL

I remember when a really cool guy moved to the neighborhood. His name was James Bone. He combed his hair in a way that was similar to a rock star. Anyway, that's how it seemed to me as a grade schooler. I don't remember how exactly it happened, but I wound up walking to school with James in the mornings. He would wait for me to walk down the alley to join him on Kimball Street. That made me feel really special, that a cool older guy would even bother with me.

Before classes began we would all congregate near the south entrance of the school on Clarence Street. When the doors opened we were required to climb quite a few stairs to get to the first floor classrooms.

At the top of the stairs directly on the right was my fourth grade class with Mrs. Leverenze. I remember looking over at my best friend Sandy while singing "get along little doggies, quit roving around, you've wandered and trampled all over this ground." We would always smile at each other in recognition of our mutual love of that song. Then on the day when we were making paper mache animals late in the spring, I pulled out a scrap of the Chicago Tribune, ready to slather it with paste, when I saw a headline that read "Little Girl Loses Her Life." Sandy's photo stared back at me from the page with that same smile we always shared when singing folk songs. Mrs. Leverenze, noticing my tears, came over and placed her hand on my shoulder as she glanced down at the paper on my desk. "Bless her heart" she said, then walked away. Even now, 61 years later, I can still hear her voice reciting those words.

At the other end of the hallway on the right was Miss Graig's first grade classroom. I still remember the first day of school. A mixed feeling of terror and excitement. All the fragrances of September. The smell of crayons and and paste. The odor of newly fallen leaves crunching under foot. The scent of chalk wafting into the air to the muffled sound of erasers clapping together.

In the winter, the long corridor we called the cloak room was lined with wet coats and mittens, rubber boots and melting snow that created a fragrance like a waiting pot of hot soup, as we transitioned from the cold outdoors to the warmth of our classroom. We would sit on our hands until our fingers stopped tingling.

At noon we would all go home for lunch, where my mom would have sandwiches and Campbell's soup waiting on the table. And of course, a soap opera on the TV! Occasionally we were treated to a school luncheon where mothers volunteered to cook in the kitchen. The smell of hot dogs and baked beans filled the entire school house as we all watched the clock in anticipation. Then we would return to our desks carrying trays of food with a small individual package of potato chips on the side.

Recess was a time when we were all usually given freedom to choose how to spend it. I remember a time when I would sneak over to the big tree that grew just above the retaining wall on Kimball Street. I would jump from root to root as I wound my way around the tree, counting the number of rotations. I imagined that each time around constituted one flight up in a skyscraper. The game was to guess how many stories I could climb before turning around to climb back down in time to go back to class. I was surprised when another boy asked me what I was doing, then joined me in my quest.

One day in third grade, as we were drawing easter pictures, we watched out the window as dark black clouds turned daylight into darkness. We could see the concern on the face of our teacher Mrs. Thiede. Soon the wind was pounding rain and leaves against the windows. Then the emergency sirens went off and we all recited the words we had been taught for a situation like this. "Stay calm and line up single file, then walk to the basement!" We all gathered against the appointed wall as we quietly listened to the whistling and banging sounds upstairs. Then, after what seemed like forever, the sun came shining through the basement windows signaling the "all clear". We returned to our classrooms, ancy with anticipation, waiting to run outside to survey the damage.

My memories of Collett School are mostly good memories. If I had the opportunity to change my life, I think I would leave it alone just the way it is.

COLLETT STREET

The 600 block of Collett Street in the 1950s was the embodiment of the Little Rascals. We played baseball in the vacant lot between my grandmother's house and the Weller's to the north. We played football in the lot in front of the Testa's, two houses to the north. In the summer we would often gather in the back yard of the Roth's, three houses to the south. The vacant lot also provided the space for kick the can at dusk, or a game of badminton or croquet in the afternoon. There were lots of trees in the vacant lot. I can remember to this day, the ones that were climbing trees. Against the warnings of our mothers, we would climb into the trees, straddle a secure limb, hanging out sometimes unseen by passersby on the sidewalk below.

Each child on Collett Street was raised with the awareness of the danger of playing in or near the alleyways. Behind our houses were a trucking company and a factory. Multiple times each day the alleyways would see traffic from semi-trucks. This created a potential disaster in a neighborhood with so many children. That problem was compounded by the fact that the alleyways were paved with gravel full of native American beads uncovered in the strip mines. We children understood the danger of the trucks, but for some reason we decided to take risks for finding beads. Is it just luck or fate that we all survived?

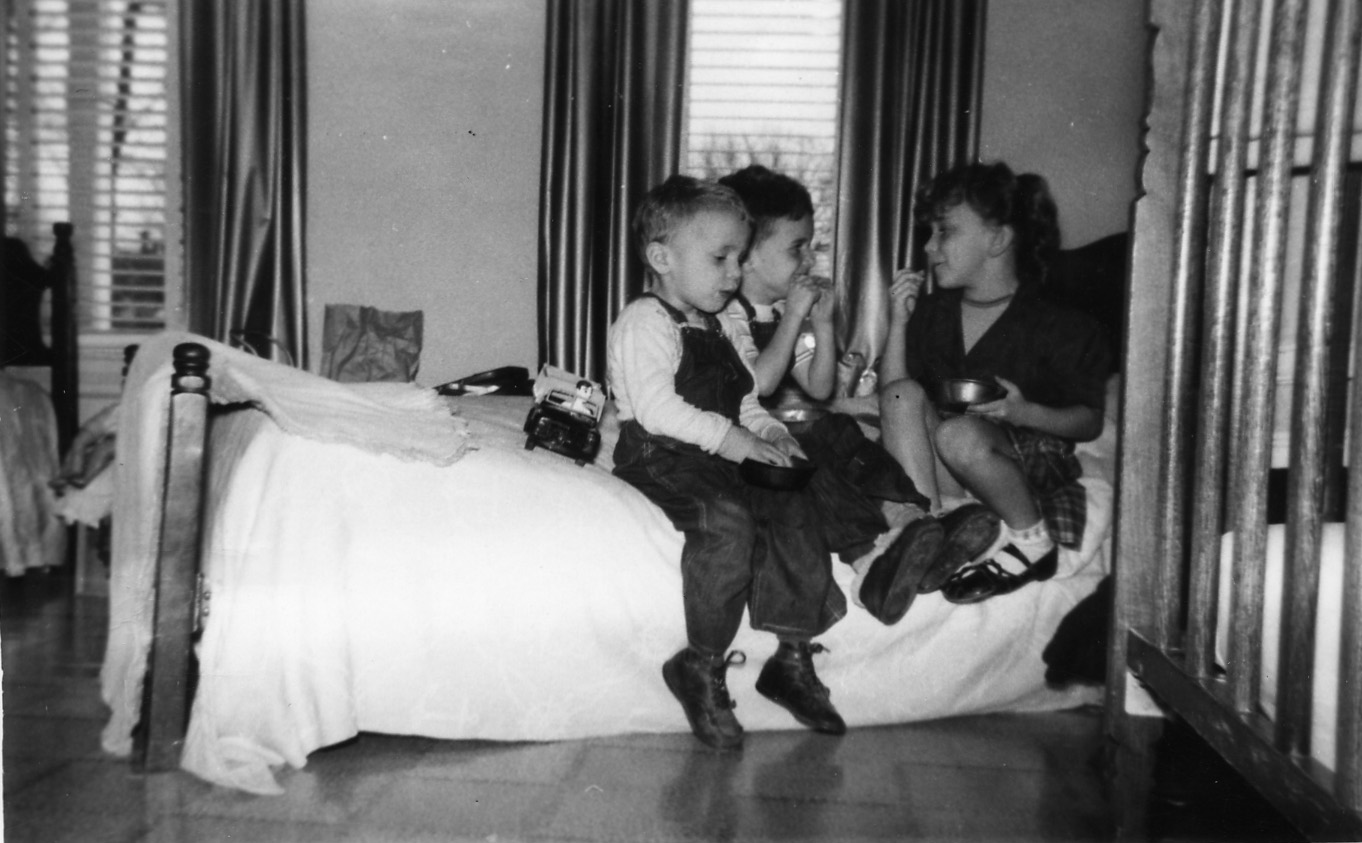

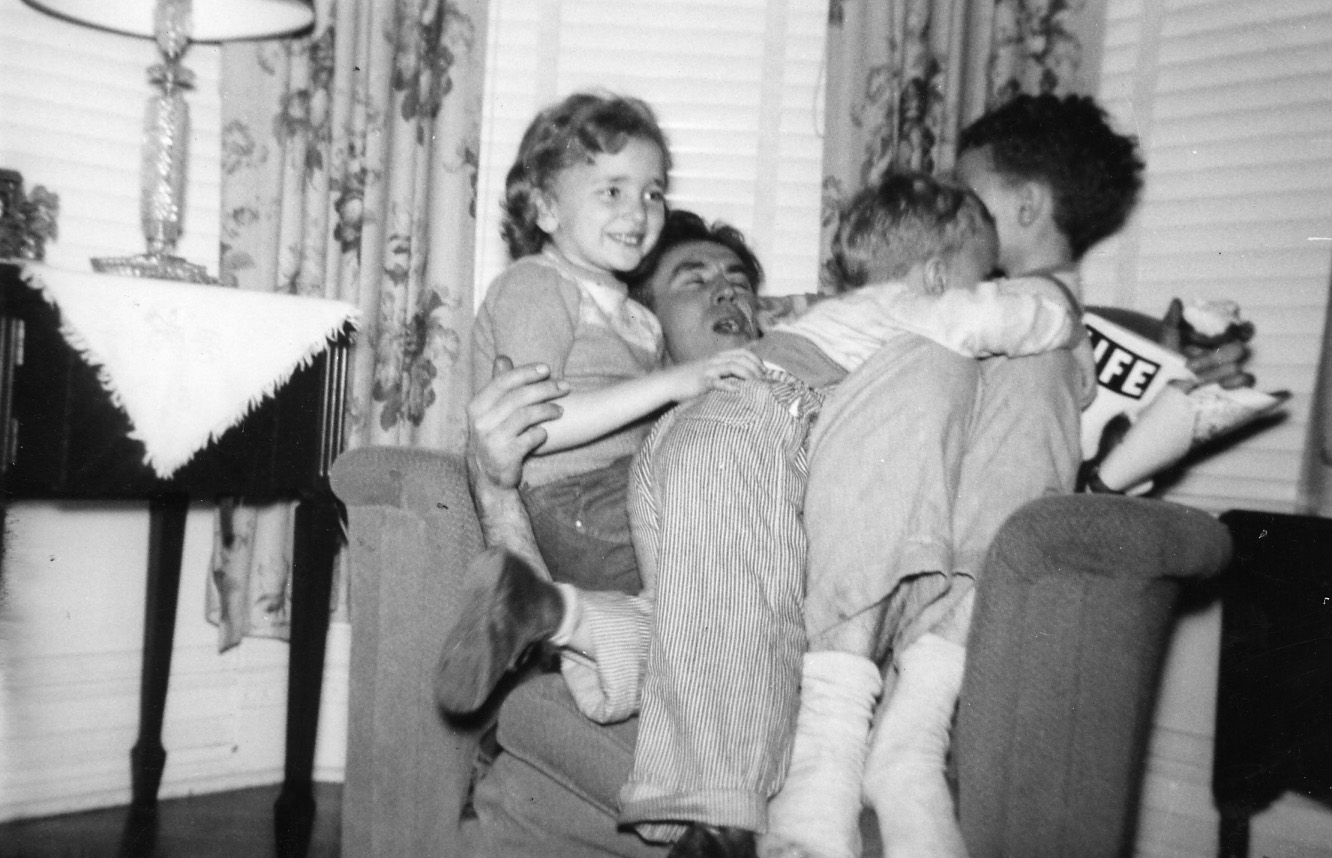

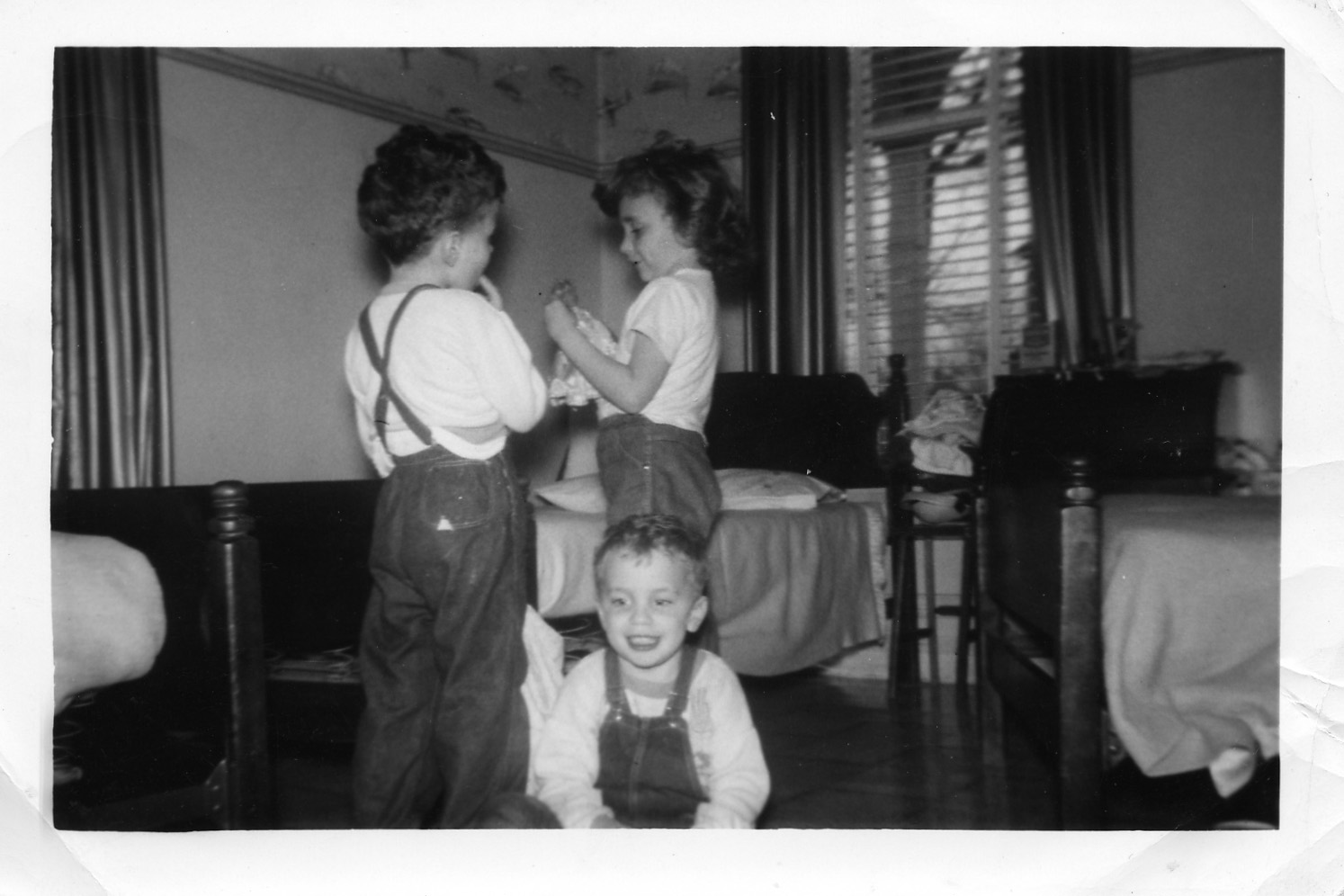

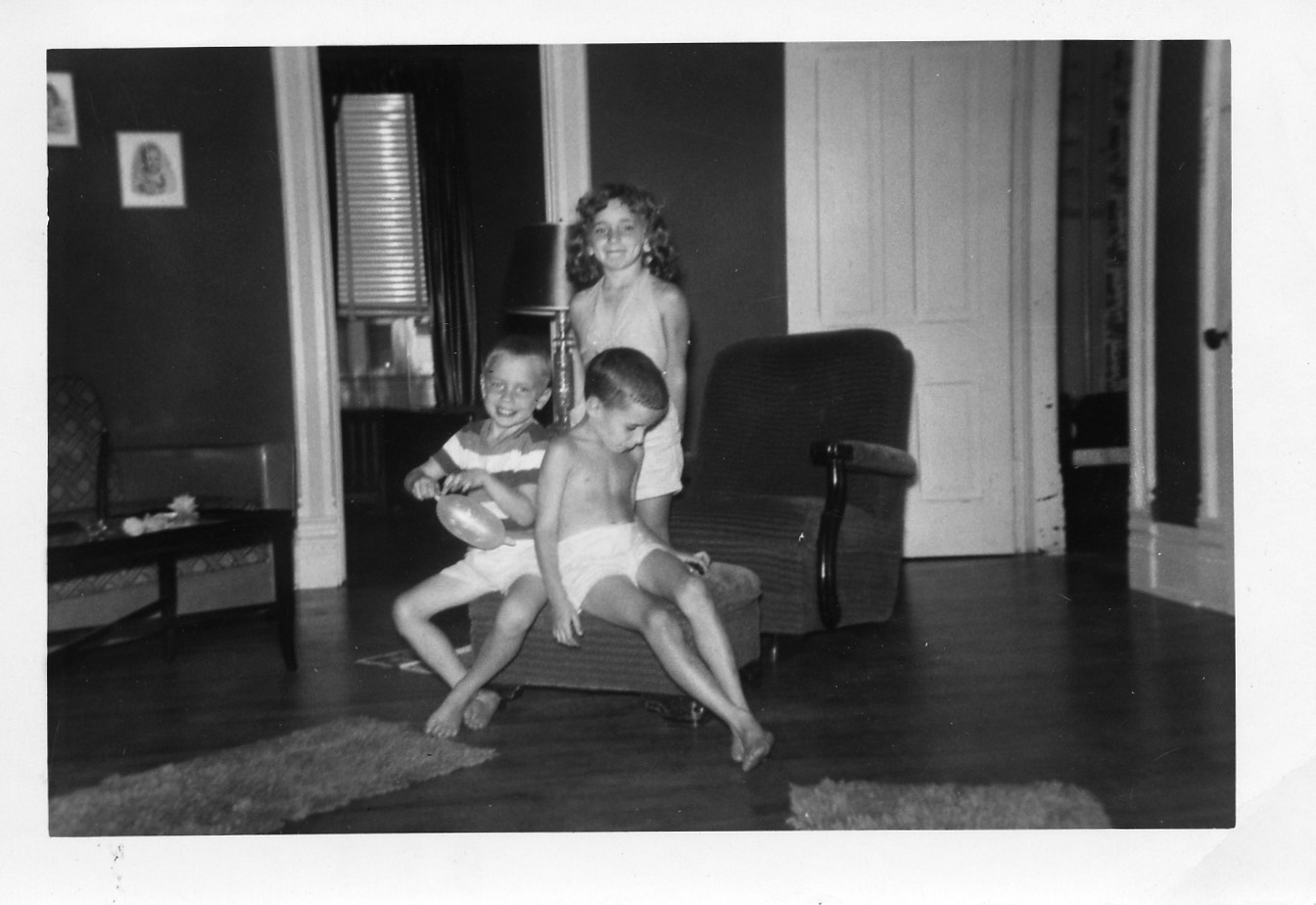

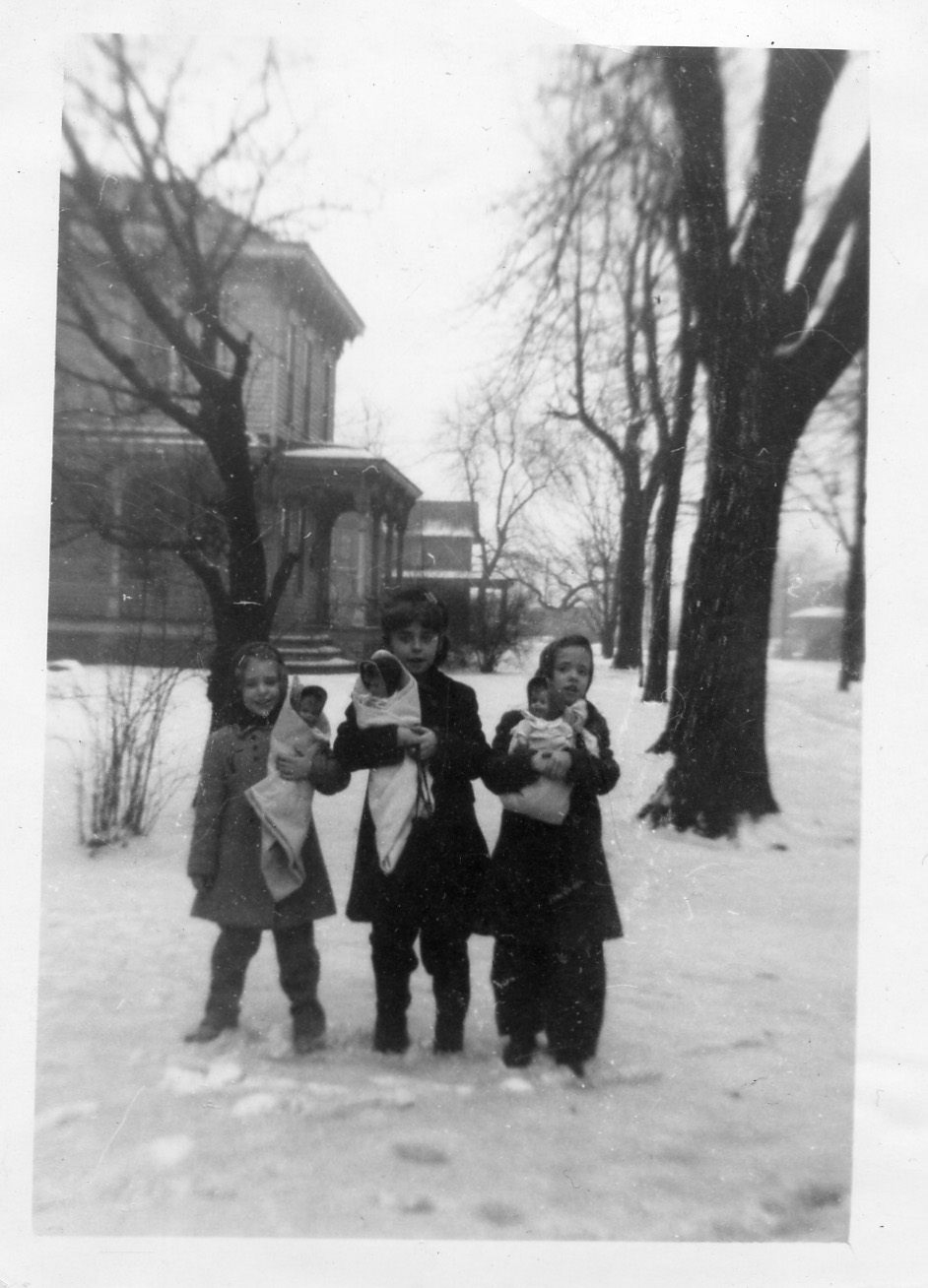

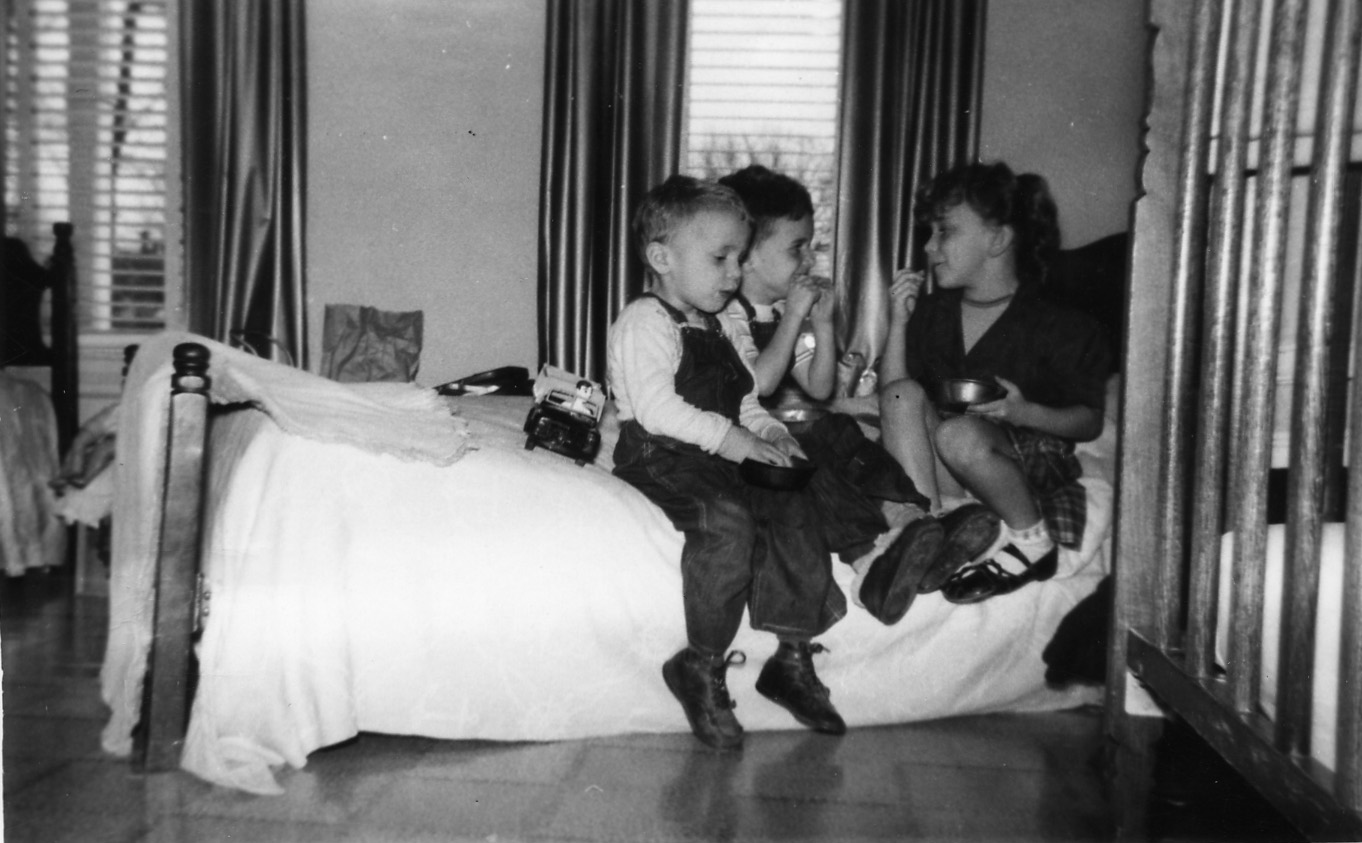

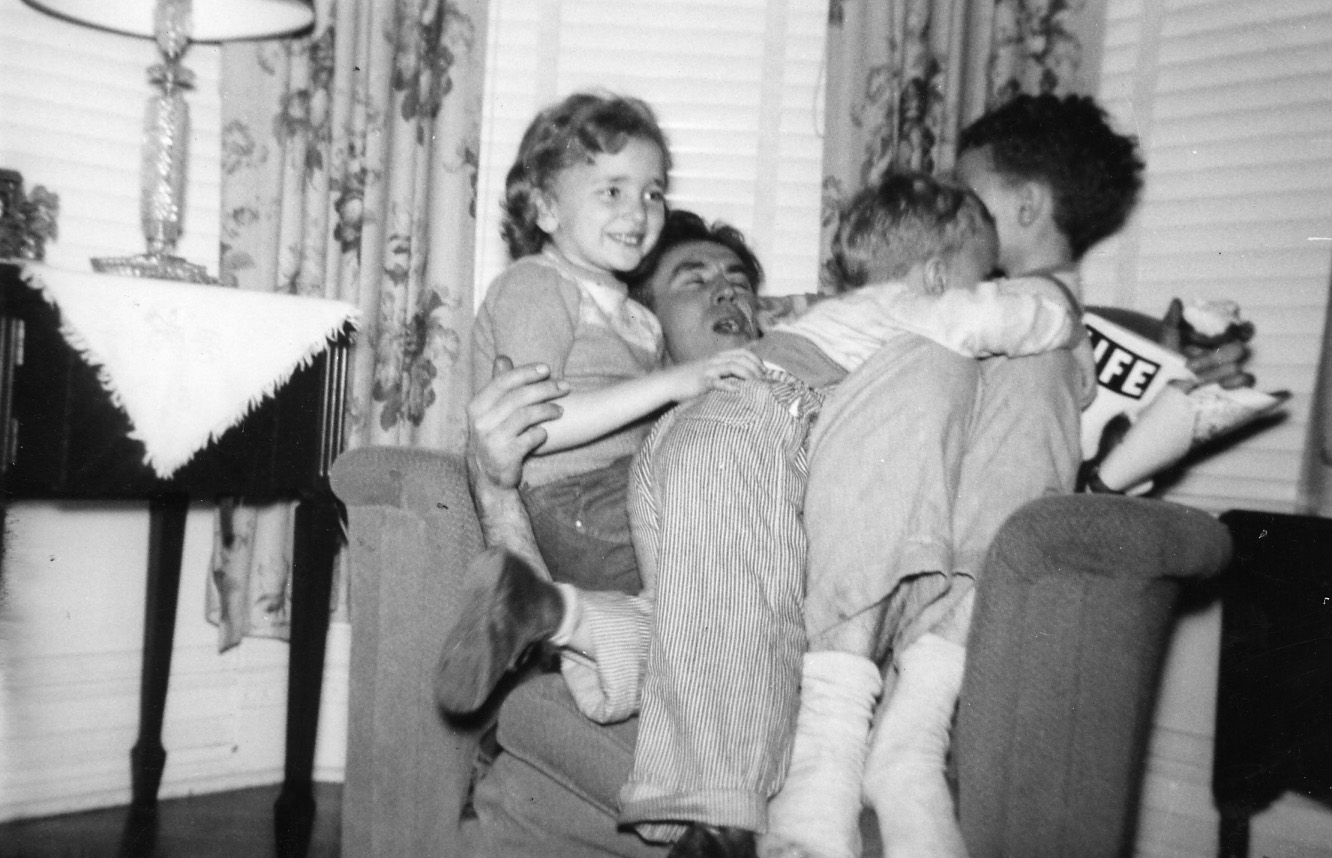

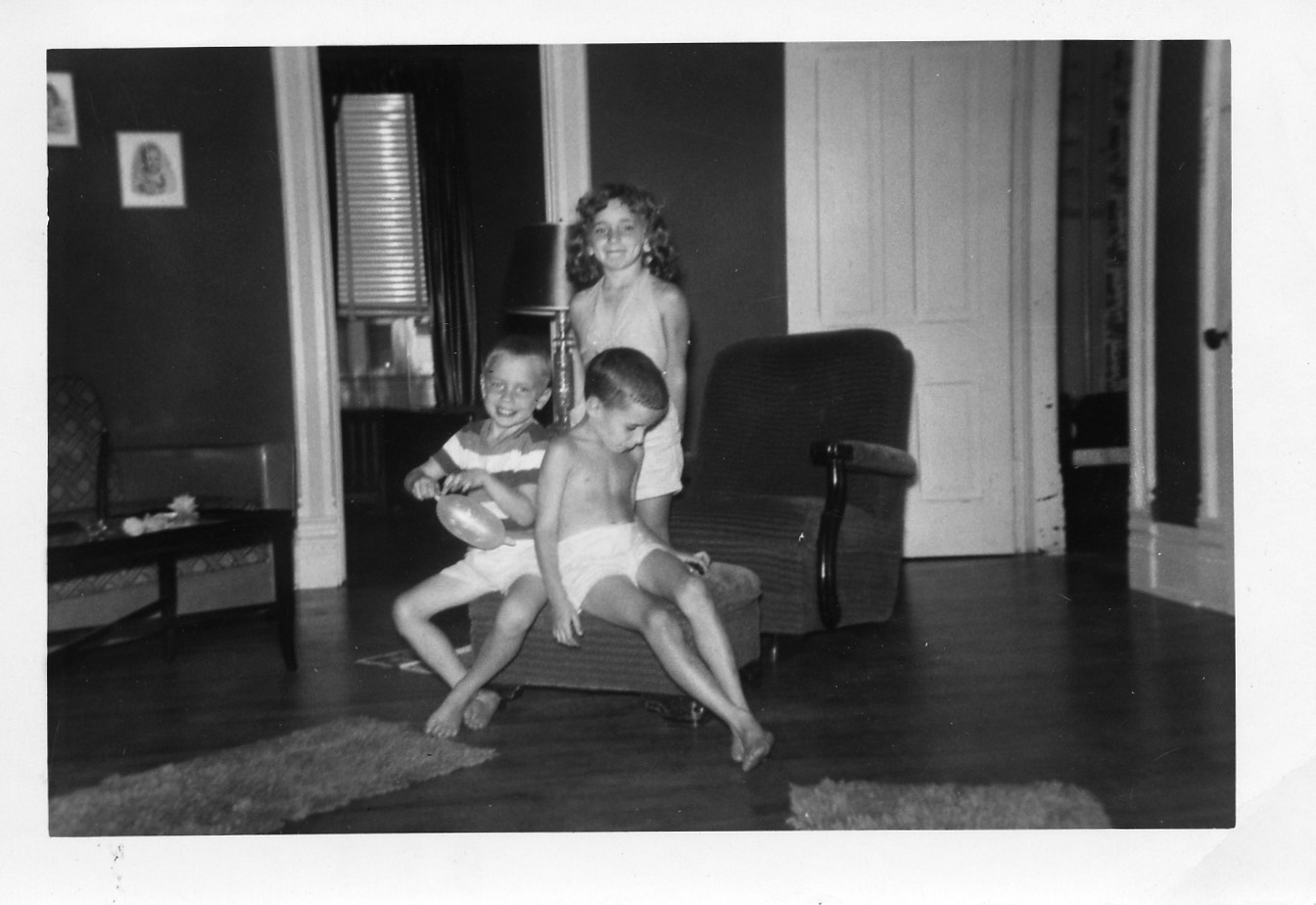

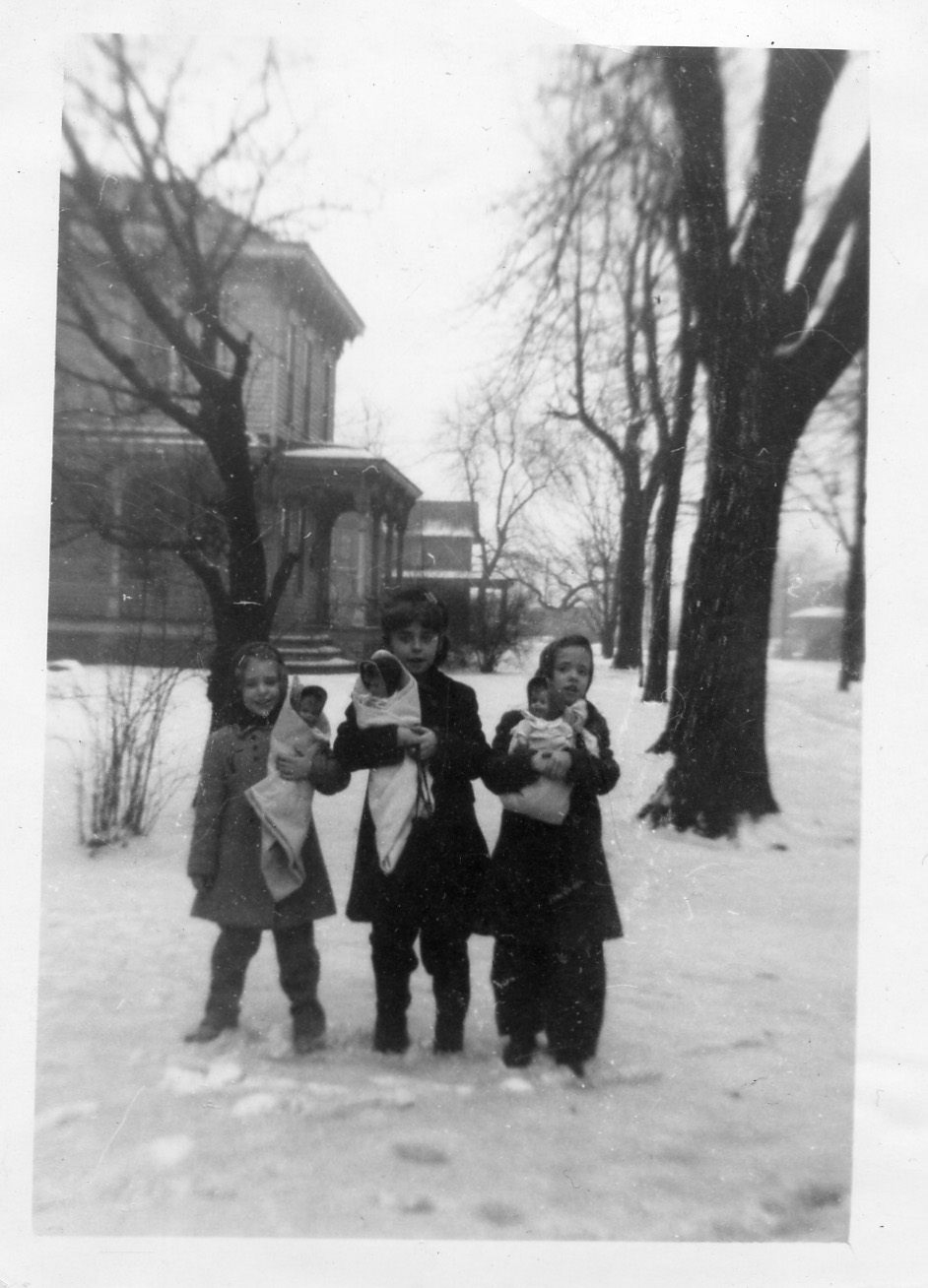

Both of the Wellers worked, so my mom watched the Weller children until their parents returned home in the evenings. So our daytime family consisted of Sandy, Steve, Bob, Christy, Mike, Marla and Rhonda. And our summertime play group often consisted of Sandy, Steve, Bob, Christy, Mike, Marla, Rhonda, Cathy, Connie, Jennifer, Judy and Freddy. We were all part of one gang on the west side of the 600 block of Collett Street. We were very creative in filling our time together. I'm not sure if the Little Rascals influenced us or if the show was just a reflection of the times.

Directly across the street from our house was the home of the Timm's. It was a large yellow house with manicured lawn and beautiful gardens. Most of the children in the neighborhood were afraid of them. When walking on the sidewalk in front of their house, we were careful not to step on their grass, lest they come out the front door screaming. When playing baseball, we would cringe when a fly ball would land on their lawn. One of us would quickly retrieve the ball, running back, never looking behind.

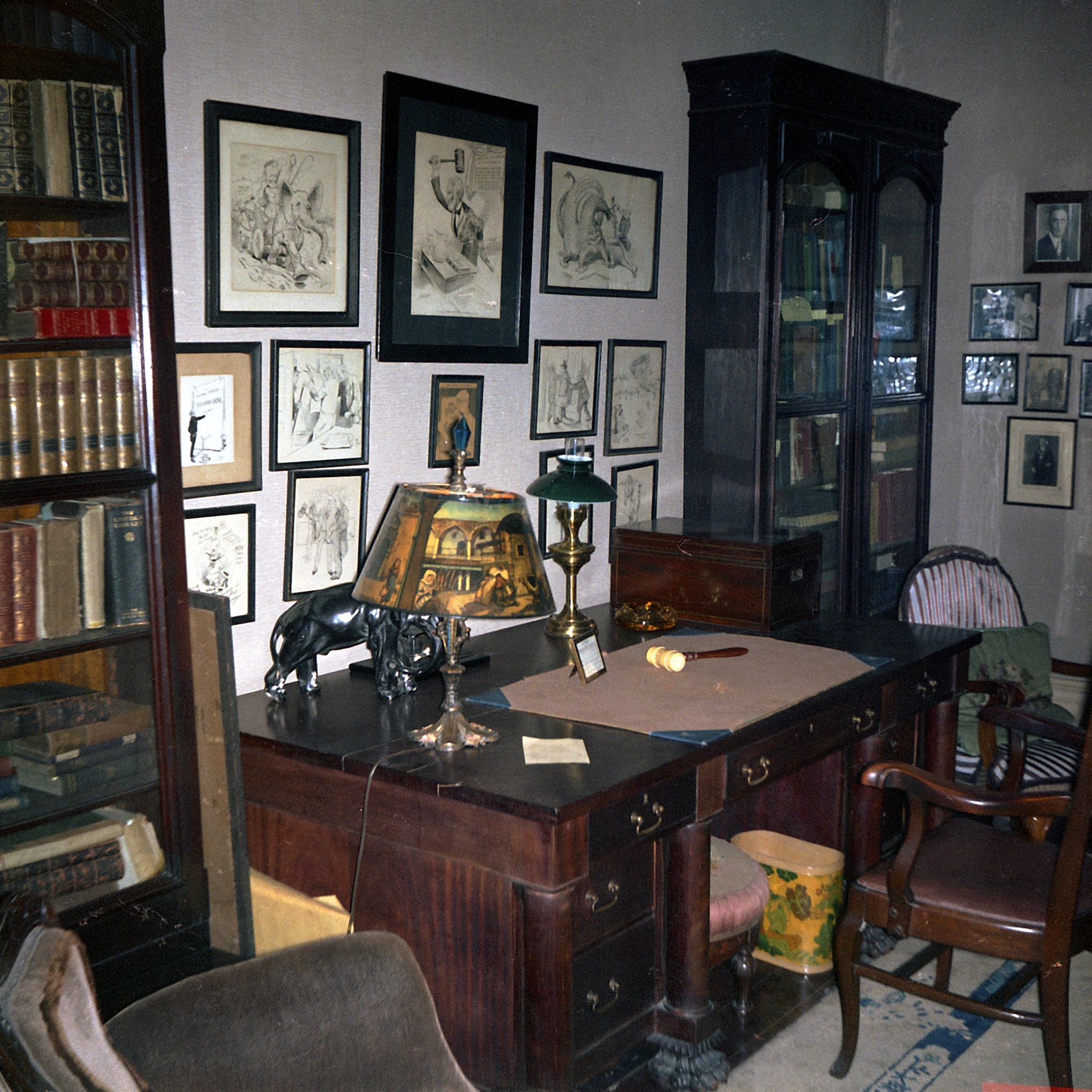

The Timms were shrouded in mystery. Occasionally a delivery truck would park in the driveway. pushing crates of beer down a shoot into the basement. When their granddaughter would visit from St. Louis, a Mercedes would be parked in the driveway. She was a singer and we could hear her practicing songs from the musical Annie Get Your Gun. "Anything you can do I can do better than you." How do I remember all these things, you may ask? When I was 12 years old I started writing things down. I wrote notes to myself for the rest of my life. Those notes are in the attic of the house where I now reside in San Francisco.

On the corner north of the Timm's house was Timm's Grocery. The grocery was owned by a different Timm, a relative. The grocer and butcher was Smitty, a relative of the Roths. The store gave the feeling of stepping into the past. Wooden shelves lined the walls. The wooden floor was worn smooth by decades of boots and shoes. Immediately to the right, upon entering the door was a whole section devoted to children. A large glass case filled with penny candies and candy bars. We would place our pennies on top of the case and point to our choices with our noses pressed upon the glass. Each purchase would be followed with the sound of a manual cash register, ka-ching, followed by a bell that announced the opening of the drawer. In the back, Smitty could be heard chopping meat on a large wooden chopping block.

It was the end of an era. So called progress would eventually destroy all of the institutions that were formed in a world where people were connected to each other by birth, by community and by choice. Now all we can do is count our blessing that we were part of something so intimate and organic.

610 NORTH COLLETT STREET

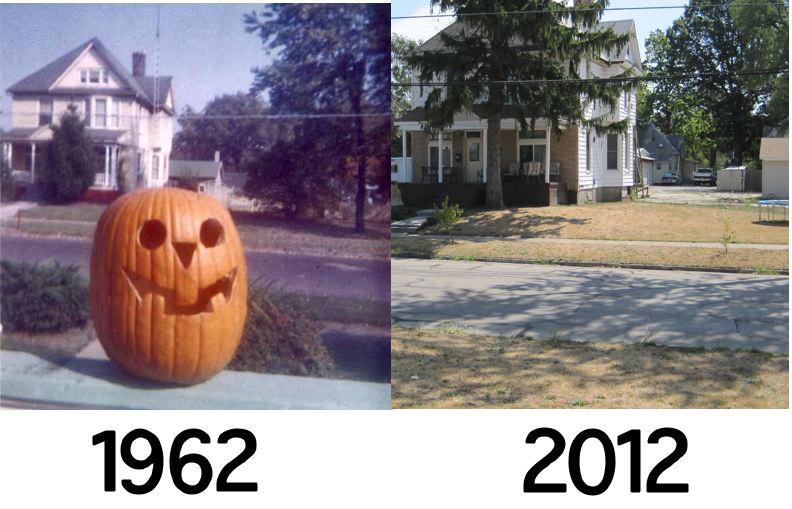

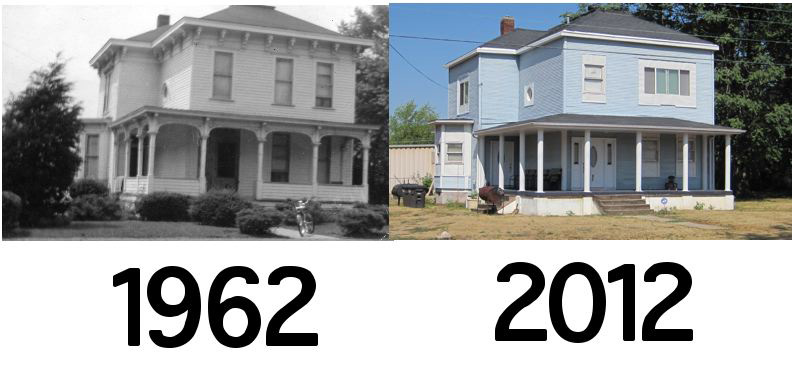

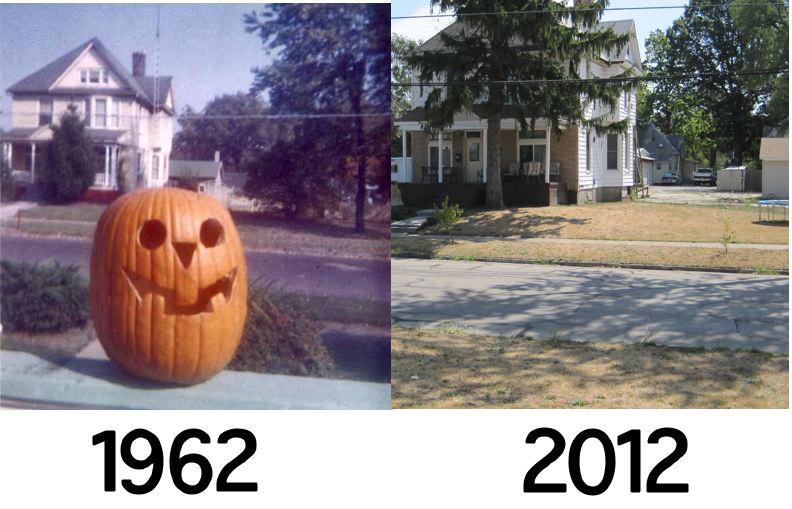

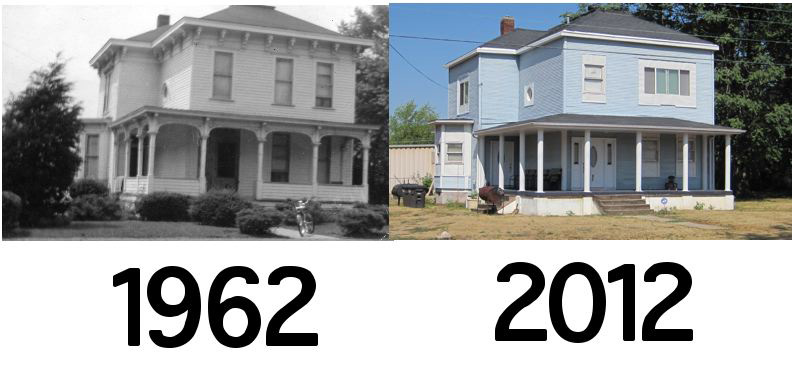

On my last visit to my hometown, Danville, Illinois, I returned to my grandmother's house on Collett Street, where I spent the first twelve years of my life. I introduced myself to the minister who now owned the house where I grew up. He graciously consented to my request to take a photo from the front porch where I had stood fifty years before when I took my very first photograph with a camera that my grandmother had gifted me. The photo was a pumpkin sitting on the railing that no longer existed. In the background was the Timm's house across the street. As I stood on the porch looking out on a multitude of memories, I was astounded by the feeling that i was in the countryside instead of a city. To the north, all the houses had been torn down, along with the memories of all the families who had lives there. I was happy I had written my memories down. Now it's time to resurrect the memories of 610 North Collett Street.

One day my father showed us some original papers and blueprints pertaining to my grandmother's house on Collett Street. I don't remember why he had them on that particular day or where they were put afterwards. I never saw them again. The thing I remember most is that Dan Beckwith was listed on the original deed as the owner of the property in the beginning. My father explained that Dan Beckwith was the Dan in Danville. If I had not seen the papers on that day, I may have never known that part of Danville history. As a matter of fact, I had never imagined that Danville was named after a guy named Dan. It never crossed my mind.

My father and my grandfather worked for Grieser and Son Plumbing and Heating. Together they dug out a new section of the basement for a coal furnace, installing steam radiators on each floor. When my brother Steve and I were old enough, we were given the responsibility of "stoking" the furnace. We were told if we didn't do it right, there was a possibility of blowing up the house. So we were very careful to follow the instructions exactly. The trick was to watch the gauge above the furnace door so the needle never reached the red zone. When the needle got to the appropriate pressure, we were to close the bottom door to stop the air flow that fanned the flames. The bottom door gave access to the ashes which we scooped out with the shovel, depositing them in a large metal bucket to cool. Then the ashes were spread on the alleyway behind the house to create more traction on winter snow. In the summer we kids would be reminded of our furnace jobs as we walked across the ashes in bare feet, wincing in pain.

Next to the furnace room Dad and Grandpa had dug a coal room where truck loads of coal were deposited by chute through a small window. After a load of coal had been delivered, the room was practically filled to the ceiling. On winter mornings everyone remained under the covers in bed until the radiators began to rattle and steam came whistling out of a small valve on the front of each radiator. Sometimes, on the coldest winter nights, we could see frost forming on the walls of our bedroom just before Dad stoked the furnace.

Directly behind the house was a small semi-detached building with a gable roof that we called the summer kitchen. Summer kitchens were common among homes of that era. Our summer kitchen, however, never saw any cooking. It was a repository for my father's tools and fishing supplies. That was how a 19th century necessity was adapted to 20th century uses.

The stairway to the second floor was in a hallway closed off from the first floor by a door from the living room. Under the stairway was a small telephone stand that held our party line telephone. We shared our line with our neighbor, the Roths. Our number was 7974J and the Roth's line was 7974W. If we wanted to make a call, we picked up the phone and waited for the operator to say, "number please."

The stairway had a banister! Yes, the kind of bannister you see kids sliding down in movies and TV sitcoms. You can bet we did just that. But the end of our ride down the shiny polished wooden railing was not as graceful as in the movies. The post at the bottom of the stairs was much too high for a comfortable landing. So we negotiated the ending as best we could. When ever we decided to walk down the stairs like civilized people, we got to fantasize about being on a huge ocean liner. At the top of the stairs a round porthole window was intended to provide natural light to the stairs. But the unintended purpose was to provide a prop for the fantasies of creative children's minds.

In the upstairs bathroom was a small window to provide natural ventilation and light. When I say small, I don't mean tiny. It was big enough for a small body to climb through. Once through the window, that same small body could easily negotiate its way down the graduating roofs to the summer kitchen where a metal pole supporting the back stairway railings could be used like the pole in a fire station.

Just behind the summer kitchen a cherry tree bloomed every spring, providing cherries every June. In the center of the backyard my father had planted a small peach tree that provided peaches a little later in the summer. The lot between our house and the Weller's had plum trees. Walking down the alleyways in summertime, it was understood that anything hanging out over the alley was fair game. So fruits our own trees did not provide were accessible in the rest of the neighborhood.

On certain days of the week the iceman came to provide a huge block of ice to the Timms for their icebox. As the cold sharp, shiny metal fingers of the ice tongs crashed into the block of ice, pieces of ice fell onto the brick pavement. They were exactly the right size for cooling off children playing on a hot summer day in the nearby field. We simply brushed aside the dirt and started sucking on the ice like it was a lollypop. Later in the afternoon the ice cream man would park his truck in the same place the ice man had been in the morning. The music box type jingle worked like a Pavlovian dog clicker. We all lined up as a man in a white hat bent down to dispense ice cream and popsicles through a small window. The window was definitely designed for our convenience, not his.

My grandmother's house was situated on a street where during more than a decade up to eighteen children had grown up in the same block, on the same side of the street. We were all part of a family that was bigger than our biological families. By playing together we learned together. We broke down barriers and planted seeds that would inform our future decisions in life. We had taken the first step of socializing outside the boundaries of our biological, religious and cultural teachings. While we were having fun, we unwittingly prepared ourselves for interacting in a bigger world.

CUTTING THE APRON STRINGS

My bicycle was the chosen mode of transportation for my first escape from the very well defined perimeters my parents had imposed on me. Each time I expanded the boundaries, my mind was also being expanded. Little by little I clipped the apron strings as I came to understand that I had the capability to make decisions for myself. Sometimes I wondered if perhaps my mom and dad were standing in the wings cheering me on, because personal freedom and responsibility were exactly what they were preparing me for. My mom would always joke: “When you leave I’m selling your bed so you can’t come back!” Of course there were always beds in the spare bedrooms whenever any of us wanted to come home.

The first time I rode the Illini-Swallow bus to the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana, I cut the apron strings forever. It was like a dream come true, as if someone had constructed a pipeline from Chicago, that ran beneath all the rural farm lands, then suddenly exploded onto the University of Illinois campus. When I attended my first event at the Student Union Building, I imagined I was attaching my brain to a million tentacles that led to a million places and ideas I had yet to explore. No longer was my concept of the outside world defined by buying the next copy of the Sunday New York Times from the newsstand at the Plaza Hotel. Now I was able to talk to people who actually grew up in the places I dreamt of visiting. I learned that Chinese food was much more than Chop Suey and plastic noodles. I tasted sushi with wasabi for the first time. I ate my first bagel with lox and cream cheese.

I rode the Illini-Swallow lines back and forth between Champaign and Danville many times before it occurred to me that I could ride the same bus in the opposite direction and be in Indianapolis, a bigger city than CU with different lessons to be learned. My hometown was strategically located between two sources of infinite learning. I was hooked. It was like that WW2 song I had heard my mother sing. “How you gonna keep’em down on the farm, after they’ve seen Paris?“ When I brought little pieces of my “Paris” back to Danville, it only strengthened my position as a weird boy who was very different.

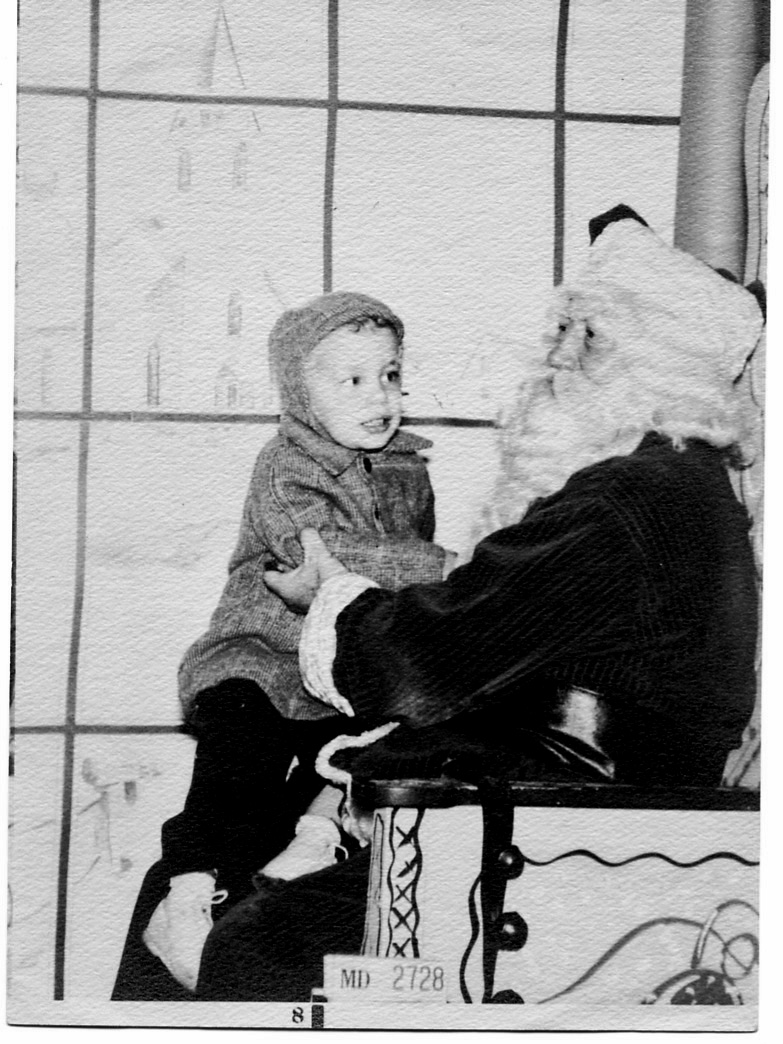

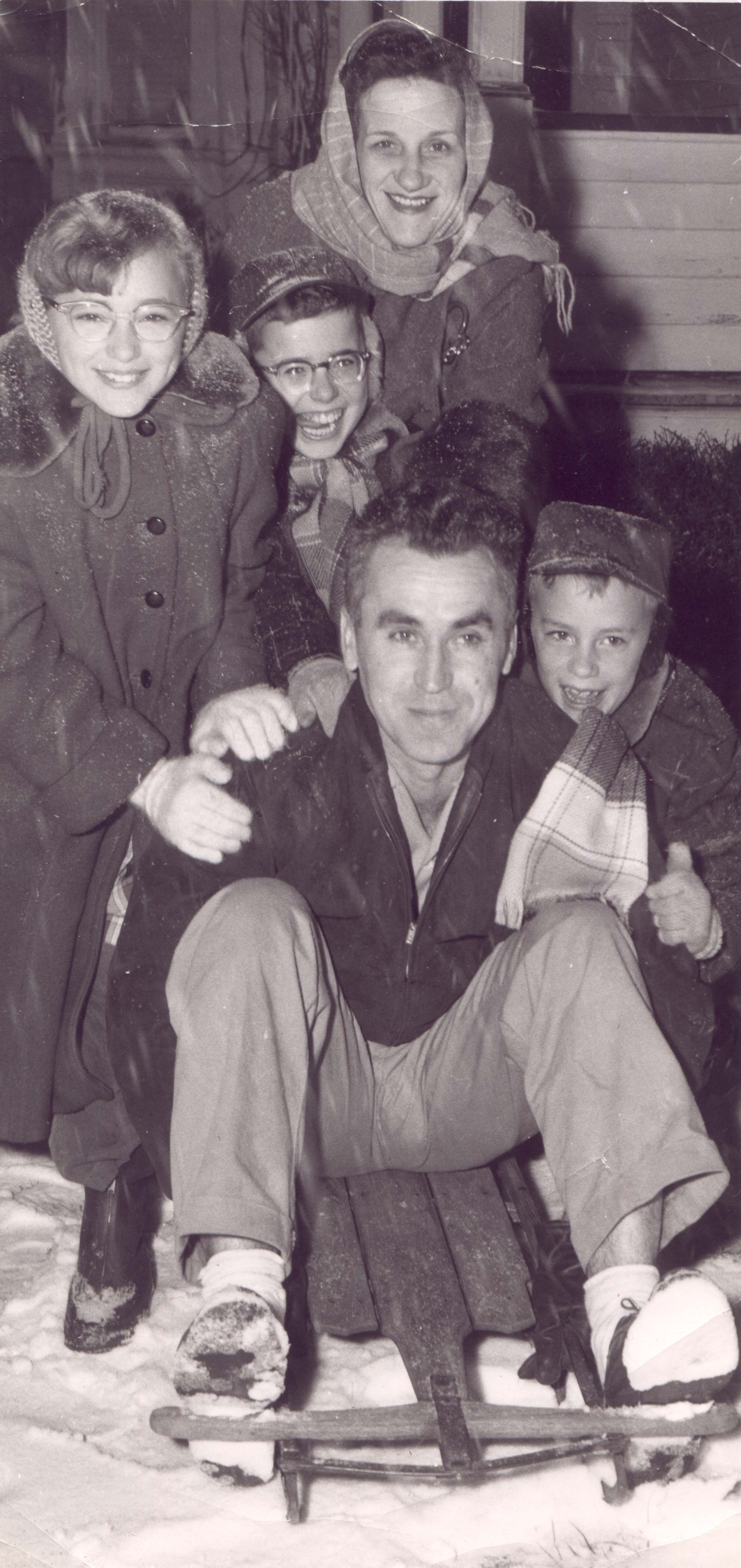

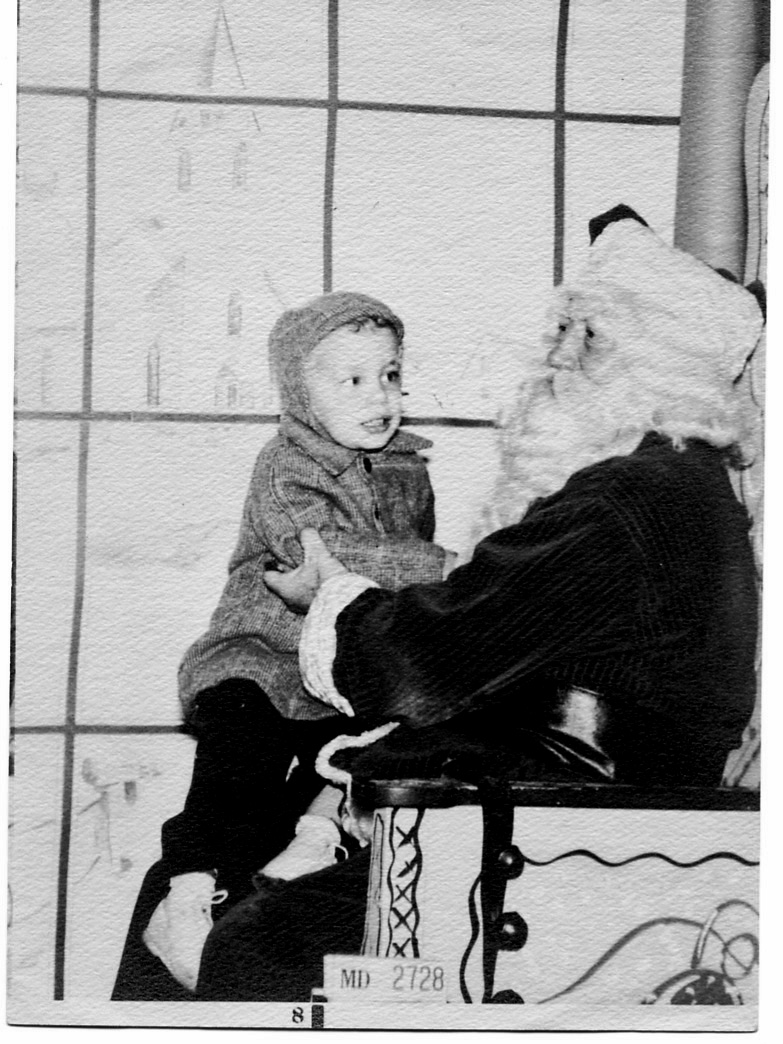

CHRISTMAS

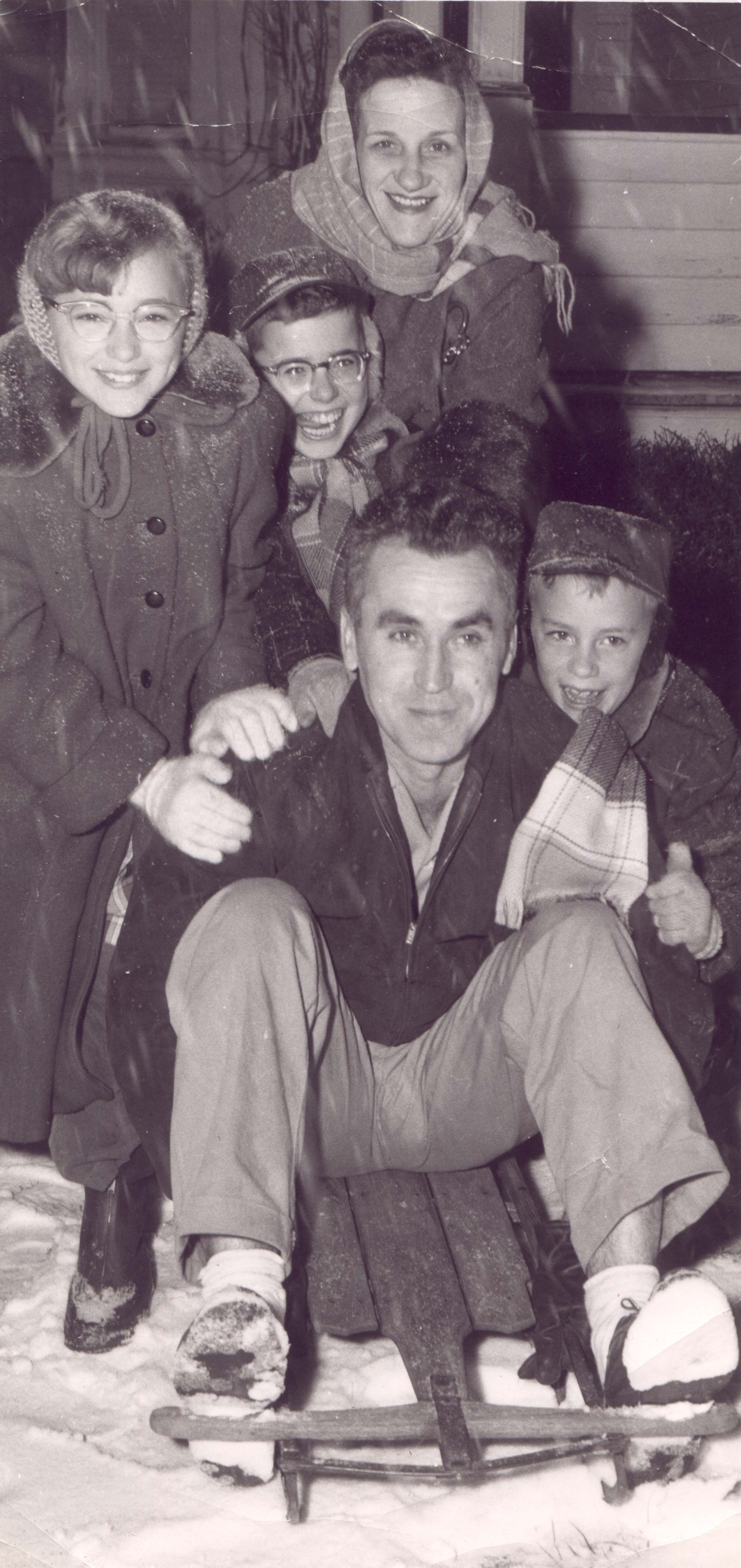

I believe Bing Crosby is responsible for much of our obsession with having a White Christmas. But the conversations among children always revolved around whether there was enough snow for Santa’s sleigh. I spent more than one Christmas eve night lying in bed listening for sleigh bells. I also recall a Christmas day when the temperature reached into the sixties and everyone brought their new toys outside to play. But most Christmases were cold and many were white. One Christmas day was spent spinning down the hill above the small pond next to Lakeview Hospital on our new fiber glass flying saucer sled. When two boys fell through the ice, my father was first on the scene and he too fell through the ice trying to save the boys. Everyone got out safely, but very wet and cold.

Christmas at our house began in November when my mother would make fruit cakes and German springerle rolling pin cookies. The cookies were put in tins and the fruit cakes were wrapped in dishtowels soaked with rum. My mother said they were kept in the pantry until Christmas because they needed to age properly, like wine. My mother’s baking and cooking were very important parts of the Christmas memories we would carry throughout our lives.

A few weeks before Christmas we would form an assembly line to create the Santa cookies with raisin eyes, red sugar lips and coconut beards. The smell of cinnamon rolls baking on Christmas morning would almost succeed in distracting us from our main goal of unwrapping our gifts. In mother’s large crockery bowl, bread dough would rise up under the damp dish towel covering the bowl, only to be kneaded down to rise two more times. Later Mom would carefully divide the dough into small balls placing three in each muffin tin to create cloverleaf rolls. The aroma of fresh baking bread was an important element in the sweet and savory Christmas bouquet.

Decorating the Christmas tree was always a family event. Dad had the honor of stringing the lights, which were large colored bulbs back then. The floor was strewn with open soft cardboard ornament boxes waiting to be unpacked. Mom would continually remind us to put the tinsel on one strand at a time. Occasionally we would walk to the other side of the room, squint our eyes like an artist contemplating a painting, then return to fill in the dead spots. In the background, on our black and white Emerson TV that had been moved to the left to make room for the tree, we would hear Alastair Sim proclaim “Bah, humbug!” Or Jimmy Stewart (George) telling Mary one more time that he’ll lasso the moon for her. And through it all was the ever present fragrance of a freshly cut pine, the essence of Christmas.

Christmas was so special to children, we would use the phrase “just like Christmas,” in later life to describe an event that is very enjoyable. But the truth is, nothing in later life could ever come close to Christmas as a child. On Christmas morning our eyes were open the moment the first ray of daylight snuck between the slats of the Venetian blinds. We were sentenced to remain in bed until we heard the clanging of the radiators announcing the arrival of heat. Someone would come to the door to give the all clear to assemble in the living room. Then we sat in a semicircle waiting for Mom to pick up the gifts one at a time, reading the labels aloud, then distributing them to their rightful owners. This created absolute carnage as we totally disregarded the time and effort put into wrapping the packages and tying the bows. We ripped the paper and bows apart like hungry dogs tearing meat from bones. Just before breakfast we would carry our spoils back to the bedroom where we would display our gifts neatly on our beds as Mom picked up the garbage off the living room floor.

Fast forward thirty years to the future. My Christmases in Germany and Austria were very different. Christmas trees were purchased and decorated on Christmas Eve. Real candles were lit on the branches of the tree. Everyone was given one thoughtful simple gift from each person. During December, in the center of each village or town was a Christkindlmarkt, (Christmas Market), selling Christmas ornaments, Christmas cookies and Glühwein, (hot mulled wine). Christmas in Germany was more of a spiritual event and less about gifts. Gee, now it’s hard for me to say which was better, the Christmases of my childhood or the Christmases of my travels. Let’s call it a draw and end it there.

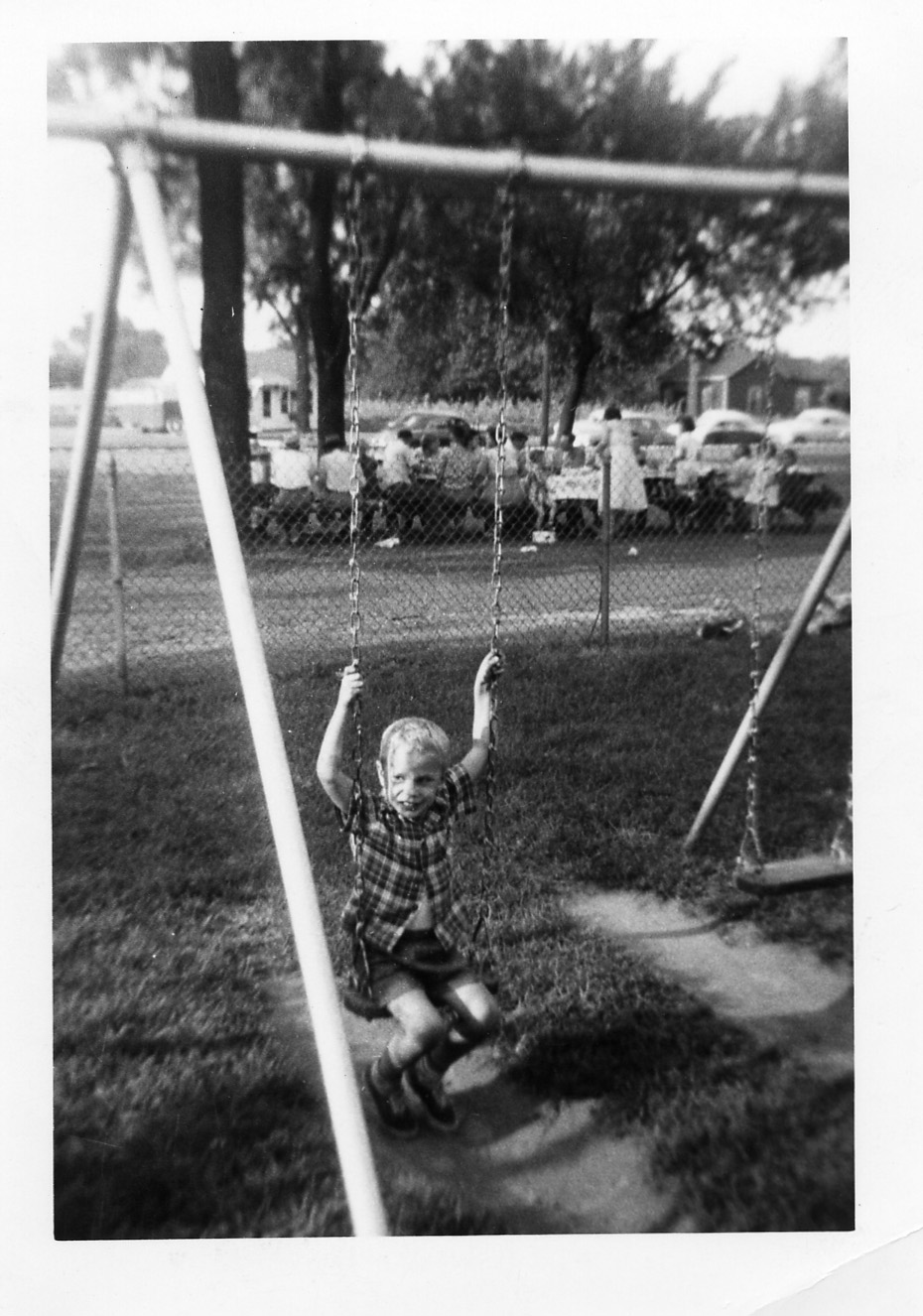

DOUGLAS PARK

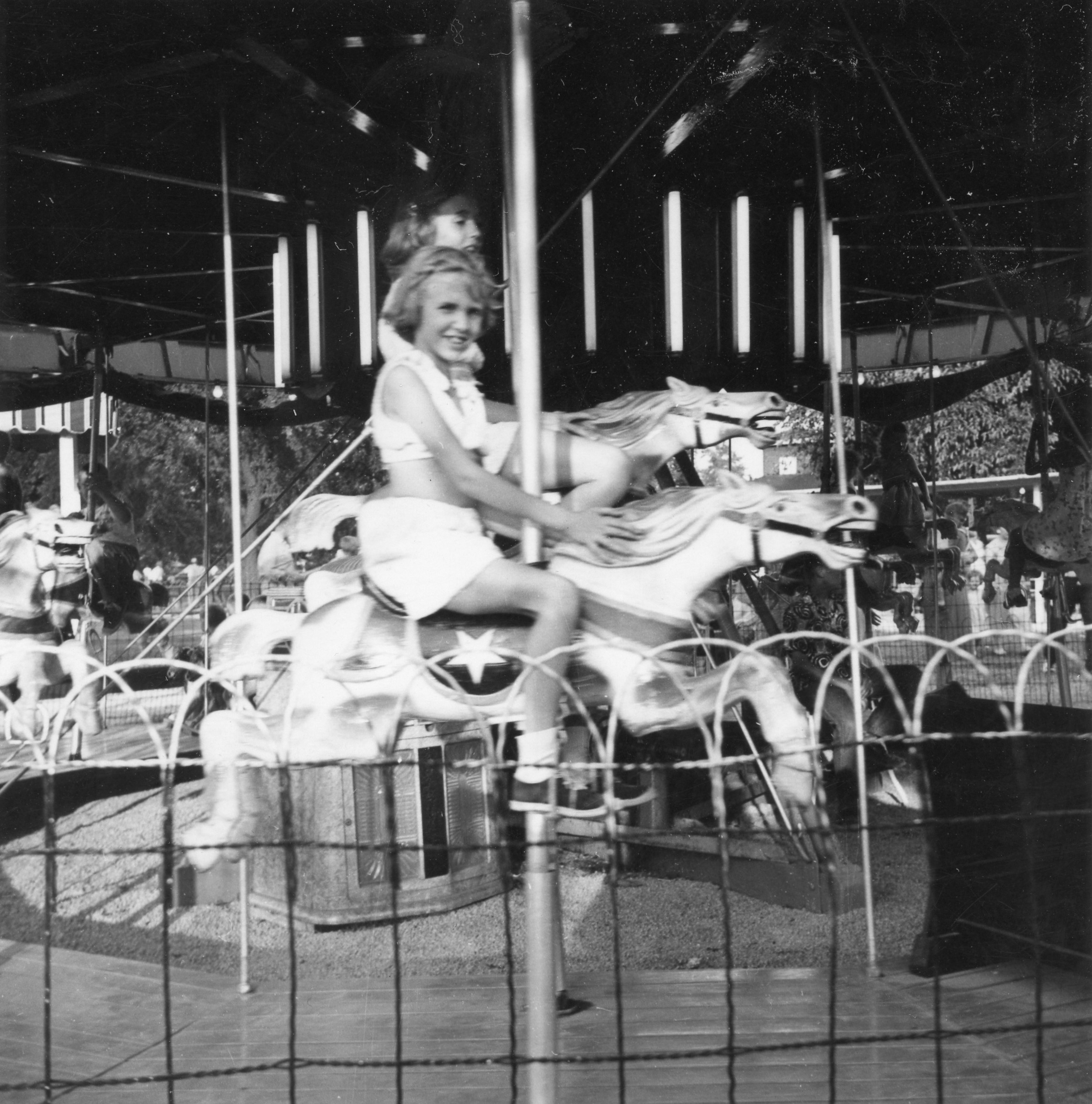

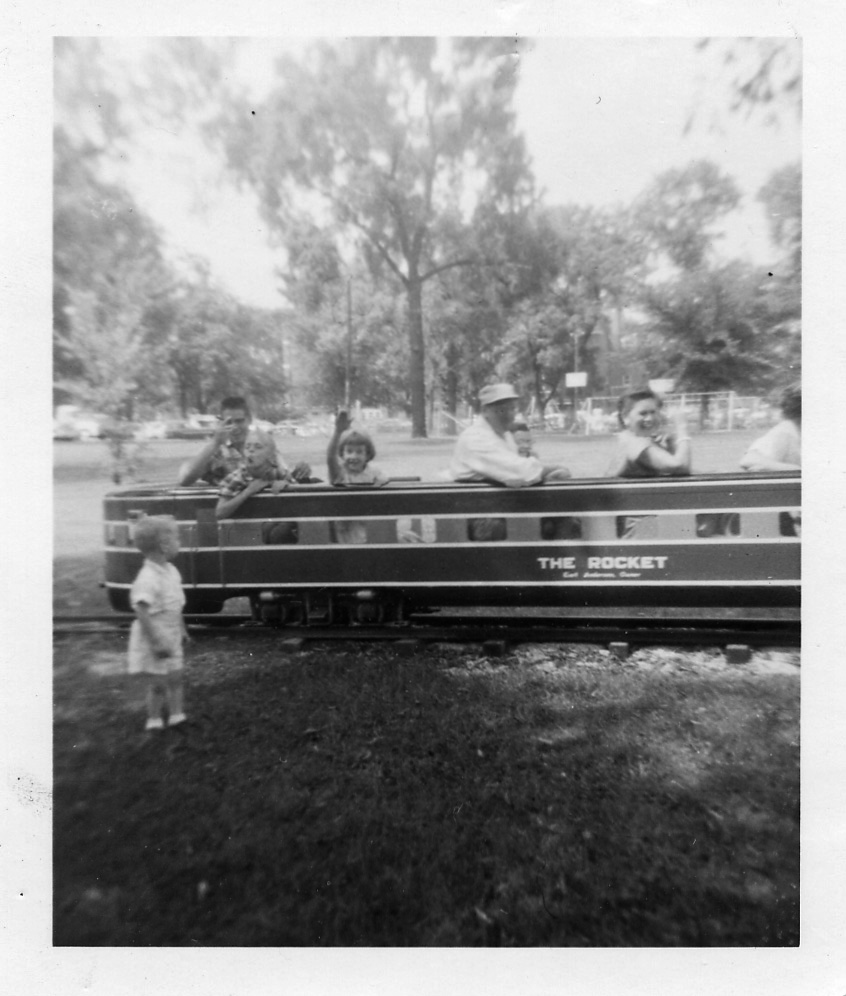

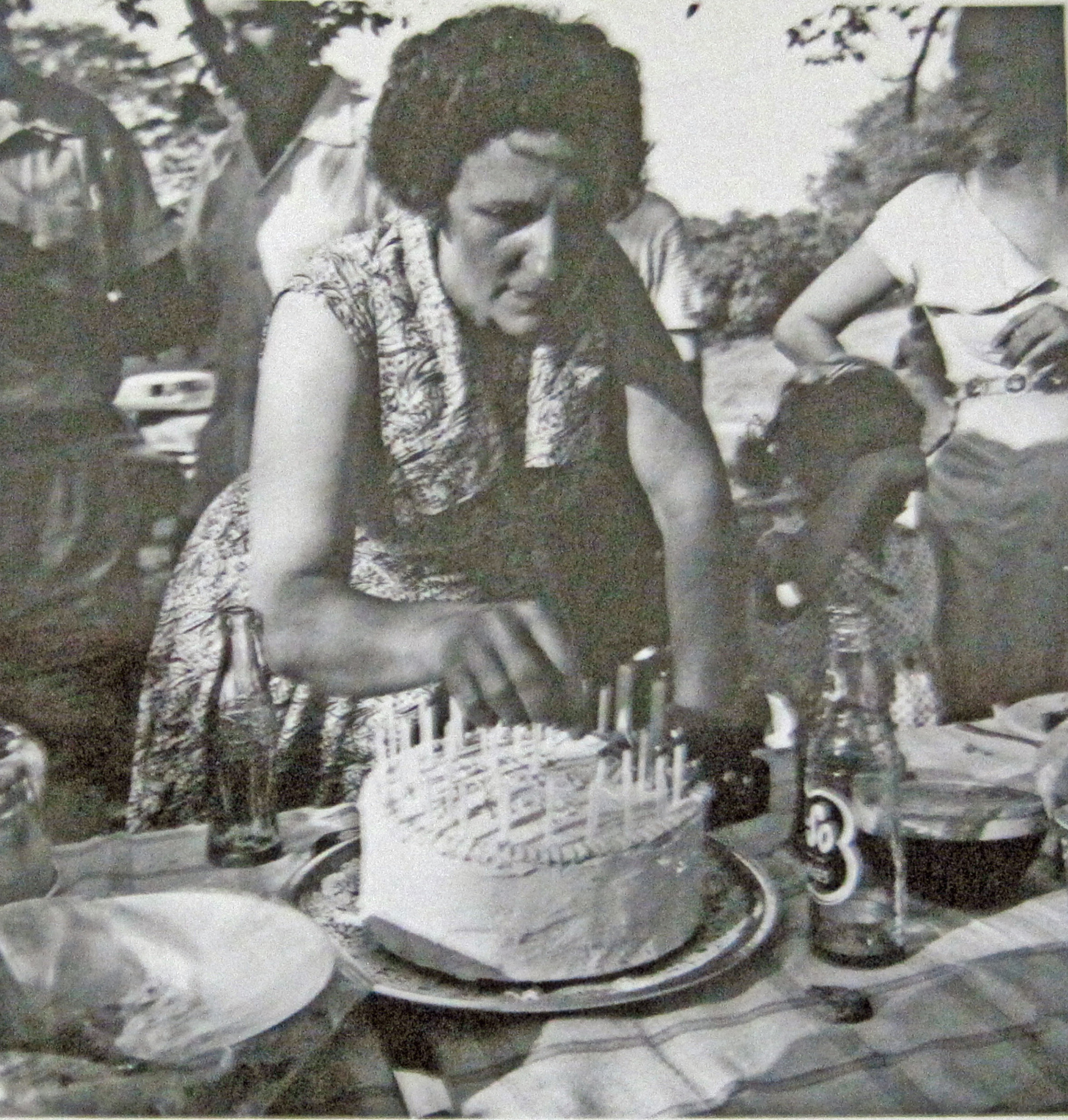

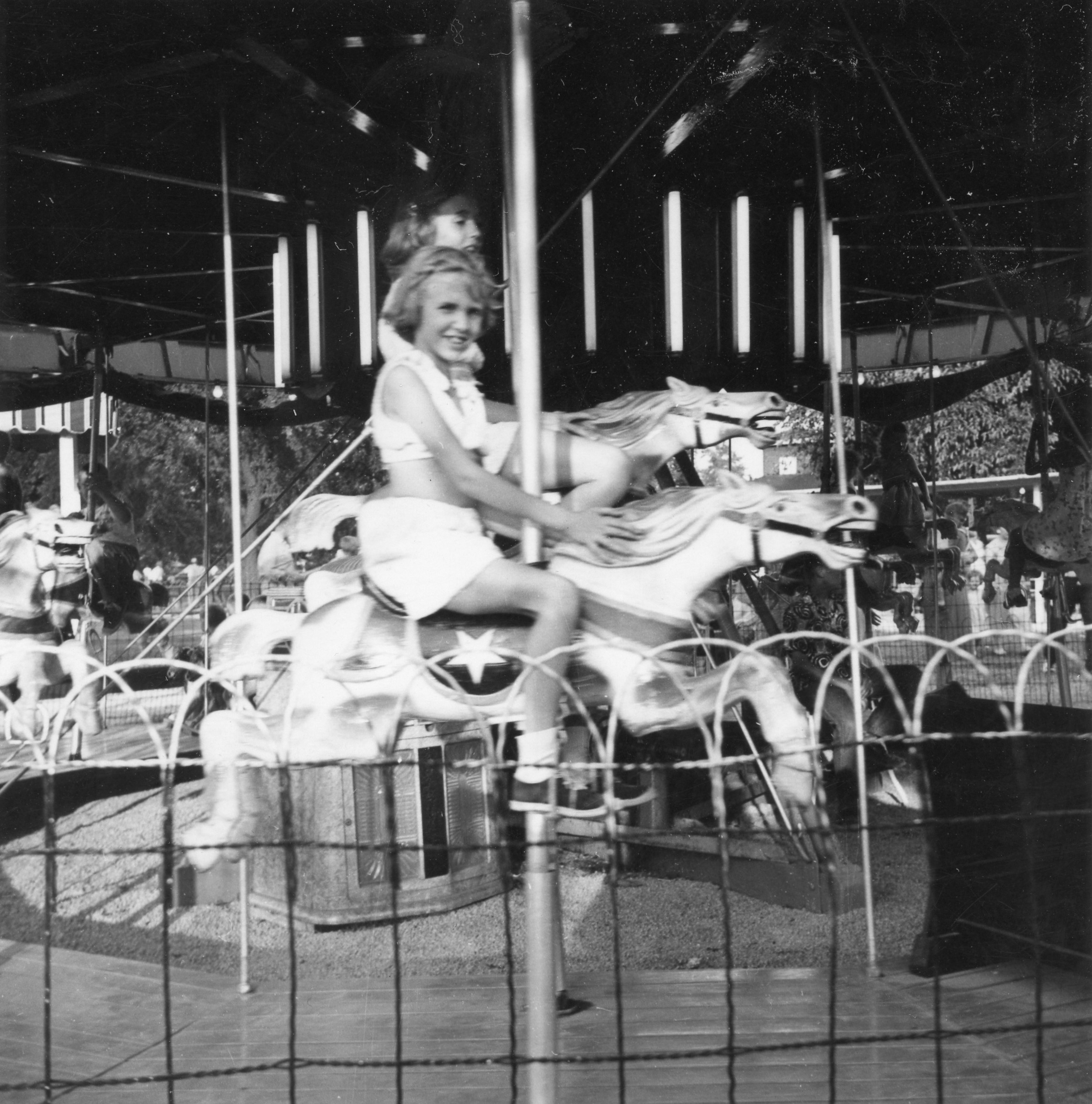

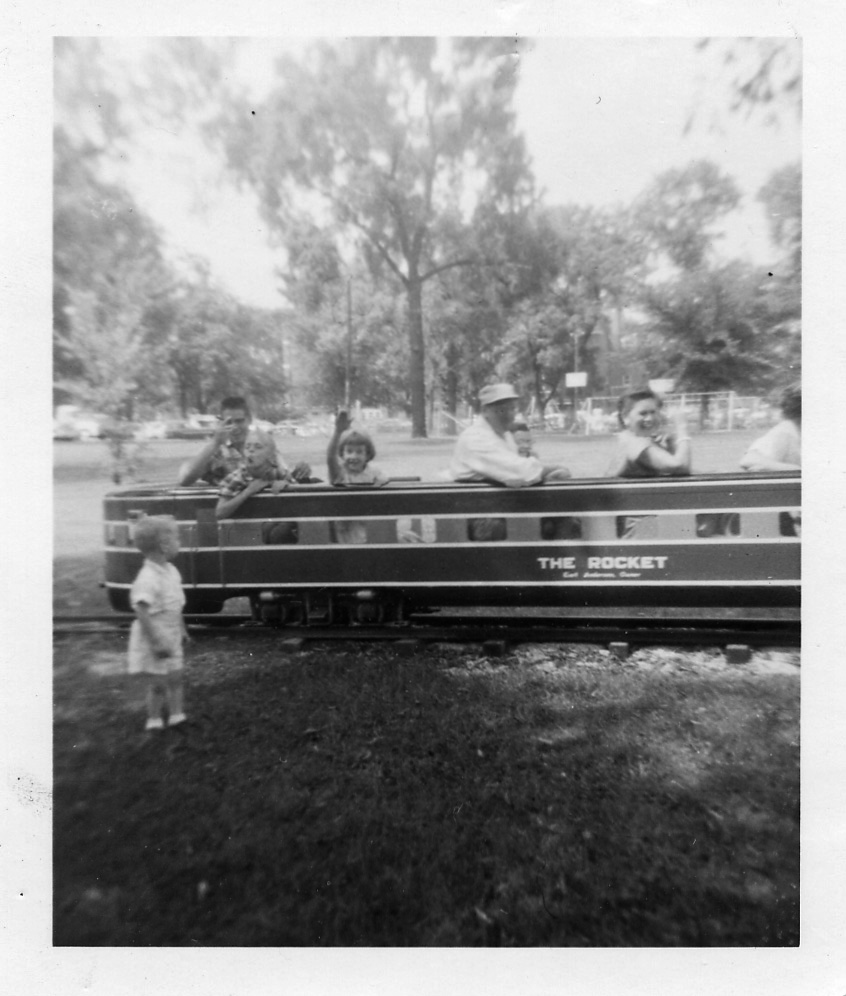

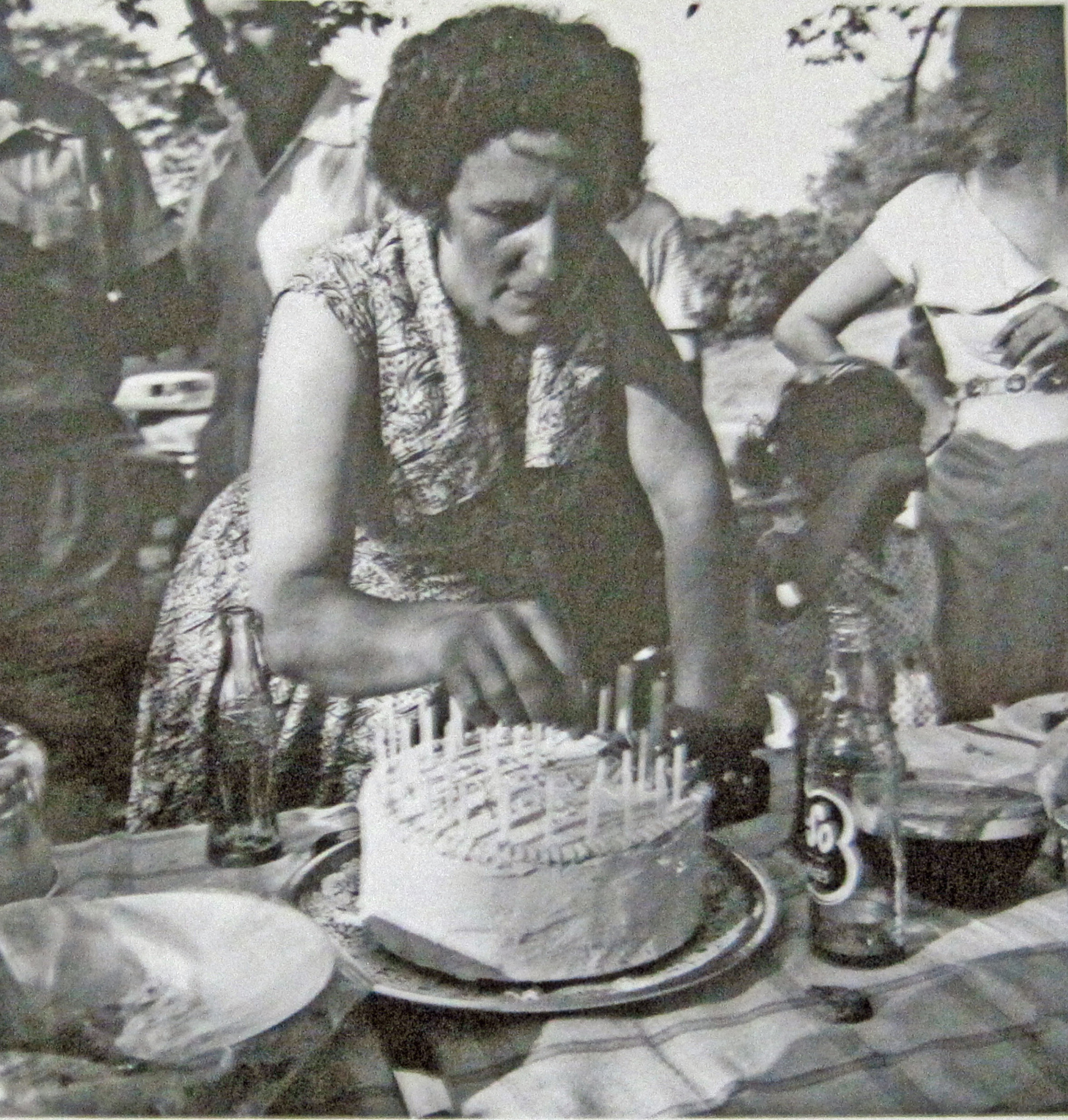

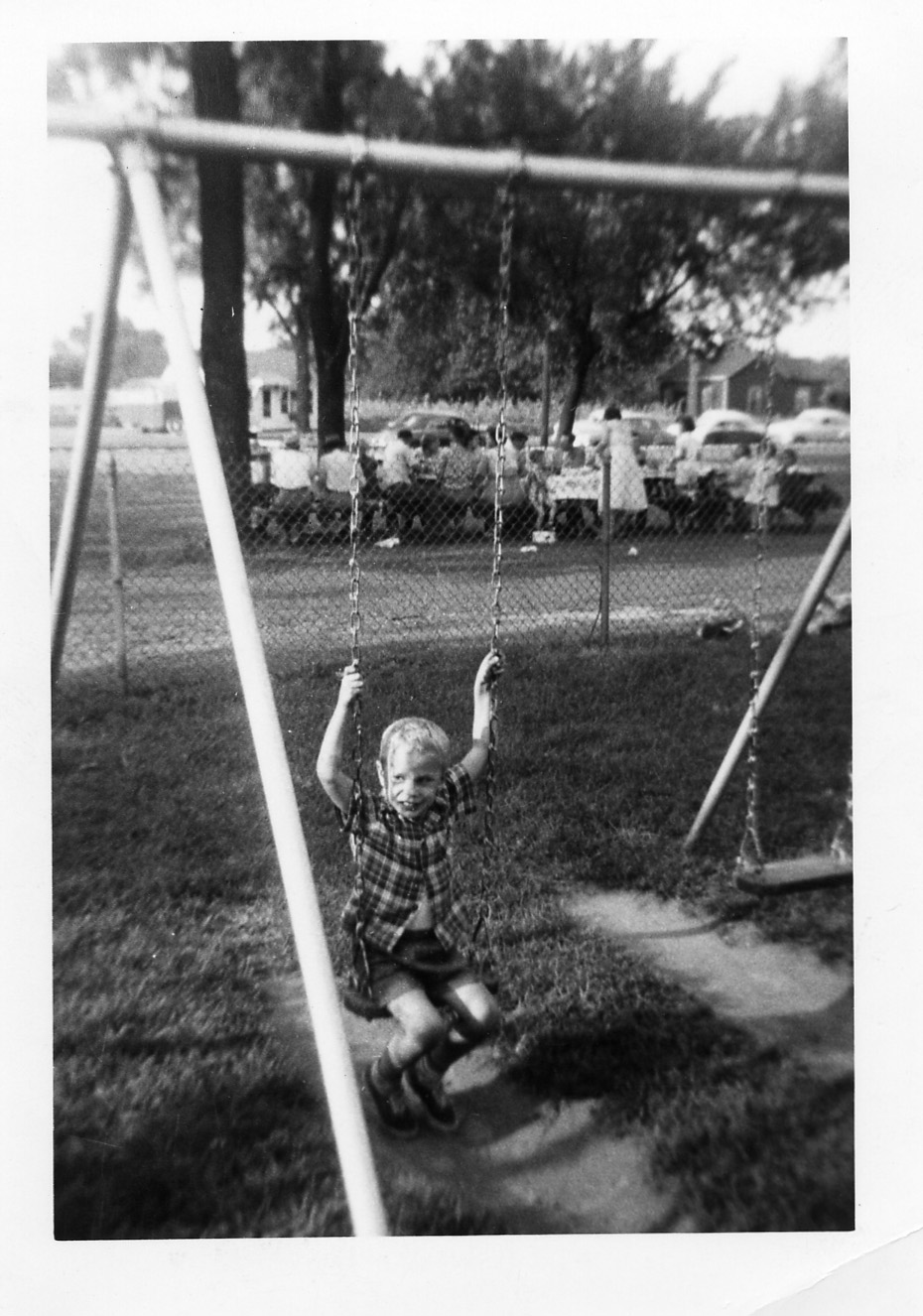

Search through any photo album of Danville, Illinois residents from the second half of the twentieth century and you are bound to find pictures of Douglas Park. This was the summer weekend go to place for many family reunions or just a spur of the moment picnic. Douglas Park was the favorite of children because there was a merry-go-round, a train, a roller-coaster, bumper cars, and boats.

If I close my eyes, I smell the aroma of fried chicken, the taste of potato salad, the feel of cold strawberry snow cones, a fleeting moment of candy cotton as it magically disappears on the tongue. In the background I hear the squeaking of the coaster brakes followed by the sound of the chain that drags the cars to the top of the hill. The cars are released as the passengers throw their hands up in the air and scream with joy until they reach the bottom of the hill.

I hear the sound of ice swooshing through cold water inside the huge metal tub that holds glass bottles of “pop.” The crunchy salty flavor of potato chips dipped in sour cream onion dip. The unique texture and flavor of red and black licorice whips. The sound of wood upon wood as a croquet mallet comes in contact with a croquet ball. A baseball game broadcast upon the newly invented transistor radio can be heard as uncles and cousins gather at a nearby picnic table to cheer on their favorite team. This is a place I go in my mind to remember how it felt to feel totally protected, at peace and so happy it was impossible to contain my laughter.

THEATERS

I don’t remember if it was the Fisher Theater or the Palace Theater, but it was definitely a Saturday morning. The theater was filled with screaming children, including myself. I remember lots of cartoons. Then there was an auction of sorts, where the currency consisted of cut out waxy labels from milk cartons. That’s probably the earliest memory I have of going to a theater.

Mom and Dad took us to see the movie Giant. That’s my only memory of actually sitting in a theater with my parents beside me. Of course, like any 1950s American family, we went to the drive-in together. Usually on a hot summer night when no one wanted to be inside a house. They would send us kids up to the concession stand during the movie to avoid the crowds at intermission.

I have two memories of going to the movies with my sister Chris. The first was to see a matinee rerun of the horror movie “The Blob.” I don’t think Chris slept for a week after that. The second was The Beatles, “Yellow Submarine.” And many cartoon Saturdays with big brother Bobby.

At one point I had decided to graduate from the profession of neighborhood grass cutter, to take on the task of a theater usher. I arrived early on my first day so they could show me the ropes. I lasted about two hours before I quit. Opening the door to the room in the basement where the already popped popcorn was stashed in big plastic bags, I saw rats scurrying into the four corners. I never ate popcorn in a theater again, unless it was popped fresh behind the counter before my very eyes.

Of course I was there for the opening of Mary Poppins in 1964. But those theaters of my youth also allowed me to grow beyond the boundaries of the landlocked midwest. As I watched “The Sound Of Music,” I imagined that I would one day stroll through those hills near Salzburg, and I did. After standing on the set of “Thoroughly Modern Millie” on my first trip to California in 1967, I came back to Danville to actually watch the movie on the big screen. “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner” would become one of my all time favorites because I identified with it so personally. “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” would inspire a rebellious part of my being that longed to jump off a cliff with absolute confidence that everything would turn out okay. “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis” and “Fiddler on the Roof,” stoked a curiosity of the world that I have yet to satisfy.

Movie theaters were important because they were the link between the era of radio and television. In 1927, sound was added to movies, revolutionizing communications. Then color was added to movies as symbolized in “The Wizard of Oz.” In the 1950s, visuals were added to the sound of radio in the form of television. But in my lifetime, with all the advancements in communications technology, there is still nothing more special than sitting in the audience of a vintage theater, with a bag of (freshly popped) popcorn, watching a movie on the big screen.

TRAIN OF THOUGHT

One of my favorite things as a child was riding the bus downtown with my grandmother. We lived at the end of the line and waited for the bus in front of Mrs. Bowman's house, a friend of my grandmother. Mrs. Bowman had a huge lot beside her house with an apple tree. The lot was divided by a path worn by people cutting through as a shortcut.

I cannot speak of Mrs. Bowman's lot without mentioning the day the circus came to town. The circus unloaded their train where the tracks intersected E. Williams Street, two blocks from our bus stop. All the neighbors congregated in Mrs. Bowman's lot as we watched elephants, clowns and acrobats dancing down the middle of E. Williams Street on their way to the fairgrounds.

But getting back to my trip downtown with Grandma. We always had lunch at the counter in Woolworths. I always ordered a cherry coke, club sandwich and potato salad. After lunch we would browse the shelves of the 5 & dime. I was always sure to go home with some small souvenir of our trip.

The elegant interior of the 1950s bus is etched in my mind. Everytime I get on a refurbished streetcar in San Francisco, I am reminded of my trips with my grandmother in the late 1950s.

YOUTH

When I see the word youth I am reminded of George Bernard Shaw’s quote, “Youth is wasted on the young.” As a senior citizen, I fully understand the meaning of his quote. But I have to ask myself, if it’s wasted, why do we all go back to the memories of those days to satisfy our lust for youth? If we were able to physically go back as adults, wouldn’t we screw everything up the way we already have? Perhaps a more fitting quote might be: “adulthood is wasted on adults.” Perhaps what we really want is a more achievable goal of getting in touch with our inner child.

When I close my eyes I always see myself standing on the red brick sidewalk in front of my grandmother’s house on Collett Street. If I stand facing south, I imagine all the times I walked to and from Collett School alone. I remember coming home from a grocery shopping trip at Eisner’s supermarket on Vermilion Street to find friends of my mother seated in the kitchen with a pot of coffee and donuts. We never locked our doors. Mom always had dinner on the table at exactly four o’clock. I never had to worry about anything, because that was the job of the adults in my life. Perhaps it’s a return to that feeling of security we long for.

So much of the world is new to young people, They are not jaded from a feeling that they have already been everywhere and done everything. If we think about it, children are really easy to please. For instance, a ride up North Vermilion Street to The Custard Cup for the most delicious ice cream on earth was always a crowd pleaser. Afterwards we would cruise further up Vermilion to the entrance to the cemetery where we watched swans gracefully gliding back and forth on the pond. Other great North Vermilion attractions included the giant Indian and Tin Man towering over the passing traffic, to the delight of children.

I remember summer trips to the Sportsman’s Club for family reunions. Cruising slowly up Vermilion looking for that elusive turn off to the left. The smell of hamburgers and hot dogs grilling. Cousins racing by on water skis.

We also made trips to Liberty Market, where they “plugged” watermelons to be sure they were ripe. The Putt Putt miniature golf course was always fun! In the fall, Coates orchard provided bushels of apples in huge wicker baskets. The A&W root beer stand had the best hot dogs, tamales wrapped in corn husks, and Brown Cows (Root Beer Floats) served on trays that hung from a half opened car window.

>From the perspective of a child North Vermilion Street was our Avenue des Champs-Élysées. As children, we were not aware of how much of our happiness was due to our parents attempts to make us happy. Think about it. Our happiness depended on the adults who had charge over our lives. We are all adults now. Perhaps it’s time we took charge of our lives and made ourselves happy.

Anybody wanna go to the Custard Cup?

DOWNTOWN

The door to Walgreens was not on Vermilion or North Streets. It faced northeast. That small corner cut-out made it the perfect place to stand when waiting for a ride to arrive on either street, especially in winter or on rainy days. Just inside the door was a convenient pay phone for calling cabs. One half block east, on North street was the Prescription Shop, a smaller local pharmacy with loyal customers for decades, including my mother. Their personalized service and first name basis allowed them to overcome the trend to the Walgreens of the world. Directly across the street on the same side of Vermilion Street was Montgomery Ward, and one half block north stood Sears and Roebuck.

This was before the concept of shopping malls. In the 1950s nobody imagined a controlled environment where people could walk back and forth between stores without getting cold or wet. We ran during rain storms, bundled up during cold winters, wore shorts and T-shirts in summer and sweaters in spring and fall. You can’t want what you don’t know. So we trudged along, accepting the seasons with little complaint.

The most exciting time in downtown Danville, was of course Christmas. There was a steady stream of shoppers filling the sidewalks on the path that began at Meis Brothers on west Main Street, ending at Sears on Vermilion. Meis Brothers had an animated Christmas display in the front window each year, perhaps inspired by movies like Miracle On 34th Street. During bad weather my mom would always take us on a shortcut through the lobby of the court house from Main to Vermilion. The shopper’s parade on Vermilion began with the two “dime stores’ Woolworths and S S Kresge that provided the best stocking stuffers. Then a hop across the street to Osco Drugs to buy wrapping paper and tape. Then the last two stops, Montgomery Ward and Sears, where you could, of course, find just about everything.

I have no wonderful shopping mall stories to tell since my childhood. I will say there were times I would stand in the middle of a mall wondering which city I was in because they all look exactly the same. There was something better about getting wet and cold. When we deserted our inner cities for shopping malls, we lost our identities, our uniqueness. Even stores that once stood on their own, lost their specialness in the sterile environment of the mall.

The great thing about my childhood is that we interacted with each other on a more personal level. We had one car per family and we did more things together. So called progress sometimes has a hidden price that isn’t obvious in the beginning. In the 1980s I began traveling the world. In 30 years of travel I found myself always affectionately comparing my experiences to my childhood in Illinois. Then one day the rest of the word caught up with us and there were few special places left.

DOROTHY

One of my mother’s closest friends was the grandmother of two girls, Connie and Kathy, who lived two doors down from my grandmother’s house on Collett Street. Dorothy lived on a farm just over the state line in Indiana. I was privileged to stay on that farm in the summer of 1960, at the age of eleven. Dorothy was very different from my city raised grandmother. She spoke with a heavy Hoosier accent. Dorothy was perhaps one of the wisest women I had ever met. It seemed there was nothing she couldn’t do. Everyday we would cruise the local dumps in her pickup truck. Dorothy would throw the wooden frame of what had once been a couch or chair into the back of the truck, take it home to reupholster, then sell it. The finished product looked like something from a department store showroom.

During my short stays on the farm I learned how to dig post holes, mend fences, slop pigs, and properly shuck corn. Nobody gets a free ride on a farm. But everybody gets to rest on Sunday. On Sundays we would drive to the designated after church farm where all sorts of farm vehicles covered the lawn and a food spread of fried chicken, potato salad, baked beans and pop were laid out in the kitchen. As usual, the guys were in one room and the women were in another room. And we children took our plates of food outside where we could run free to play as soon as we had devoured our lunches.

Driving down an Indiana country road, everybody waved at passing cars. Mostly because everybody knew everybody else. But strangers also got the wave. Many days, after doing our chores, we would walk down the dry dusty road until we reached a stream that ran parallel to the road. Shoes and socks in hand, we would wade through the icy water until the stream abruptly turned away from the road. Then we walked back to the farm on a dry dusty deserted road where sometimes no car or truck had passed for hours. No wonder people waved at passing vehicles. They were happy to see other human beings.

Just behind the farm was a dense forest. Connie took me hiking through the forest as if we were playing in the backyard of their house in Danville. Oh the things that went through my mind when we reached a point where nothing but trees could be seen in every direction. I was a city boy used to street signs and paved roads. But somehow Connie always knew where we were and how to get back to the farm. After a week of walking I learned the signposts in the forest. I even walked solo one day, proudly finding my way back to the farm alone.

Back in the city, Dorothy showed me how she truly was different from my own grandmother. On Saturday nights at the fairgrounds speedway, Dorothy drove a stock car in the races. I couldn’t believe I was sitting in the stands beside two girls who were cheering for their grandmother. To borrow a phrase from that Leave It To Beaver era: “that was really neat!”

From this vantage point 60 years later, I’d have to give credit to Dorothy for being one of the positive influences in my developing years. In her own way she was a rebel, an advocate for women’s equality. She remained my mother’s friend until she died. I will always remember her as a woman of integrity, wise from experience and generous beyond belief.

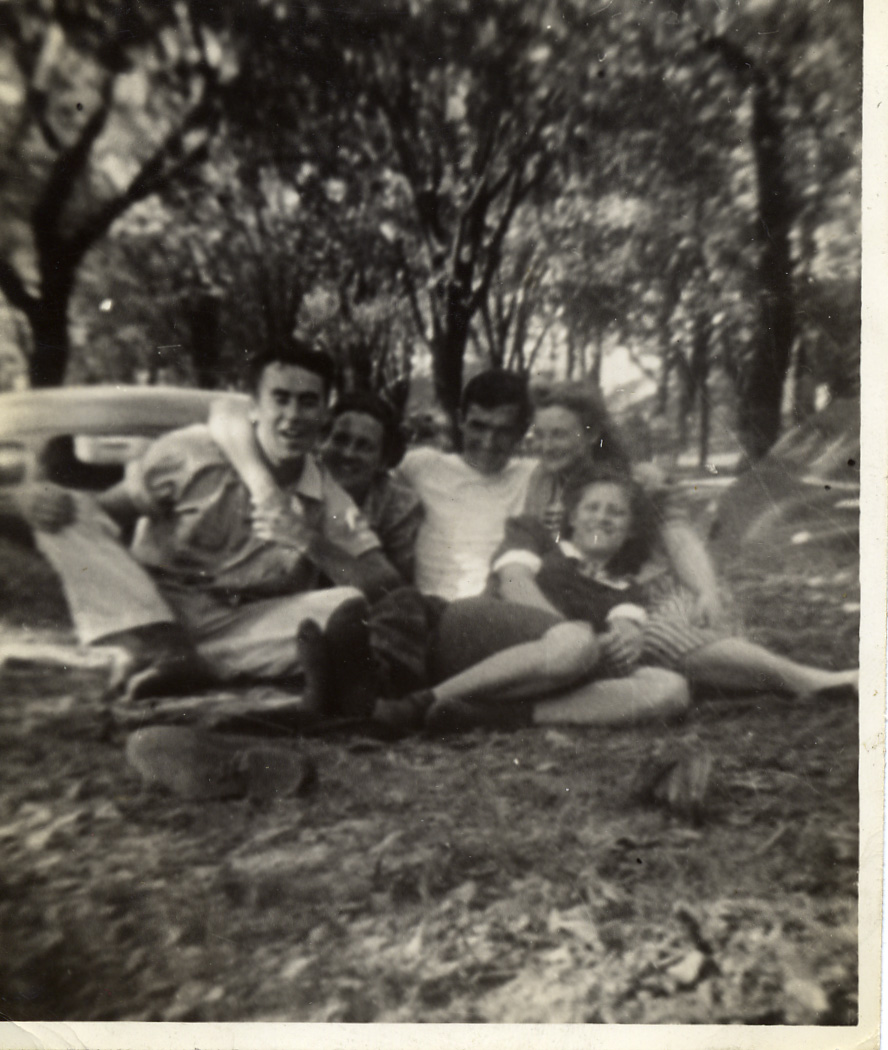

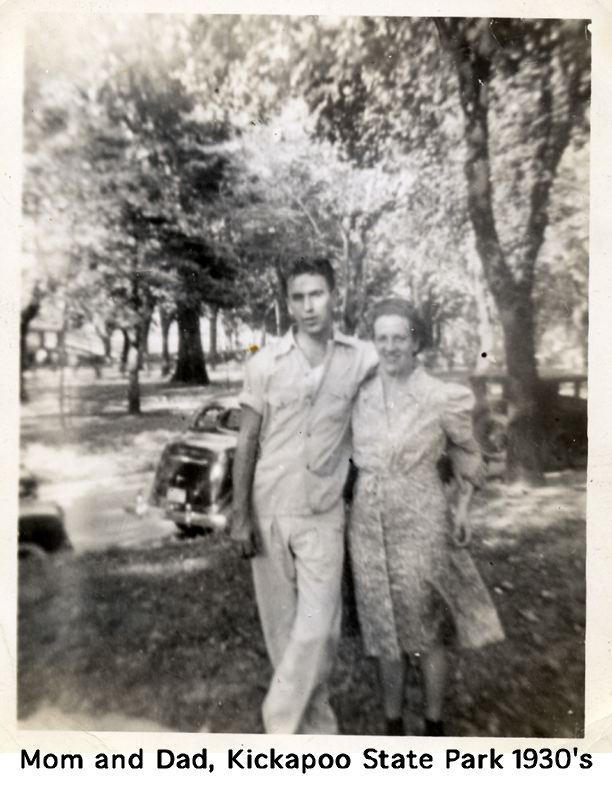

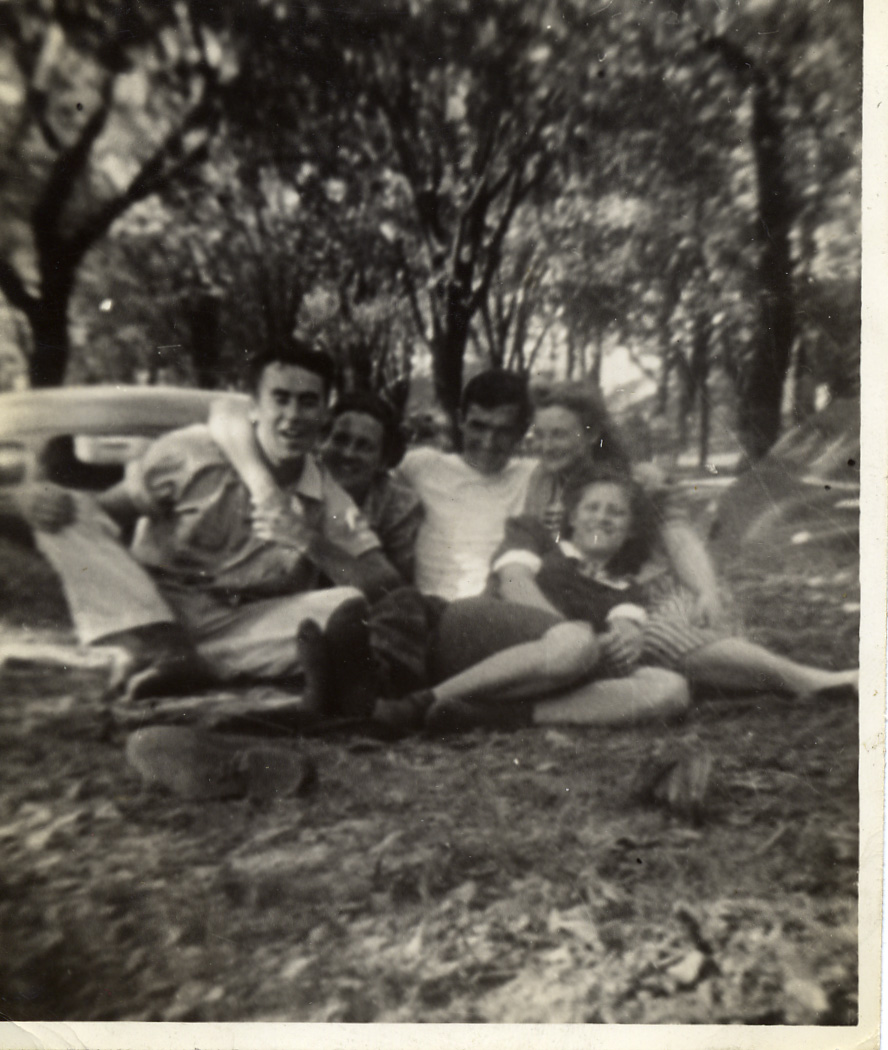

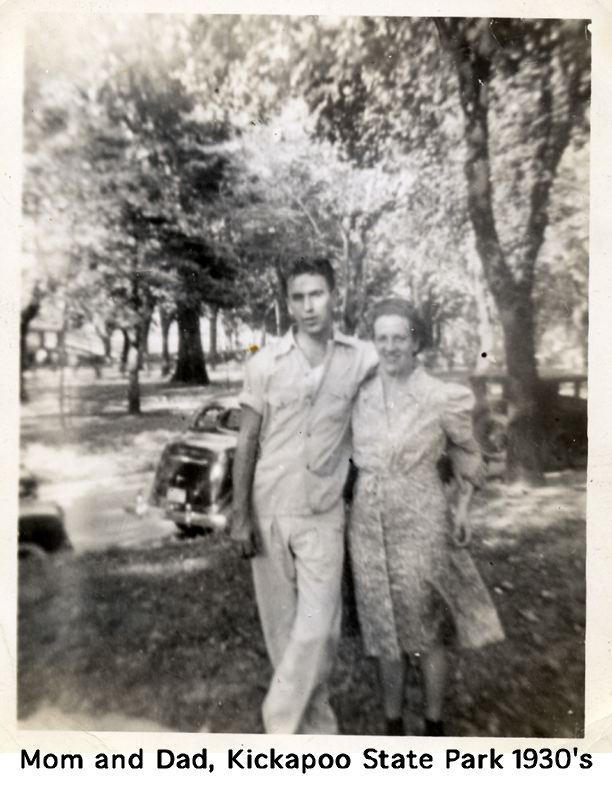

BOB’S MARKET

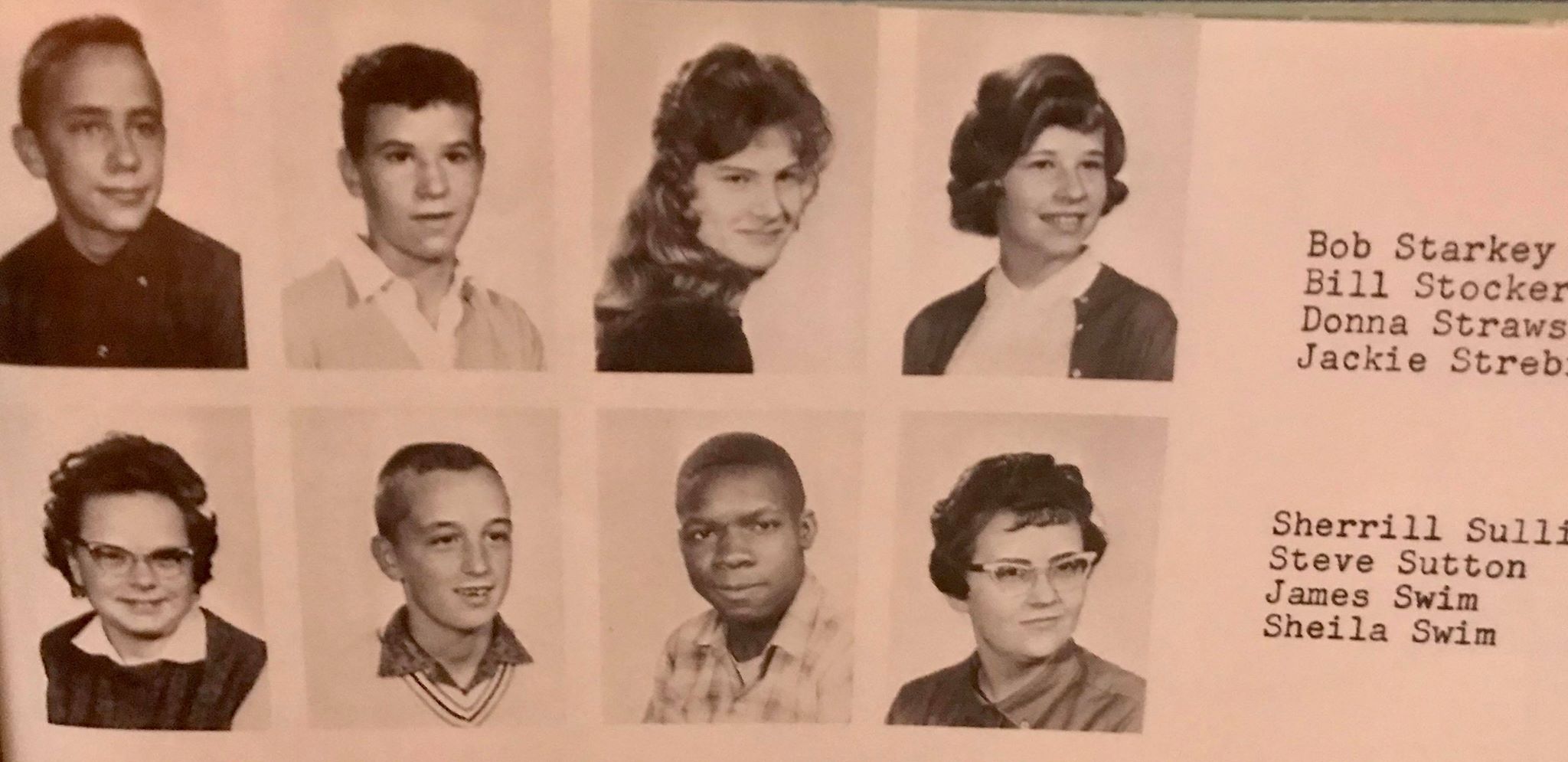

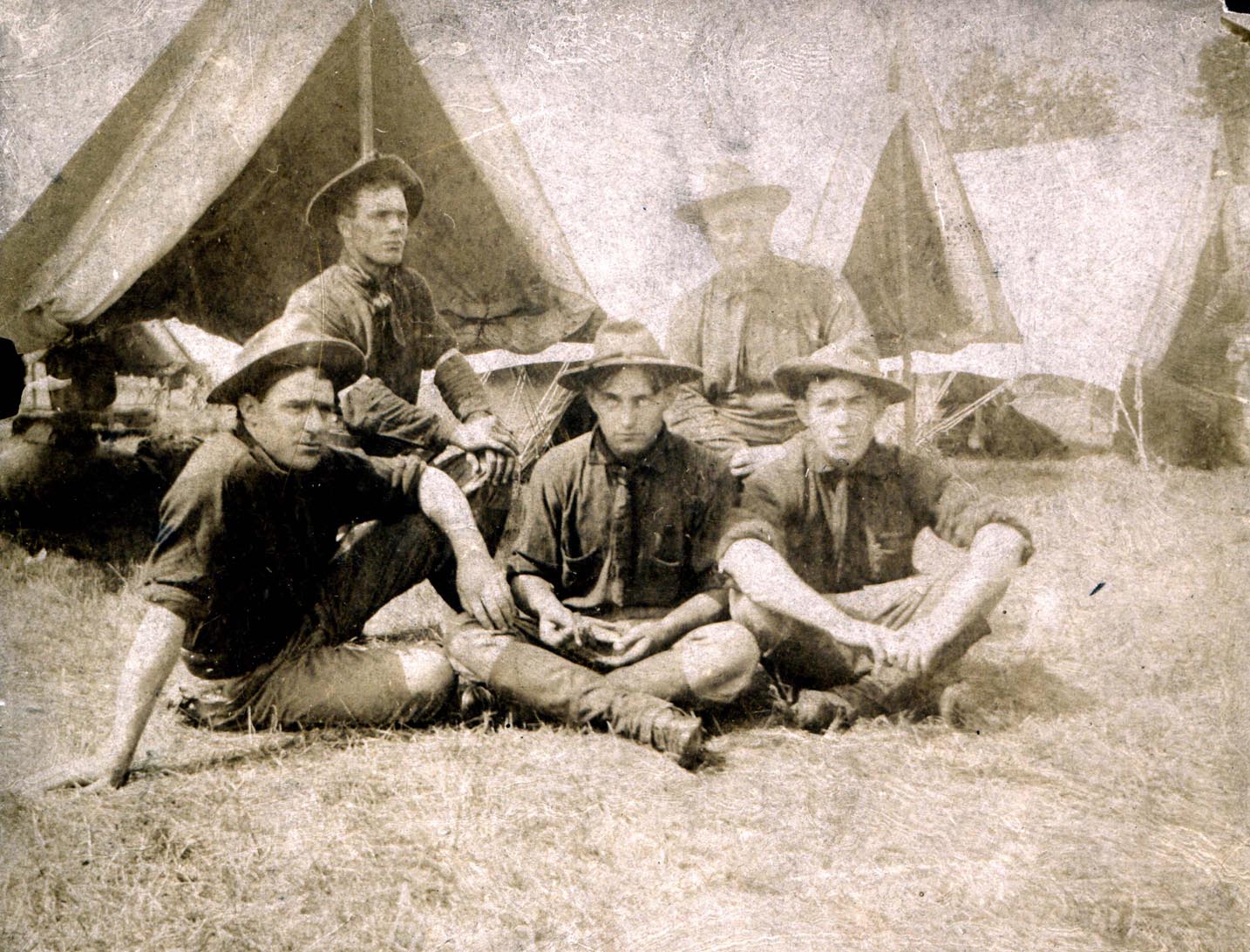

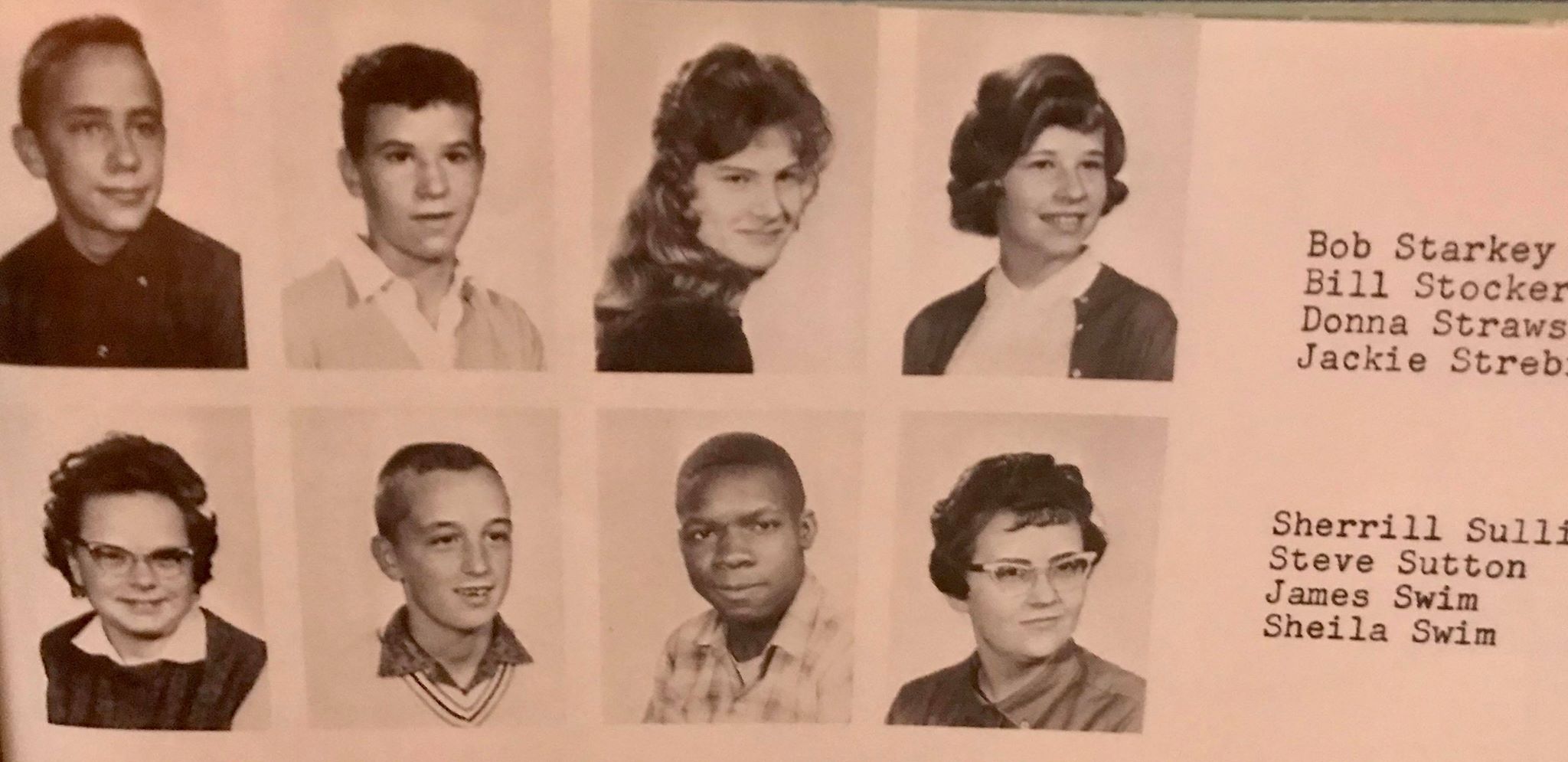

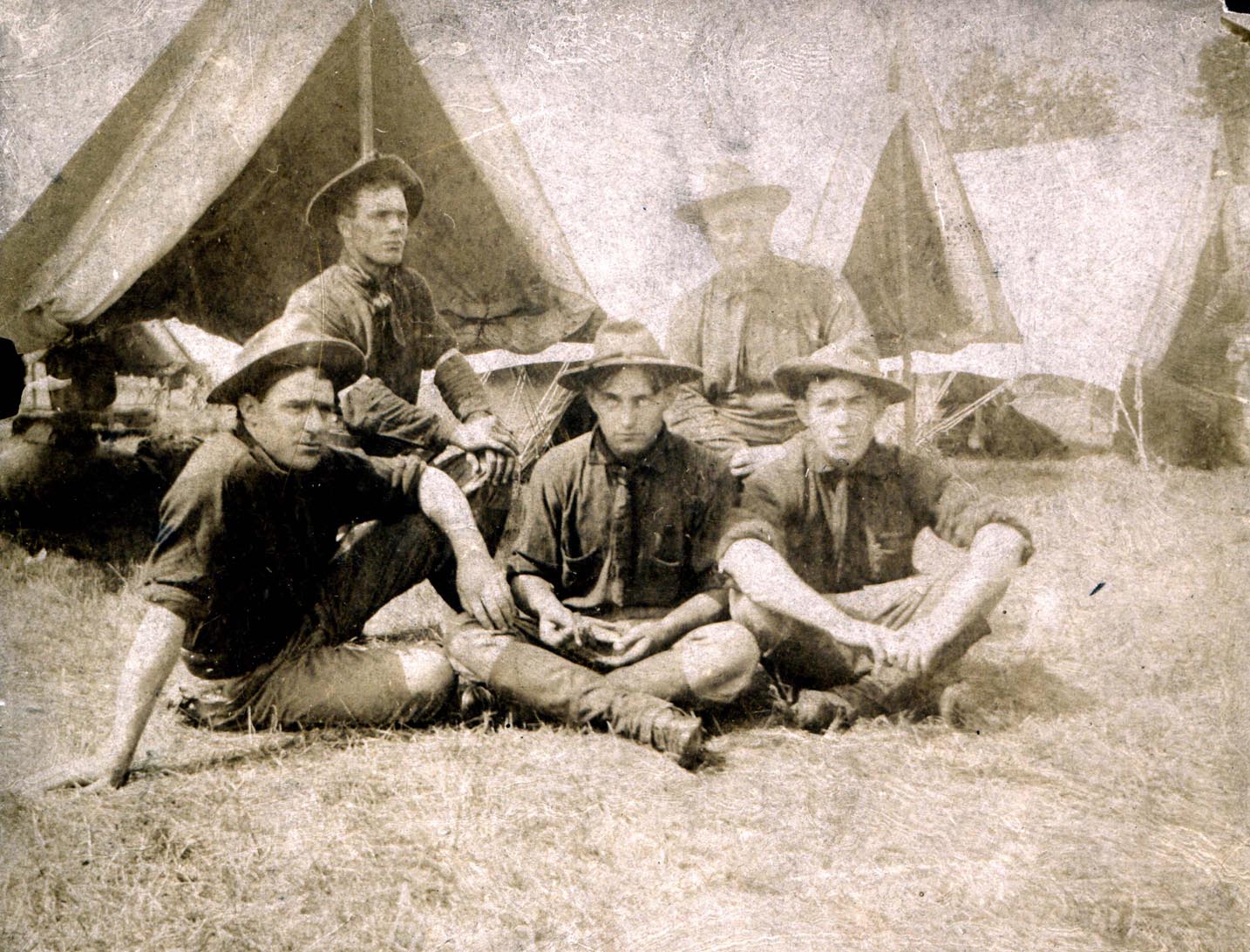

Before they were married, my parents had already formed a friendship that would last for the rest of their lives. Robert Starkey, Mary Dreher, Gertrude Hale and Herbert Wiese were inseparable friends in the 1930s. They picnicked together in Kickapoo Park, went on double dates and celebrated each other’s marriages. During the war, Gertrude (Dottie) and my mom, Mary, looked after each other until the guys returned at the end of the war. Fast forward to the 1950s after I had entered the scene. I believe my mom and Dottie were a lot like Lucy and Ethel.

The Wieses lived on a small farm on Voorhees Street near Bowman Avenue. In the 1950s it was at the edge of the city. Their side of Voorhees Street had yet to be connected to the city sewage lines. I have very distinct memories of the trials of using an outhouse, especially on the coldest nights of the winter. I believe a child’s brain saves special memories in a file that is meant to be opened in later life. My special file is filled with memories of our times with the Wieses.

Let me begin by reminiscing about the farm on Voorhees Street. It eventually became a Wendy’s restaurant. For some reason the first thing I remember is standing on the flatbed of a truck in the driveway, picking apricots from a tree at the edge of the driveway. That memory segues into an autumn wiener roast where a roaring bonfire, in that same driveway, keeps us warm while lighting up the early autumn darkness. Then my memories are drawn to the end of the driveway, where the countryside really begins. I see myself throwing feed to the chickens as they scramble at my feet, pecking at the ground. A few steps further I find myself looking over a low gate while slop from the local dairy on Vermilion Street is being poured into the feeding trough for the pigs. I remember the smell of bacon and stacks pf pancakes slathered with butter and syrup on a Sunday morning, after an overnight stay.

My parents and Mick and Dottie played cards on Saturday nights. They alternated hosting every other weekend. The thing I looked forward to were the differences in the Saturday nights at the Wieses. They were an RC Cola family and we were a Pepsi family. They offered Cheese Puffs while we had potato chips. But everybody had the same sour cream onion dip! And we could always count on the standards, mixed nuts and pretzels as we played board games, watched TV or played our own versions of cards.

We traveled together as a family. I remember the long and dangerous drive from Danville to Chicago on route 1, to visit the Brookfield Zoo. Every time my father would push the pedal to the floor, to pass a slower driver, we would all hold our collective breath until we were safe back in the proper lane. Just outside of Chicago my father became concerned about a constant hissing sound. He motioned for Mick to pull over so he could check the engine. That’s when they discovered we were driving into a plague of locust. At the zoo, it was fun watching women screaming as locust landed in their hair. I remember women with huge wide push brooms sweeping up piles of locust from the walkways. Our parents bought us pointed Chinese hats to protect our heads. You know, all these years later, I can’t remember seeing any animals at the zoo. The locust stole the show.

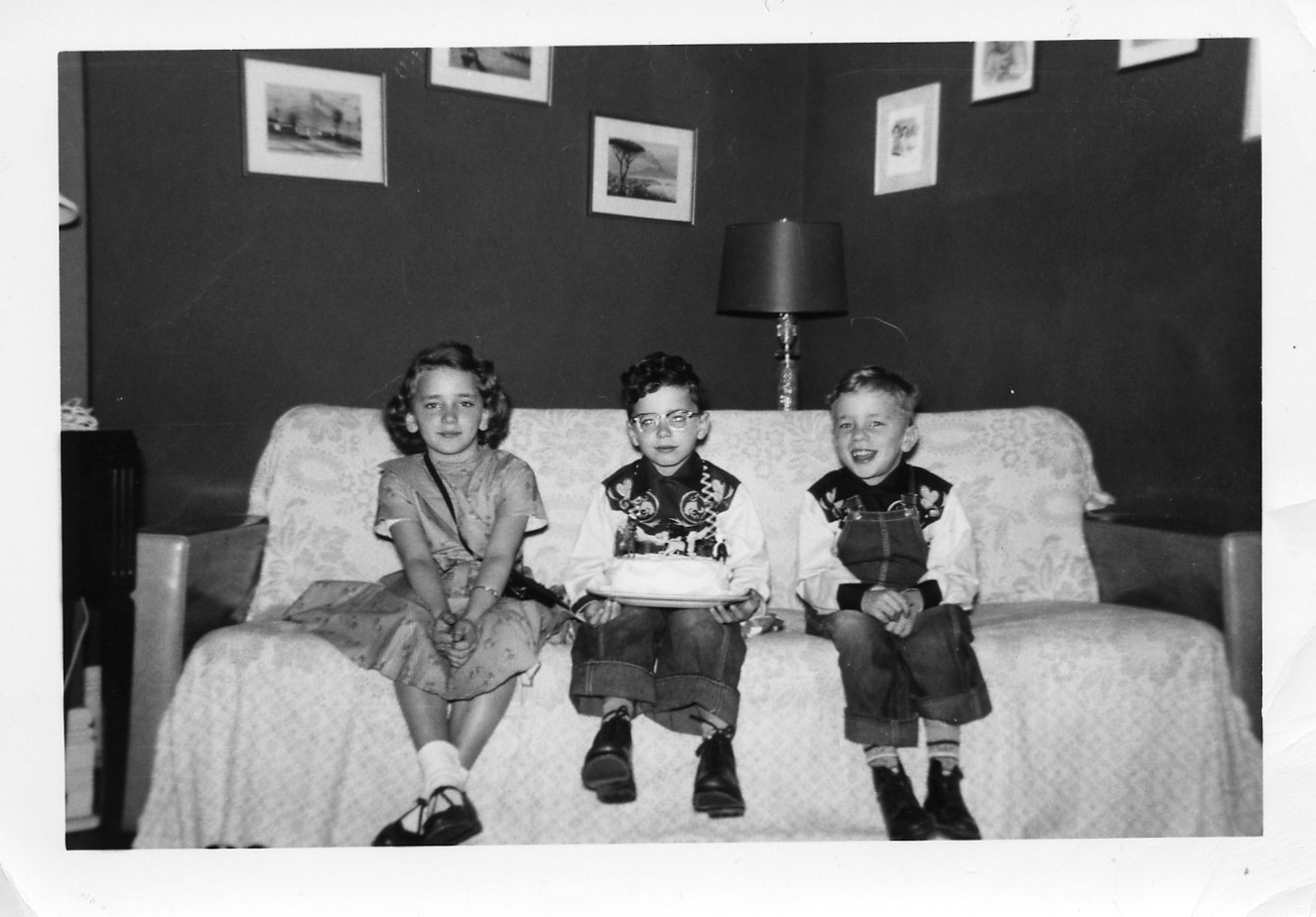

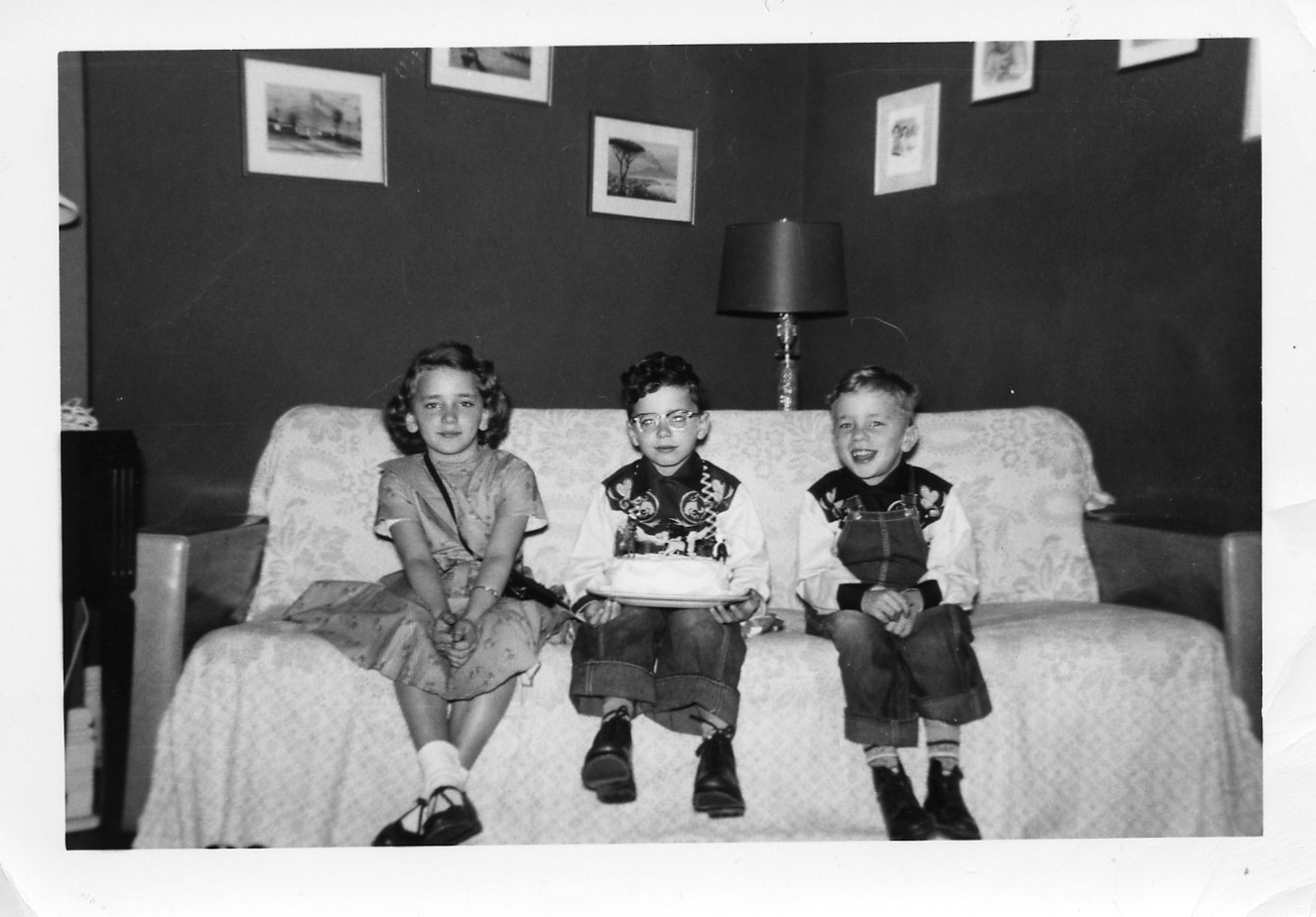

The furthest trip together was to Lake Tomahawk in Wisconsin, to a fishing camp where we stayed in cabins. One morning we got up long before sunrise and the boys joined our fathers in a day long fishing trip. I was mesmerized when the motors were turned off and paddles were used to push the boats through dense grasses to reveal a remote portion of the lake unaccessible by any other means. As we parted the last blades of grass, the sun rose over the east shore of the lake turning the water a bright red/orange. In the distance I could see a buck with a huge set of antlers gracefully dancing away into the forest and out of sight. When we returned to the camp later in the day I grabbed my camera to record the event. Bob Wiese and my brother Steve proudly held the day’s catch as my sister Chris looked on. But the thing I took away from that fishing trip was the image of the sunrise on the remote lake. Throughout my life I would have dreams where I would paddle through high grass to a peaceful lake, sometimes on the other side of the world, where I felt safe and secure.

Whenever I returned to Danville, my trips to Bob’s Market were always about reminiscing about old times. But the thing I remember most is when Bob and I were pulling a wagon through the streets of Danville selling vegetables door to door. You’ve come a long way baby!

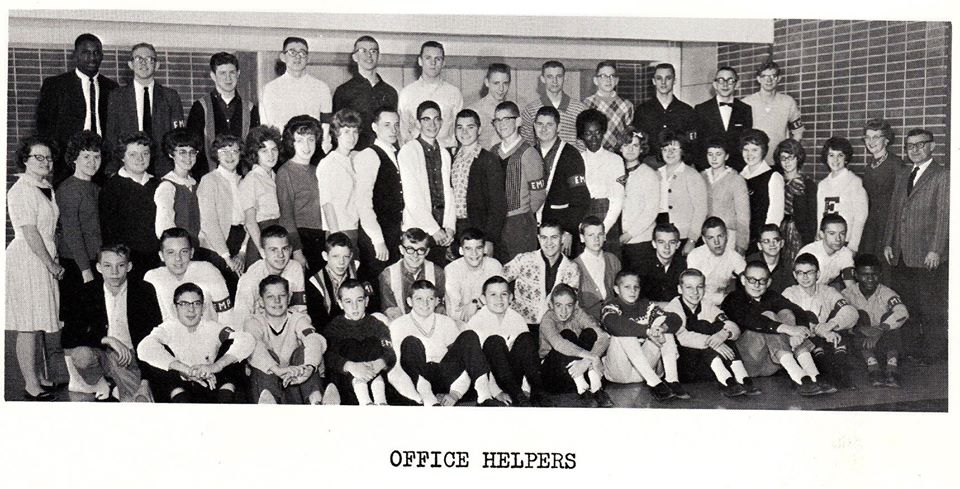

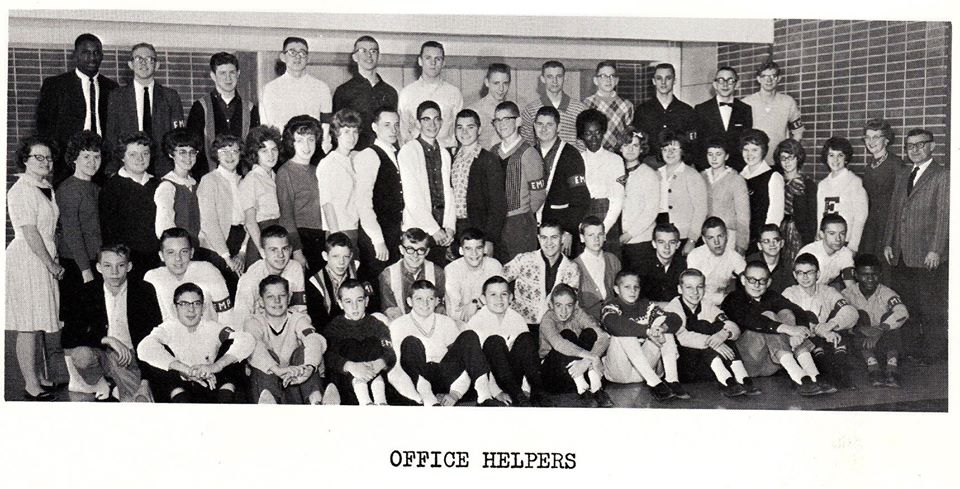

EAST PARK JUNIOR HIGH

The first thing I remember about East Park Junior High School happened during my first year. I had an English teacher who assigned us a project to write a poem. All these years later I don’t even know her name, but I owe her my gratitude. After the papers were graded and returned to us, she asked me to stay behind after class. She told me my poem was the best piece of writing she had seen from a 12 year old. She wanted me to promise I’d keep writing. She said all I needed to do was write as much as possible. I’m not sure if I believed her or not in that moment, but she planted a seed in my mind. That was a pivotal moment in my life, the example of how a good teacher inspires her students. She inspired me by making me feel special. I started writing my experiences and kept them to this day.

Here is the poem, found among my notes many years later:

God made our eyes so we could see

God made the honey for the bee

But he gave me a special gift

When he made you especially for me

Now in my eye there lay a tear

Just like a drop of dew

For he made one mistake my dear

He forgot to make me for you

My first year at East Park was also East Park’s first year of existence. One image that is seared into my memories is the experience of walking down hallways littered with buckets catching rainwater leaking from a badly designed roof. The roofs were flat and the rainwater gathered on the rooftops like small ponds. I saw one classroom completely closed as water ran down the walls in sheets.

I remember music class with Mr. Perkins. Every Thursday Mr. Perkins would ask who is wearing red socks? You know what they say about men who wear red socks on Thursday! Is it ironic that Mr. Perkins often chose to wear red socks on Thursday? Then there was the very carefully constructed poem about chewing gum. “A gum chewing girl and a cud chewing cow, are somewhat alike somehow. Oh yes, I see the difference now. It’s the thoughtful look on the face of the cow!”

On November 22, 1963, I was lying on the floor of the gym doing sit-ups with the rest of my gym classmates. Our gym teacher came out to the middle of the floor and solemnly announced that President Kennedy had been shot. In the locker room he gave us a crash course on the line of succession. Then came the final blow. The president was dead! We were all sent home to our parents where we were glued to the television, watching history unfold in black and white.

The next spring, 1964, the school principal Mr. Yeazel took a group of boys, hall monitors, on a field trip to Chicago, to the Museum of Science and Industry. Once I got inside the museum I don’t remember seeing any of the other boys until we got back on the bus. That was my first exposure to museums. I often wonder if these special teachers and principals understand that going beyond the perimeters of their lesson plans can have such lasting positive effects on their students.

THROUGH A CHILD’S EYES

When I close my eyes to imagine I’m young again, it really is like Alice falling through the looking glass. Through my child’s eyes the distance from my home to the corner seemed so much further than it really was. For years I thought my mother had a really forceful voice when she stood on the front porch calling us home at bedtime. Until I stood on that porch 50 years after moving away, it never occurred to me that my mother had been within shouting distance. From my child’s perspective the year was divided into two equal parts, summer vacation and the school year. From Memorial Day to Labor Day, my child’s mind invested every ounce of energy in denial of the impending return to studies in September. From September until May, I lived for the holidays and snow days, never taking my focus off the return of summer.

We children were so easy to please in the 1950s. I remember taking large pieces of cardboard boxes to the hills where we had gone sledding in the dead of winter. We slid down the hill on our summer fashioned sleds with the same enthusiasm and screams of joy we had on the snow. But we had no frozen toes or fingers. Just mosquito bites and sunburns. We easily accepted the idea that an inflatable circular plastic bowl that held no more than 6 inches of water was really a swimming pool. I don’t remember anyone in my circle of friends who knew how to play dominoes, so we carefully placed them on their sides spaced just enough apart, curving like a snake, then delighted in watching them fall “like third world countries succumbing to communism.”

There’s a lot to be said about the concept of an expanding mind. It would be great if we could all keep the innocence of a child while also learning about all the world has to offer. There’s also a lot of truth in the concept of a second childhood. Perhaps we should all think about the idea we have all repeated from time to time throughout our lives. “If only I knew then, what I know now.” What a great idea as we all approach our second childhoods. Let’s combine the innocence of childhood and the wisdom of age as we go forward.

DICK VAN DYKE

One of my first jobs as a budding photo journalist took place in March 1963, in my hometown, Danville, Illinois. I was 14 years old. Like every other inhabitant of Danville, I was glued to the television set every Tuesday evening for the next episode of The Dick Van Dyke Show. Occasionally the newspaper would warn us that Dick was going to mention Danville in his next show. I would ride my bicycle to my sister Pat’s house on Grove Street near Cleveland Avenue. to watch the show. When Dick actually said the word Danville, we would scream, “he said it, he actually said it!” We all got some personal satisfaction that for a fleeting moment people in Amsterdam were asking themselves, “where is this place called Danville?”

In March, 1963, the city of Danville had declared one day, Dick Van Dyke Day, complete with parade. I ran beside the yellow antique convertible snapping away, even managing to get an autograph. All my excellent pictures along with the newspaper articles and autograph were proudly displayed in an album that unfortunately got lost when I moved to Berlin in 1991.

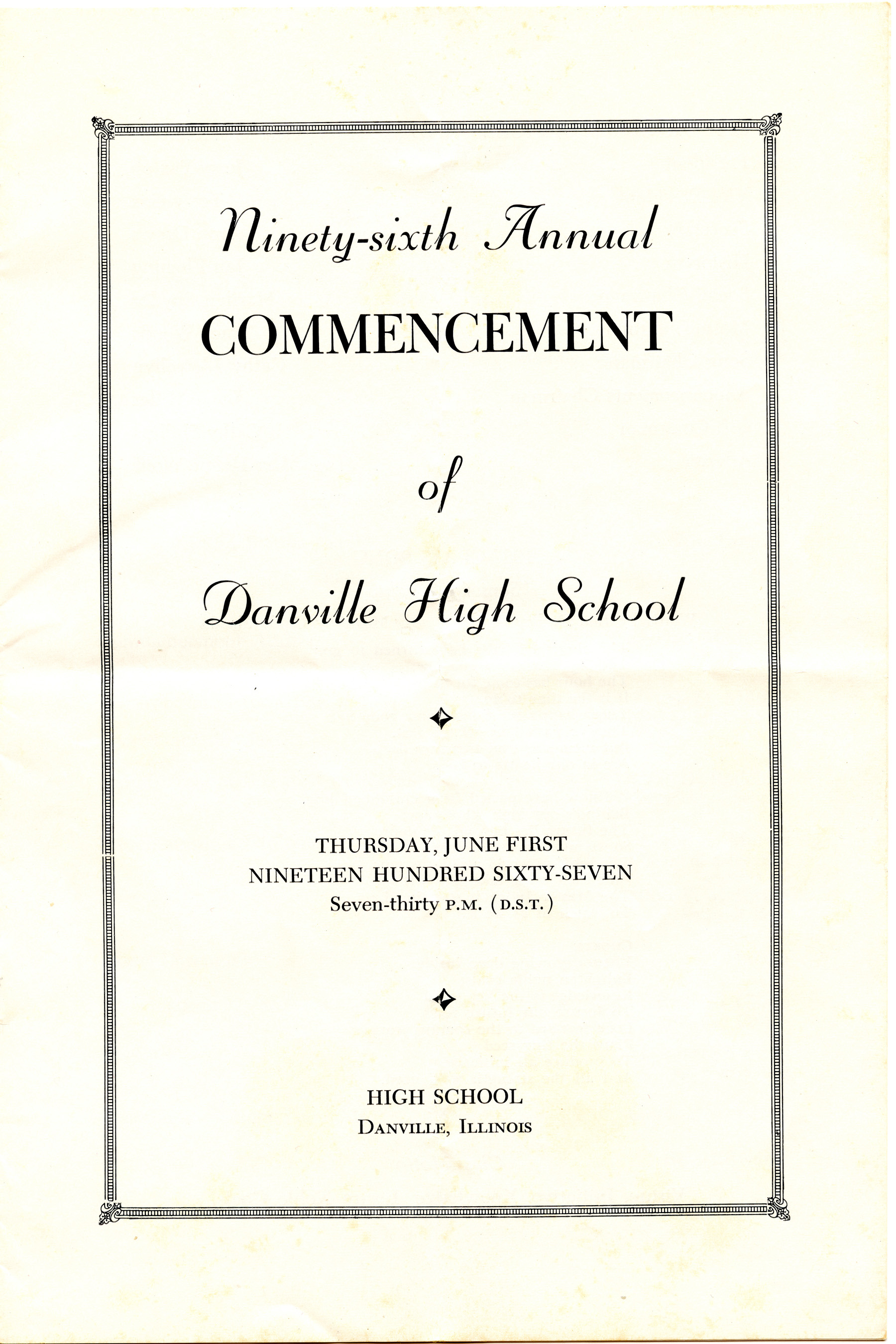

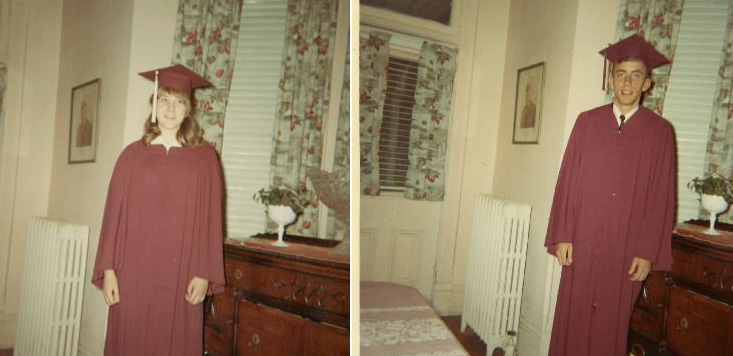

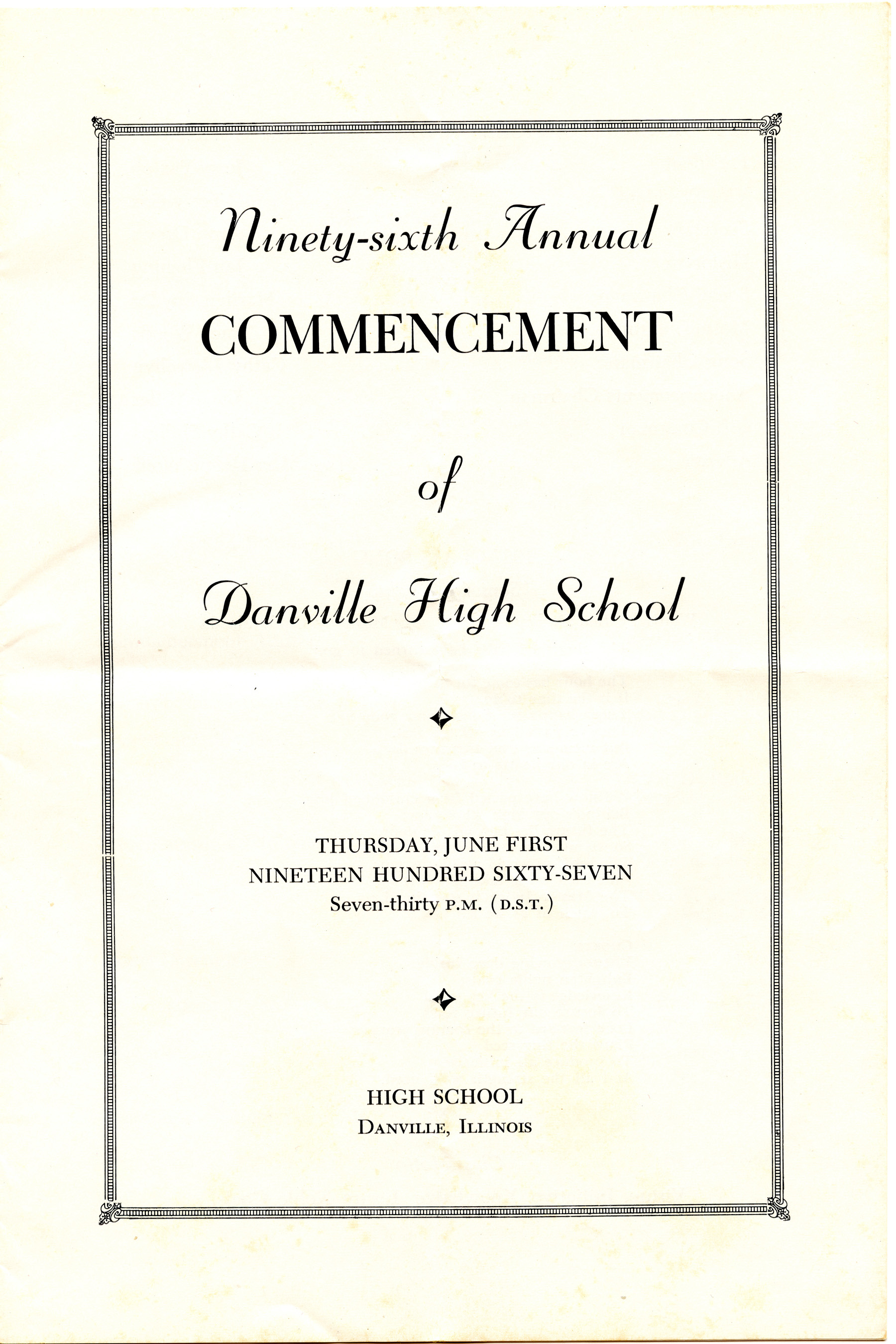

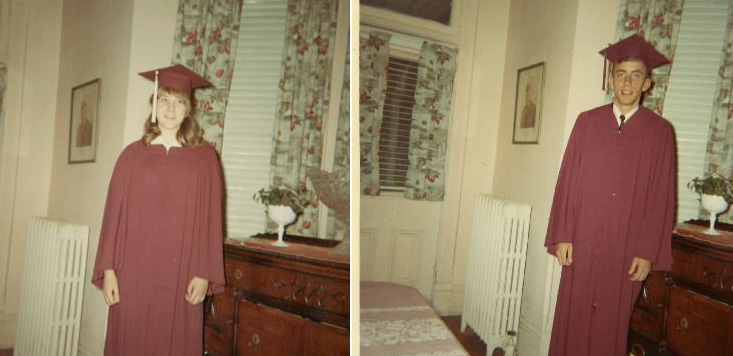

In 1964, I sat in a packed Fisher theater along with my fellow Danvillians waiting for the premier of the movie, “Mary Poppins.” I had read reviews in Chicago newspapers as well as the New York Times. I was very well read for a 15 year old boy in Central Illinois, thanks to a decently stocked newspaper stand on the square in the Plaza Hotel. When Bert (Dick Van Dyke) began dancing with cartoon characters, the audience became very animated. “They didn’t see the reviews,” I thought to myself. Otherwise they would have known about the cartoon characters. It was the talk of Hollywood. In 1967, for my graduation, my husband Larry and I drove to California. On top of our list of sights was a drive by Dick Van Dyke’s house.

Through the years my mother would get calls from relatives and friends telling her “Dick is in town!” My mother and Dick Van Dyke were both born on December 13. Somehow, someone arranged for my mother to send Dick a birthday card and the next year my mother received a birthday card from Dick in return. To this day I have a signed picture of Dick as Bert the chimney sweep. As I have gotten older, the Bert in the photo has gotten younger.

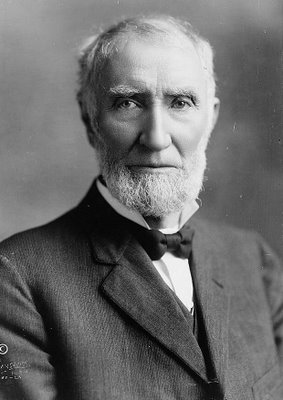

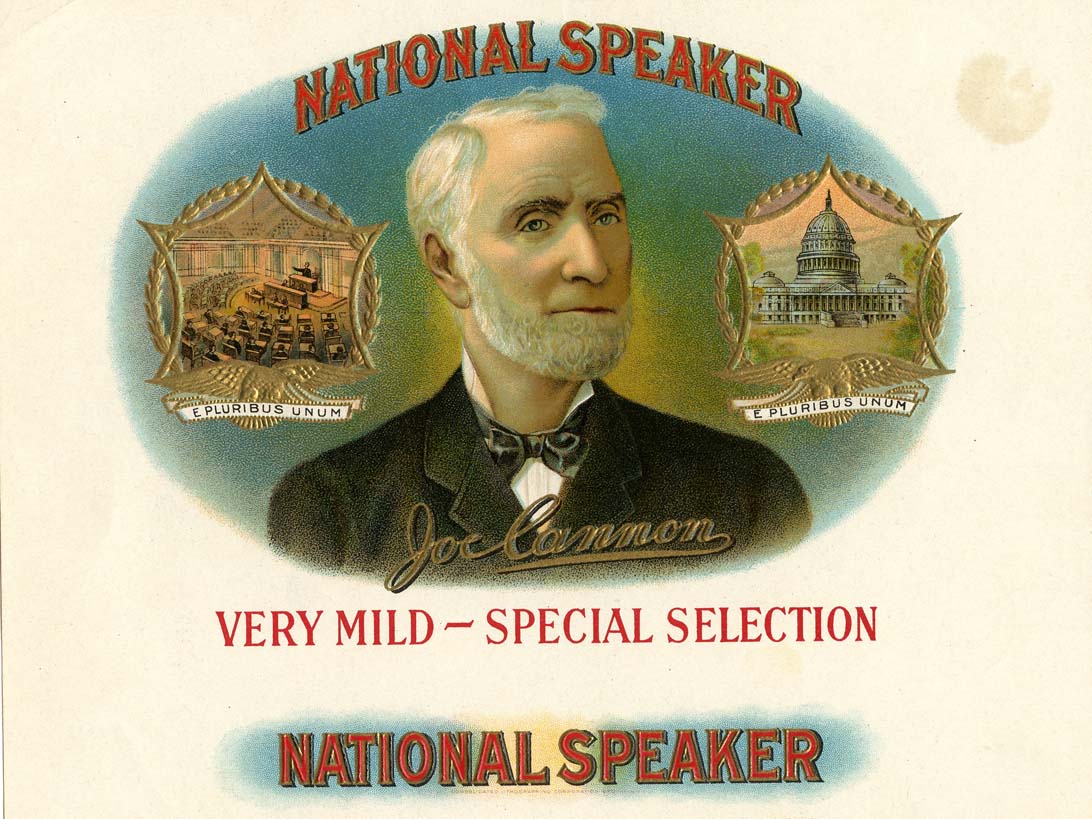

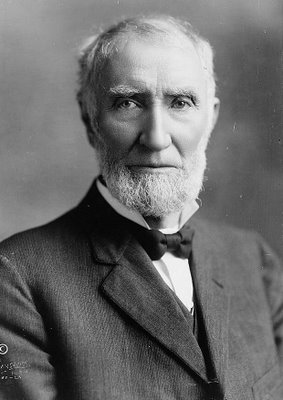

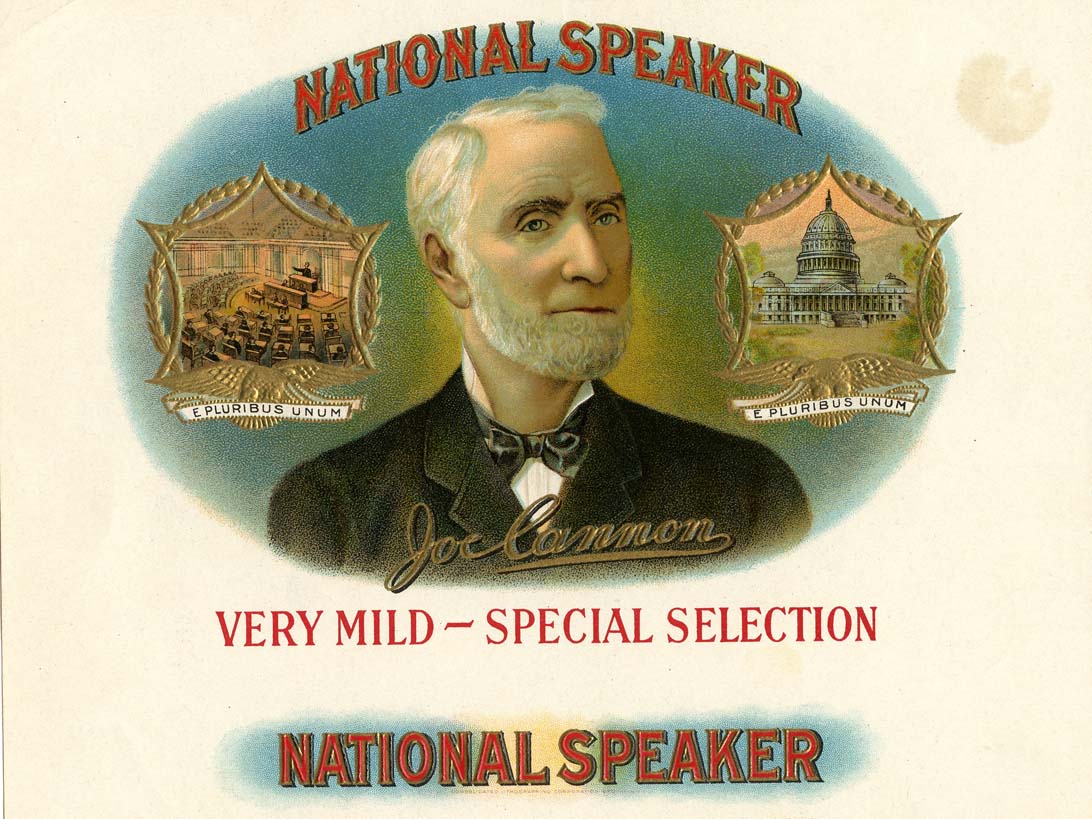

Needless to say, most people from Danville, even today, can rattle off the names of Danville’s celebrities, Dick Van Dyke and Jerry Van Dyke, Gene Hackman, Bobby Short, Donald O’Connor as well as Helen Morgan, Uncle Joe Cannon and Joe Tanner.

GRIGGS STREET

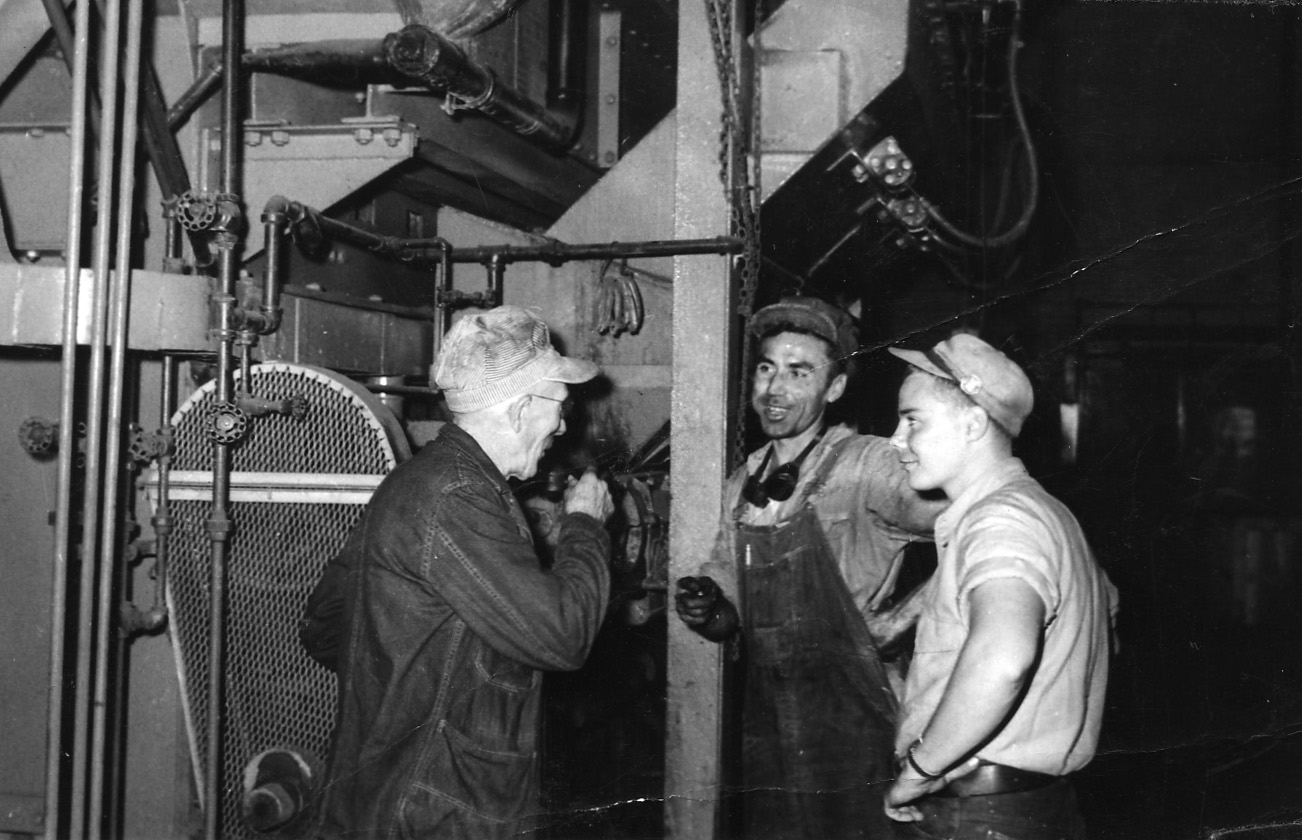

My grandmother’s house was on the west side of Collett Street, bordering a small industrial area to the west. Behind the first three houses was a trucking company where semi-trucks would back up their trailers to be unloaded. Behind our house, the Weller’s and the Testa’s was a small foundry, McEnglevan, that manufactured furnaces and accessories for factories. Across from McEnglevan, on Griggs Street was a dog food factory.

The sidewalk in front of McEnglevan’s was on a big slope that was perfect for maximizing the speed of our homemade go kart that consisted of a few two by fours and and old wheels from a wagon. It was also the perfect playground when we discovers metal clip-on roller skates. In the winter we used sleds in the middle if the street. There was never any traffic to speak of, especially after a snowstorm. There was nothing more exciting than sledding down Griggs Street after an ice storm.

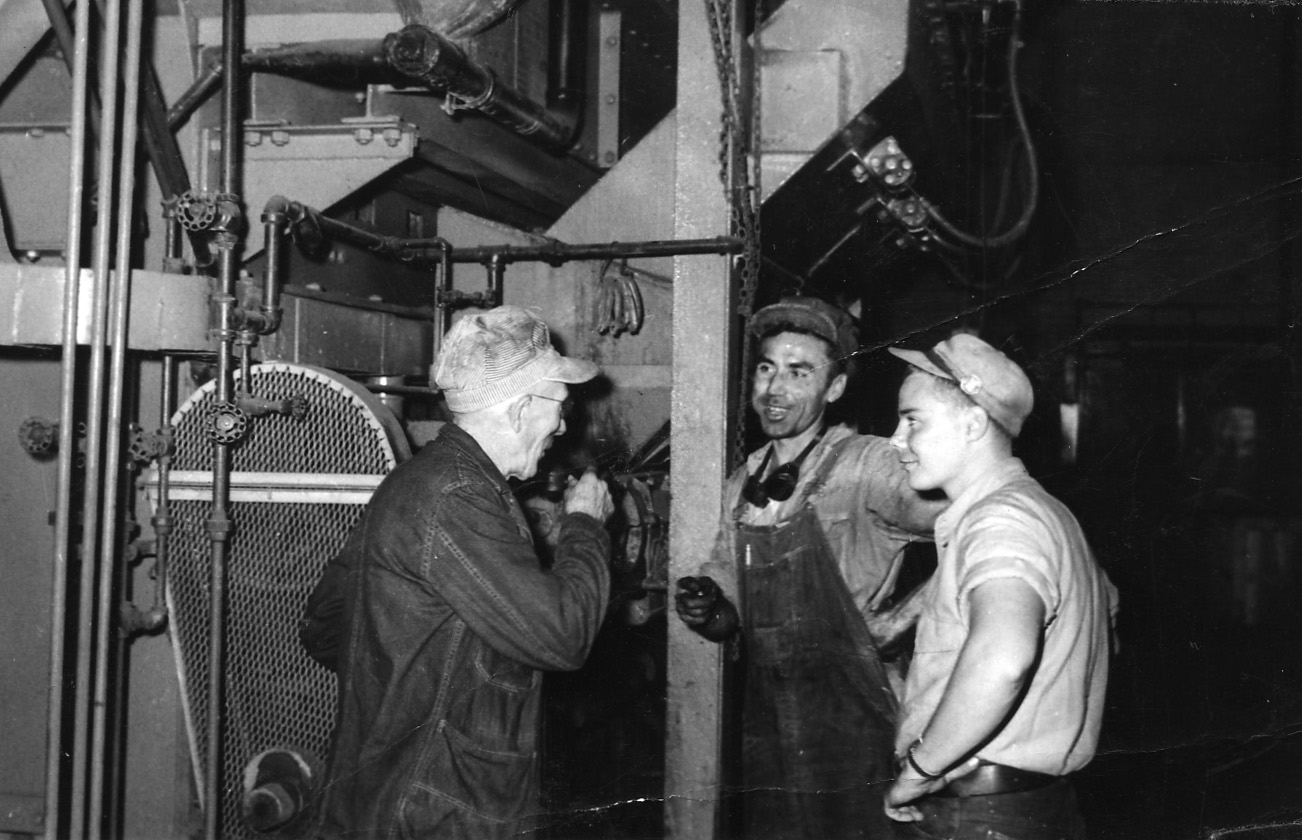

Just beyond the alley on Griggs Street, behind the Testa’s house, was the main entry to the foundry with its hot molten steel. All the kids knew the names of the workers and they knew our names. In a way we were constant companions. Directly behind our house was an empty field that gave us a clear view to Anderson Street. To the right, in a small cove cradled on two sides by the foundry and its offices, there were several old furnaces that sat rusting in the elements. On Sundays we had free reign over the the abandoned furnaces. One became a WW2 submarine. Another was a bomb shelter to protect us from the impending armageddon. One Sunday, one of the workers arrived in a pickup, pulled up to the back entrance and carried out the safe from the offices. Of course he was immediately arrested and it was the talk of the foundry on Monday morning. We were not witnesses, but we wondered what would have happened if we had witnessed the great McEnglevan heist!

One summer McEnglevan added a new addition to the factory with a metal roof that required thousands of rivets. The alleyway was littered with unused rivets that had fallen from the scaffolding during construction. The guys in the factory made a deal with us. They gave us a penny apiece for every rivet we returned to them. I don’t really think they needed them back. They were just being nice. And we appreciated their kindness as we chose penny candies at Timm’s Grocery across the street. When we had collected 100 rivets, we were handed a one dollar bill that made us feel really important. Actually having paper money was a big deal in a child’s financial world that usually consisted of coins only. Most of the time only pennies.

I feel lucky to have grown up in what would today be considered an unsafe environment. We were street wise because we lived in that environment. We stood at the side of the railroad tracks as the north and south bound Illinois Central passenger trains sped through at the intersection of Griggs Street. We waved patiently until someone, anyone, waved back from the train. Then we walked away with gratified smiles on our faces, knowing that we had for one second been acknowledged by someone free enough to travel on trains. For one brief moment we had injected ourselves into a life we wanted to be a part of someday.

At such a young age we were quite the entrepreneurs. Across the tracks was the “junk yard.” My mother did the owner’s laundry. When we would run out of candy money, we would roll our trusty little red wagon around the neighborhood picking up every piece of metal we could find. We would proudly walk upon the scales with the wagon to have our entry weight taken, then pull the wagon into the yard to dump it. We returned to the scale for the exit weight and Jerry would give us money for the metal. Then it was off to Smitty’s for more penny candy.

One day a stray cat wandered into our world. None of our parents would let us have a cat. So we decided to build a “cat house’” for our new friend. We went to the nearby lumber yard to ask if we could have scrap wood to build a cat house. We did not understand why everyone was laughing. It didn’t matter though, because they told us we could have as much scrap lumber as we could carry, on one condition. That we would let them know when the cat house was finished.

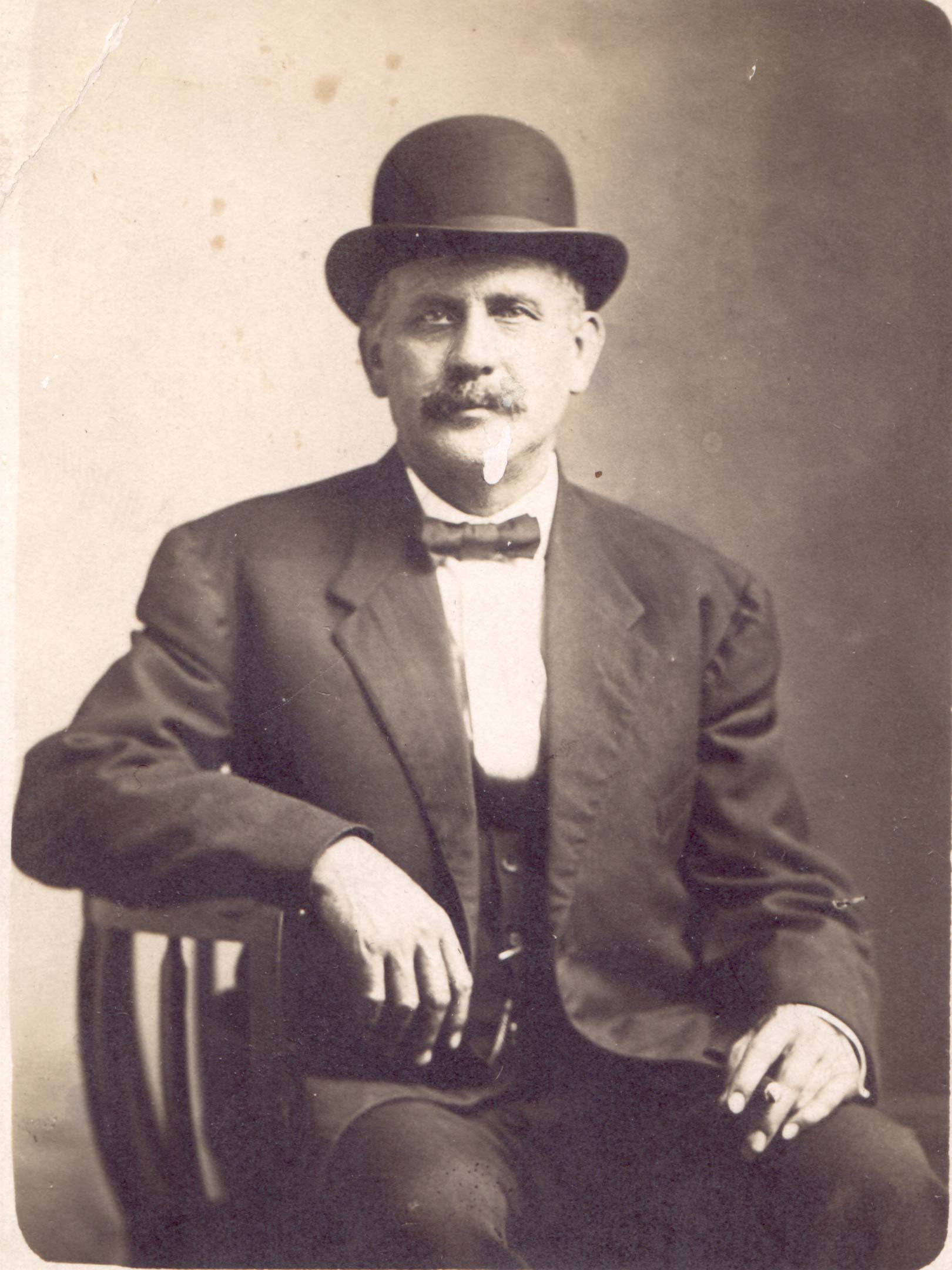

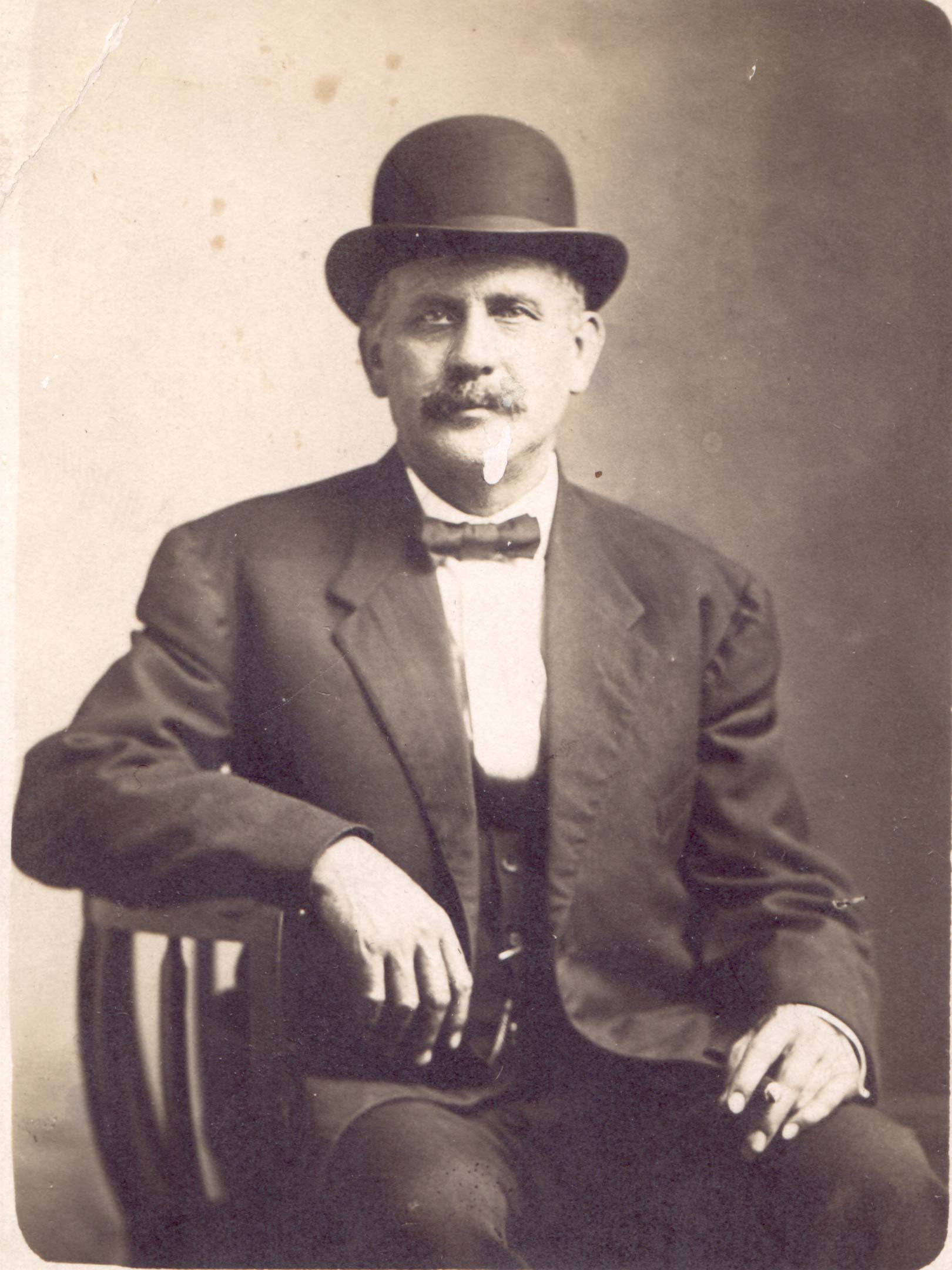

GERMANTOWN

My great grandfather was born on July 6, 1856, in Rustow, Germany. In 1879, at the age of 23, Ludwig Wahlfeldt set sail for New York. He went directly to Danville, Illinois from New York to join other skilled Germans attracted by jobs at the C&EI Railroad shops. Ludwig worked the next twenty years as a car repairman at the Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad shops. He would remain in Danville for the rest of his life. During Mayor John Smith’s administration (Louis) Wahlfeldt was appointed chief of police in Germantown, and remained in that position five years, until Germantown was annexed to the city of Danville. Germantown got its name because of all the skilled German workers who settled in the neighborhood to be close to their jobs at the C&EI railroad shops.

On April 15, 1916, my great grandfather Ludwig Wahlfeldt died from stomach cancer, leaving nine children behind. On July 4, 1916, Ludwig’s daughter, Martha Starkey gave birth to my father Robert Starkey. My grandmother was a founding member of the Immanuel Lutheran church at the corner of Fairchild and Griffin Streets. Growing up in my grandmother’s house was my connection to my roots. Grandma taught me my first words in German by teaching me to sing Silent Night, (Stille Nacht). From the time I was a young boy, until I was a young man, I would sit with my grandmother in her room, as she proudly turned the familiar pages of her photo album, passing her stories on to me.

Because I grew up in Germantown, my experience as a child was as much German as it was American. The twentieth century saw a lot of melting in the melting pot. But the American experience is not an annihilation of our heritage. It is an incorporation of the best of what the immigrants brought with them when they came here for a better life. When I am in my German/American mode you may find me eating bratwurst and sauerkraut. But when I’m in my American mode, you may find me eating spaghetti or udon, burritos or dolmathakia, tom kha gai or jook, fry bread or sourdough, corn on the cob or hamburgers. When I think of my concept of America I see all the colors of the rainbow.

LAKE VERMILION

There’s a saying that time seems to go faster as we get older. A quarter of an 8 year old’s life is 2 years. A quarter of an 80 year old’s life is 20 years. Today we have entire PBS documentaries dedicated to explaining the complexities of time perception in the human mind. But one thing is simple. When we were children, three months of summer vacation seemed much longer than it does now. Thank heaven for that!

The other perception that changes with age and experience is distance. When we take our first steps, the distance from Dad’s arms to Mom’s arms seems insurmountable. Under the watchful eyes of an older sister or brother, one day our boundaries extend to the perimeters of our backyard. The third step to freedom is noticeable when Mom trusts us to go to the end of the block, as long as we can respond to the sound of her voice calling us to supper from the front porch. Step four is when we children become aware that Mom only calls us at lunch time or supper time. We quietly sneak beyond the boundaries, always sure to be back inside when Mom calls. Step five is the realization that Mom doesn’t call us anymore. We test our freedom in increments until one day we get the courage to run far beyond the boundaries without looking back. That freedom came for me on a warm spring day in 1961 when patches of leftover snow drifts were still melting into the gutters.

I rode my new bicycle north on Collett Street until it turned right, becoming Fairchild. I crossed over the tracks that led to Chicago on the left and New Orleans on the right. As I passed the passenger depot, I was confident of the day I would walk up to the teller to buy a ticket to Chicago on my own. But on that day my sights were on something more attainable. I was intent on riding my bike to Lake Vermilion. As I turned left on Bowman Avenue, setting my sights on Voorhees Street, I realized I had never been beyond the Germantown drug store alone. I was in new territory and it felt liberating. When I reached Logan Avenue I knew I was getting close. I passed the small white cottage in the 1500 block of Logan Avenue where my father had lived as a child. What a privilege it would be to live so near the lake, I thought to myself. Each of these seemingly small impressions would become parts of who I became as an adult. I would never lose that desire to go just beyond the next perceived boundary.

On the evening of January 16, 1994, just hours before a destructive Los Angeles earthquake, I departed L.A. on a Korean Airlines flight headed west to Southeast Asia. For the following 12 months I kept traveling west until I was back in San Francisco one year later. Thirty-three years after my great escape to Lake Vermilion, I broke the final barrier.

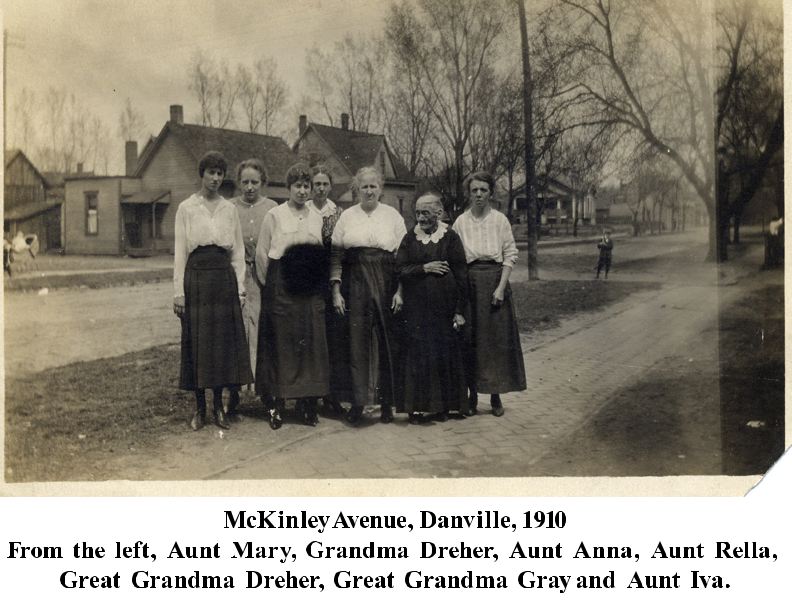

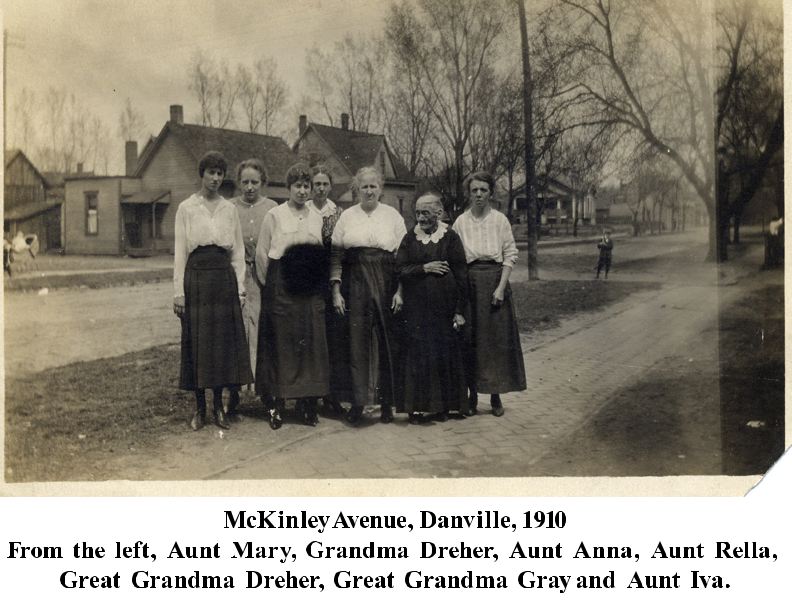

McKINLEY AVENUE

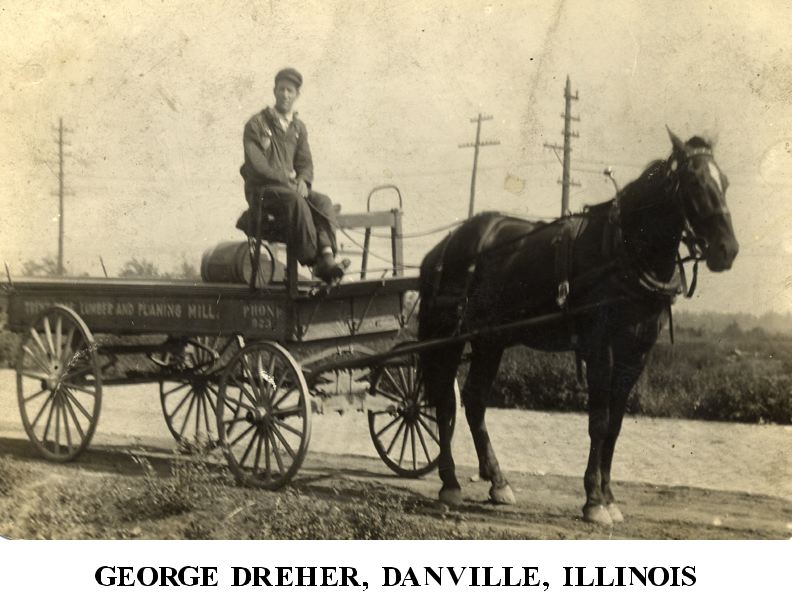

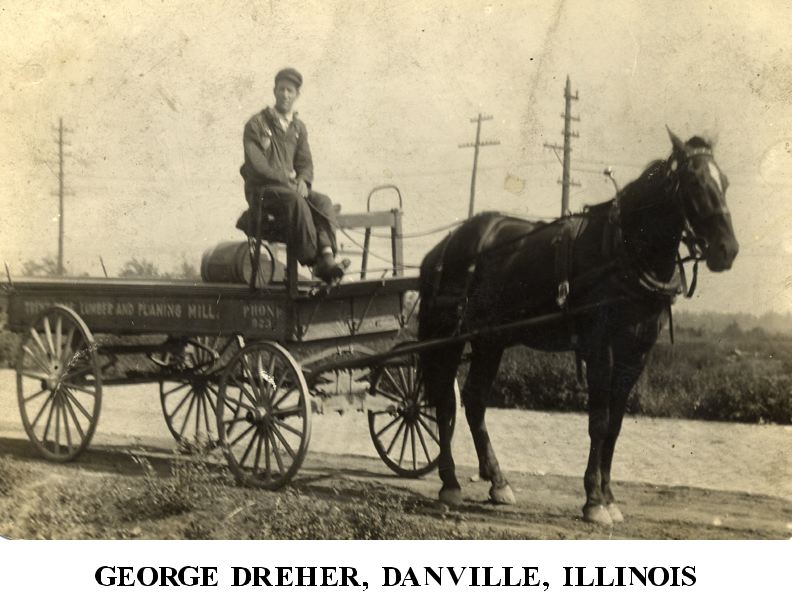

My grandfather George Edward Dreher was born on Sept. 19, 1893 and died on May 17, 1952. My grandmother Lena Gray Dreher was born on Aug. 13, 1892 and died on Dec. 16, 1946. My mother grew up on McKinley Avenue in Danville, Illinois. My mother’s family was hit hard by the great depression. Mom’s stories of her family’s survival during one of the most trying times of twentieth century America affected her children’s view of the world. Even during the great recovery after the end of WW2, my mother’s generation carried the scars of those years of struggle and sometimes near starvation. Everyone who is descended from the McKinley Avenue Dreher clan, carries the strength and determination of the strong women who gave birth to us, then raised us, nurtured us and showed us how to survive.

My great Grandfather, John Dreher was born in Nussplingen, Germany on February 15, 1861 the son of Joseph and Ursula Laffler Dreher. He immigrated to the U.S. and moved to Danville, Illinois in 1881 sponsored by an uncle, August Schatz. He had 4 brothers and 2 sisters. His brothers Engelbert, Fiedel, Martin and Joseph stayed in Germany. His sister Mary Elisabeth also stayed in Germany, but his sister Theresa came to Danville, Illinois and married Michael Yost. My great grandfather,John Dreher, married Mary Barbara Eberle in Peru, Indiana in October, 1884. My great grandmother, Mary Barbara Eberle was born in Peru, Indiana on December 3, 1863. She was the daughter of Jacob and Anna Marie Faust Eberle. Jacob Eberle was born in Germany February 27, 1825 and died in Peru, Indiana on January 30, 1887. Anna Marie Faust was born in Germany June 2, 1823 and died September 16, 1867 in Peru, Indiana. My great grandfather, John Dreher died January 6, 1934 in an automobile accident. My mother is Mary Lilian Dreher Starkey. Her parents were George and Lena Dreher and John Dreher was her grandfather.

NEW SALEM

Just beyond the New York Central tracks that crossed North Collett Street near Griggs, on the west side of Collett Street, I remember an old dilapidated building that resembled a saloon in a 1950s cowboy movie. Peering through dirty wavy glass windows, I could see broken remnants of the bar and tables and chairs covered with dust and cob webs. On a warm summer day, the saloon smelled like grandma’s attic. In front of the saloon near the curb was a hitching post for tying one’s horse. I was aware that most of my friends did not feel the connection to the past like I did. I used the smells and visuals as a conduit to a time and life I felt were more suited to my disposition. I knew inherently, that the fast paced world that was developing around me had the capacity to actually make me physically ill. Even as a preteen I understood that as a survival technique I had to find a way to live outside the expectations of that fast paced world. One way I escaped that world was to immerse myself in the study of the past. Most of that past in Danville led to one undeniable point in time when a young lawyer appeared on the scene, who would change the direction of our country and the world. His name was Abraham Lincoln.

When my parents took us to New Salem in Springfield, I’m sure their intent was to inspire us by exposing us to physical remnants of a very rich Illinois history. The scent of leather that had been drying up from over a century of exposure would be forever tattooed on my olfactory memory, ready to conjure up images of horses and buggies or leather bound books in a library lit by candle light. The clumping sound of shoe leather on hard roughly finished wooden floors painted the image of a strong woman cooking and baking over a black iron stove heated by burning wood. I envied them all for the fact that they had never known or been tempted by the things we later falsely classified as necessities. I envied the simplicity of their lives that I’m sure helped to balance the great struggles they endured. But I knew in many ways I had already been spoiled beyond redemption. I had already embraced many things they would never even dream possible.

I took my obsession with Lincoln to the point where I memorized the entire Gettysburg Address, which I can still recite today. As I read those words over and over again, they got under my skin, becoming a part of who I am. The words that made the biggest impression were these. “It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us -- that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion -- that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain -- that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom -- and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.” For me, even as a child, that’s what it meant to be an American. By his carefully chosen words, my hero and mentor had reached into the future to instruct me in my greatest duty as an American citizen.

Another hero and mentor as a young teen was D.H. Lawrence. “I am not a mechanism, an assembly of various sections. and it is not because the mechanism is working wrongly, that I am ill. I am ill because of wounds to the soul, to the deep emotional self, and the wounds to the soul take a long, long time, only time can help and patience, and a certain difficult repentance, realization of life’s mistake, and the freeing oneself from the endless repetition of the mistake which mankind at large has chosen to sanctify.” When I read these words they resonated with the core of my being. He had put into words what I felt and knew, but was unable to speak. I took D. H. Lawrence’s words and the words of Lincoln to heart, vowing to never be a conscious part of the “mistake which mankind at large has chosen to sanctify.”

REMEMBERING SUMMER

I remember the fragrance of lilacs in the spring. That was the smell of the end of a school year. I remember playing on the porch on a rainy summer day. Hugging the wall to avoid the spray carried on the wind. I remember the smell of a new mowed lawn, the sting of dust raised by a passing semi-truck, the taste of pink lemonade, the burn of bare feet on hot pavement, the sound of flip flops smacking my soles, the odor of chlorine on my skin, the warmth of sun after the rain.

I remember sitting on a tree limb eating cherries. I remember the taste of peach cobbler with homemade vanilla ice cream. I remember Kool aide served in sweaty aluminum glasses. I remember cherry cokes at the Germantown drug store. I remember collecting “pop” bottles to exchange for penny candy at Timm’s Grocery, I remember playing kick the can at dusk. I remember the sound of a hardball as it comes in contact with the bat. I remember fireflies and crickets.

I remember the humming sound of car wheels as they came in contact with the red bricks of Collett Street. I remember watermelon when they still had seeds. I remember the sound and smell of fireworks on the 4th of July. I remember the odor of lighter fluid mixed with hamburgers and hot dogs. I remember the sound of the ice-man, metal piercing the ice block as we children picked up the pieces to suck on. i remember the ice cream man, a huge music box on wheels, beckoning children.

I remember stock car races at the fairgrounds. I remember miniature golf, badminton, croquet and roller skating. I remember playing king of the mountain on the raft in the lake at the sportsman’s club. I remember Planters Peanuts and cream sodas at Lincoln Park. I remember the view from my father’s boat in the middle of Lake Vermilion. I remember summer nights before color TV and air-conditioning.

I remember stiff blue jeans and the smell of notebook paper. I remember the odor of crayons and paste. I remember wishing summer could last forever. But every summer eventually ended in going back to school. Then we set our sights on Thanksgiving and Christmas, hoping it was enough to get us through to the end of the year.

SNOW

When I was a child in Central Illinois, I loved snow. Even before I started school, before knowing the value of snow days, I loved the snow. I would stay out in spite of the caked ice on my knitted gloves that made my hands numb. I would continue to play with ten toes tingling under wet socks. I can remember the smell of snow in the air even before the first flake descended from heaven. I would race outside early on a snowy morning to enjoy the lily white drifts before they were soiled by the soot from nearby coal furnaces. I was tuned into the sound of a snowy night when snow plows could be heard in the distance, breaking an eerie silence. We built igloos and snowmen, fought snowball fights and charged down hillsides on our sleds, all in a race against that day when the sun would come out and erase the winter wonderland. Its fleeting existence made it so much more desirable. All the pain endured during a play day in the snow was mitigated by the experience of undressing in front of a steaming radiator that became a receptacle of our wet gloves and socks. Then off to the kitchen where mom had steaming hot cups of cocoa waiting with tiny marshmallows floating on top.

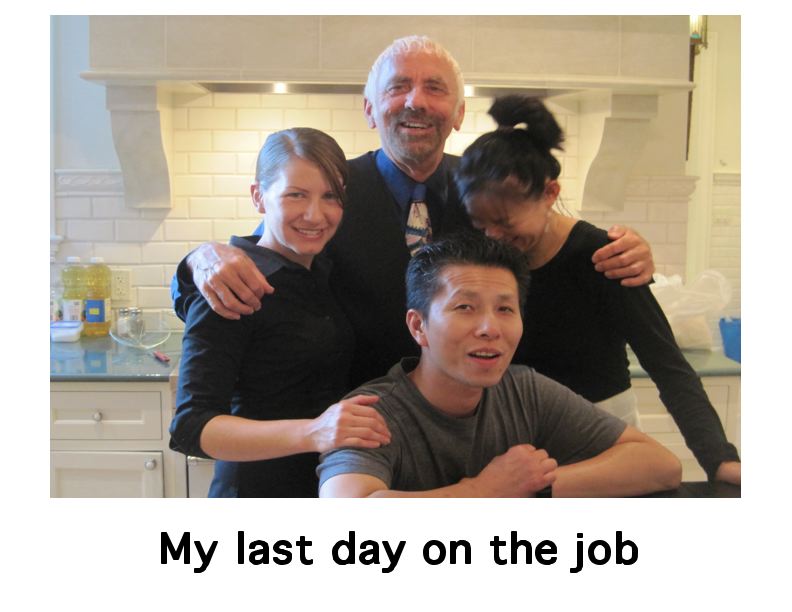

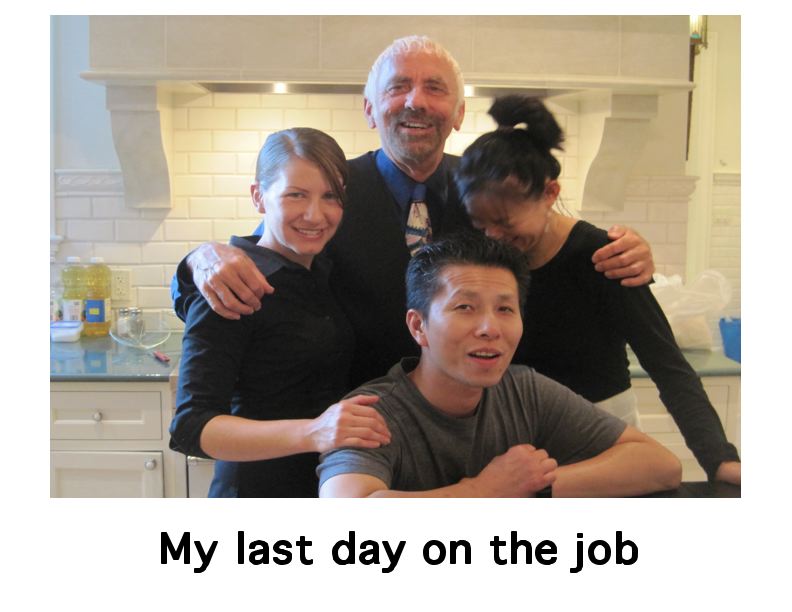

THE EXPLOSION