I was eight years old when my mother gave birth to her seventh child. This ended my position as the baby of the family. I remember very well the day my mother was due home from the hospital. I walked back and forth in front of the house waiting for the arrival of my new little sister. This was the first time I was so close to the process of birth. It was really the first time I had ever even contemplated it. Exactly one year and one month later in Belleville, New Jersey another birth took place which would have the most profound effect on my life. When I look back now, I can imagine that there was this great cosmic plan which connected all of these events. Two years following my sister birth, at the age of ten, I was confronted with the death of my best friend from grammar school who died during open heart surgery. That was the time in my life when I came to understand spirituality. I had been given, through my 10 years of life experiences, the picture of the cycle of life itself. There was no way at the time, to understand that my unique adolescent struggles would be a major factor in who I would become as an adult.

When my little sister first began to walk I can remember watching her on the sidewalk in front of our house on Collett Street. I was so afraid she would walk out into the street to be killed by a passing car, I never let my attention be distracted by anything else lest I be responsible for her death. I remember thinking “this must be what love feels like.” If you love someone, the worst thing that could happen is that they would die, I thought. I couldn't even entertain the idea in my head. The tears would stream down the front of my face at the very thought. From the experience of my school friend Sandy dying, I had a good idea of what it meant to have someone disappear from life. But as I mention her name now, sixty-three years later, I’ve learned that no one really disappears.

Chris and I developed a unique relationship. She was the first in the family to know that I am Gay. We had talked about the way other people perceive the world, knowing that it was not a perception we shared. We had created a language of our own, a code if you will, to describe our perspective. Chris and I divided the world into two groups of people, those who know and those who don't know. When I met Robby in 1980 I called my sister to tell her that I was in love. When she asked me to describe him I simply said, "he knows!" What we were talking about was consciousness. Rob was the my first life partner who shared my concept of how to live in the world in a conscious way. He and I developed our own code for knowing. We would see someone, smile at each other, then proclaim in unison, ”he's a dancer!" We were both beginning to understand that an undeniable connection exists between consciousness and creativity.

Rob and Bob’s first "spiritual experience" together happened on September 28, 1980 in Lafayette Park in San Francisco. Rob and I were both visiting San Francisco for the first time. We were meditating in the park in Pacific Heights, when we both had the same powerful premonition. This was the day Rob called his conception day. It was his parent's wedding anniversary and he was convinced it was the day he was conceived. On that foggy afternoon we both got the message that we should move to San Francisco. We understood there would be some great historical event that we needed to be part of. We both quietly acknowledged an uneasiness that accompanied this revelation. We quickly discounted the idea of an earthquake, "the big one", as it is known in the bay area. No, something was going to happen that had never happened before and it was our destiny to be a part of it. Of this we were both sure. We had been called, but for what, we had still to discover. But the calling was so strong we packed up all our belongings, along with our two dogs and moved to States Street in the Castro. We arrived on January 6, 1982.

We arrived in San Francisco on January 6, 1982. From our first moments in our new neighborhood we were aware that we were surrounded by people who "Know". We were amazed that we could have conversations with complete strangers about spiritual experiences without being labeled crazy. It was an environment where we could allow ourselves to open even more to seeing the wonderful things that existed all around us. It was in our ninth month in this new life that things really began to open to us. I had met a woman in her garden who told me she was going to die. She said that I would be with her at the moment of her death. I was in fact with her at the moment of her death nine months later. She gave both Rob and me a wealth of information about the world of seeing. Jiggs was in fact the one to tell us about that incredible historic event that we had come to San Francisco to be a part of. She told me that she was preparing me to care for many people who would die from AIDS. It was so early in the epidemic that even I found it difficult to believe.

Only some weeks earlier Rob and I had been reading a book by Jack Schwarz. Rob had developed a habit of reading aloud to me. We found ourselves almost in a trance state as the words Rob read resonated with our own lives. We were both paralyzed by what we felt now as we looked out of our States Street window onto the Castro district below us. There was a sense of impending doom. It was as though we were coming to grips with the reality of what was to transpire in the years to come, even though we had no idea of exactly what it looked like. When Jiggs made her prediction of the magnitude of AIDS, I could only partly hear the truth. The pieces of the puzzle were coming together in small bits which still allowed us the luxury of denial. My first friend died from AIDS just a few weeks before Jiggs died. It wasn't long after her death that we began to see people dying on States Street where we lived in the Castro.

Rob and I had adopted another idea from my relationship with my baby sister Chris. We had decided that since the world was in such a bad state, it would be to our advantage to do exactly the opposite of the accepted norm in most situations. Our motto was, "the opposite of everything is true!" In the beginning it was a joke in a way. We found that having this perspective was giving us a bigger view of choices in every situation though. We began to understand the difference between making a choice which really belonged to us and choices which were imposed upon us by other people’s expectations. The most important element was to understand that sometimes our choice was the same as the so called norm. As we practiced our lives in the “opposite is true” realm, it slowly peeled back the curtain on the wizard perpetuating the illusion.

When we began to be swallowed by the incredible amount of information and disinformation surrounding AIDS, Rob and I were adept in our alternative way of being in the world. We would not be in the line of guinea-pigs awaiting Western medicine's miracle cure. We decided instead to go beyond the fear of death and try to understand its place in our lives. When the HIV test was developed, we watched some of our friends die in spirit at the moment of being diagnosed positive. Rob and I decided that we would make informed changes in our health based on the assumption that we were positive, but would continue to live the other parts of our lives as though we were negative.

Rob began taking yoga classes with a man called Sequoia. The classes were designed for Gay men and taught in a house across the street from ours on States Street. This was a turning point in our life together. Rob enrolled in teacher training classes at the Iyenger Yoga Institute in San Francisco. When he began teaching special classes for people with AIDS in 1985 I became one of his students. We began seeing a homeopathic doctor and incorporated Chinese medicine, acupuncture and a vegetarian diet into our lifestyle. We both felt strong and healthy and clear in this time. In a way we were able to be in the middle of the epidemic without thinking that we were going to be the next ones to die. We began to take seminars with Steven Levine on death and dying. In San Francisco during this time, there was a mixture of fear and compassion, dedication and searching. We were searching inside ourselves for a way to understand the world from an organic point of view. The practice of yoga was the catalyst which sent us both soaring into our new way of life. Rob's understanding of the human body combined with my ability to put experiences into words made for a great team effort.

We bought meditation tapes and attended seminars and workshops with people who had similar experiences. A foundation had already been laid in San Francisco for the acceptance of such things. The willingness to explore the mysteries of life in the face of death made our task simple. We were finding, in the middle of western culture, a very eastern, third world way of seeing. Rob and I often joked in later years that we had already had the India experience of death in San Francisco. It was impossible to face so many deaths of friends without being dramatically changed forever. It was our task to direct that change in a positive beneficial way for ourselves and others.

Because of the epidemic, we realized there was a subconscious connection between sex and death. It was a difficult problem to heal in the shadow of vicious right-wing attacks telling us we deserved to die. The important thing in this time became the physical contact through yoga. We were working with people who needed to be touched, who had been shunned because of irrational fear. This we realized was important for the students with AIDS as well as for ourselves. As there is always a silver lining in every bad situation, the good thing which came out of this time was a better perspective on true intimacy. Within a community that had been separated from the rest of the world because of sexuality, it was difficult to see beyond the sex. Rob was proud of my accomplishments in the yoga classes and I was elated at his ability to be the teacher/father figure. We came through this difficult time together with a strengthened bond that would give us courage and direction to survive the end of the 1980s decade.

On Sunday, October 7, 1984, our neighbor Frank Lobraico died from complications related to AIDS. Frank and his husband John Krause were to Rob and me, the epitome of the San Francisco Gay couple. We saw them our first days on States Street as a representation of what we were or could become. Like all new arrivals to San Francisco, a careful examination of our histories revealed that Frank and I may have been at the University of Illinois at the same time, he as an architecture student and I as an employee. Frank’s totally renovated, modernized Victorian house fascinated Rob so much that he drew it with colored pencils. Our first two years in San Francisco were as magical and uplifting as we had imagined.

But then one of our role models was dead, so we wondered if this was also our fate as a San Francisco Gay couple. The epidemic was becoming too real now. It was changing our lives in very dramatic ways. We began to equate intimacy with death, sometimes finding it difficult to even be intimate with each other. Each time we got the slightest scar or blemish on our skin we would have the other looking to see if perhaps it was the first sign of a skin lesion. There seemed to be no way out, we thought. We were all going to die in the next ten years and in a way it seemed the ones who died first were the lucky ones. At least they wouldn't have to endure the horror of watching everyone else die slow painful deaths.

At the end of November we attended a celebration of Frank's life at the amphitheater near the top of Mount Tamalpais in Marin County. Frank and John designed the sets and lighting for the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus. I knew the celebration would be special, given the incredible talent of their friends. But I had no idea nature, or perhaps the spirits of the indigenous people buried nearby would also take part.

When we arrived it was cold and foggy so we huddled together on the benches to keep warm. As we entered the amphitheater we had all been given silver helium balloons attached to silver ribbons. We were instructed to release the balloons on cue, as a symbol of releasing Frank's spirit. As the silver balloons rose above the amphitheater, the fog rose with them, allowing the morning sun to stream onto the celebration. I was overcome with emotion at this spectacular synchronicity with nature. But it was only the beginning of a new world defined by the intimate relationship we all had with death. Our ability to see and create magic would be repeated over and over again in the months and years to come. We all now stood in a place where we could gaze beyond the dense physical world into the world of spirit, where we would all return one day.”

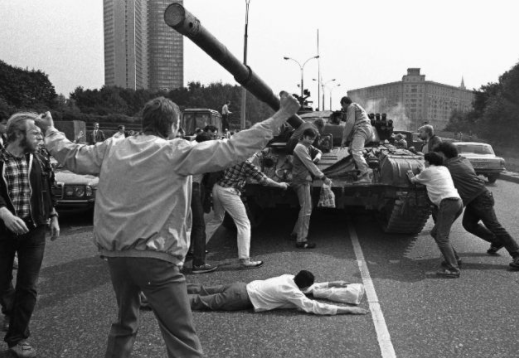

By 1989 living in the Castro was like being in a war zone. It was not uncommon to talk to people who had already lost more than 100 friends and acquaintances to AIDS. Two of the most important issues were becoming the care and the mental health of survivors.

On January 5, 1989, a neighbor on States Street died. Within two months, another man from the same house would die. On June 17 and July 17, just two houses further up the street, Mike and Fred would die just one month apart. They had been together for decades. On June 1, in the same house where Frank and John had lived, Rick died. His lover would die some months later. On October 22, Steve from the house directly behind us died. This was life in San Francisco's Castro District in 1989. Through the rest of 1989, I said good-bye to Stephen, Gary, Terry, Chasen, James, Schell, David, Jeff, Gabriele, Ricky, Joe, Nick, Joseph, Larry, Doug, and Max. I had become one of the war casualties. I had lost my endurance and my strength. I admitted for the first time that I couldn't last much longer with things as they were. I needed a rest and I needed to cry. For five years I went from one death to another with no time to grieve or heal. Crying wasn't a luxury I afforded myself then. I was afraid if I started I would never stop.

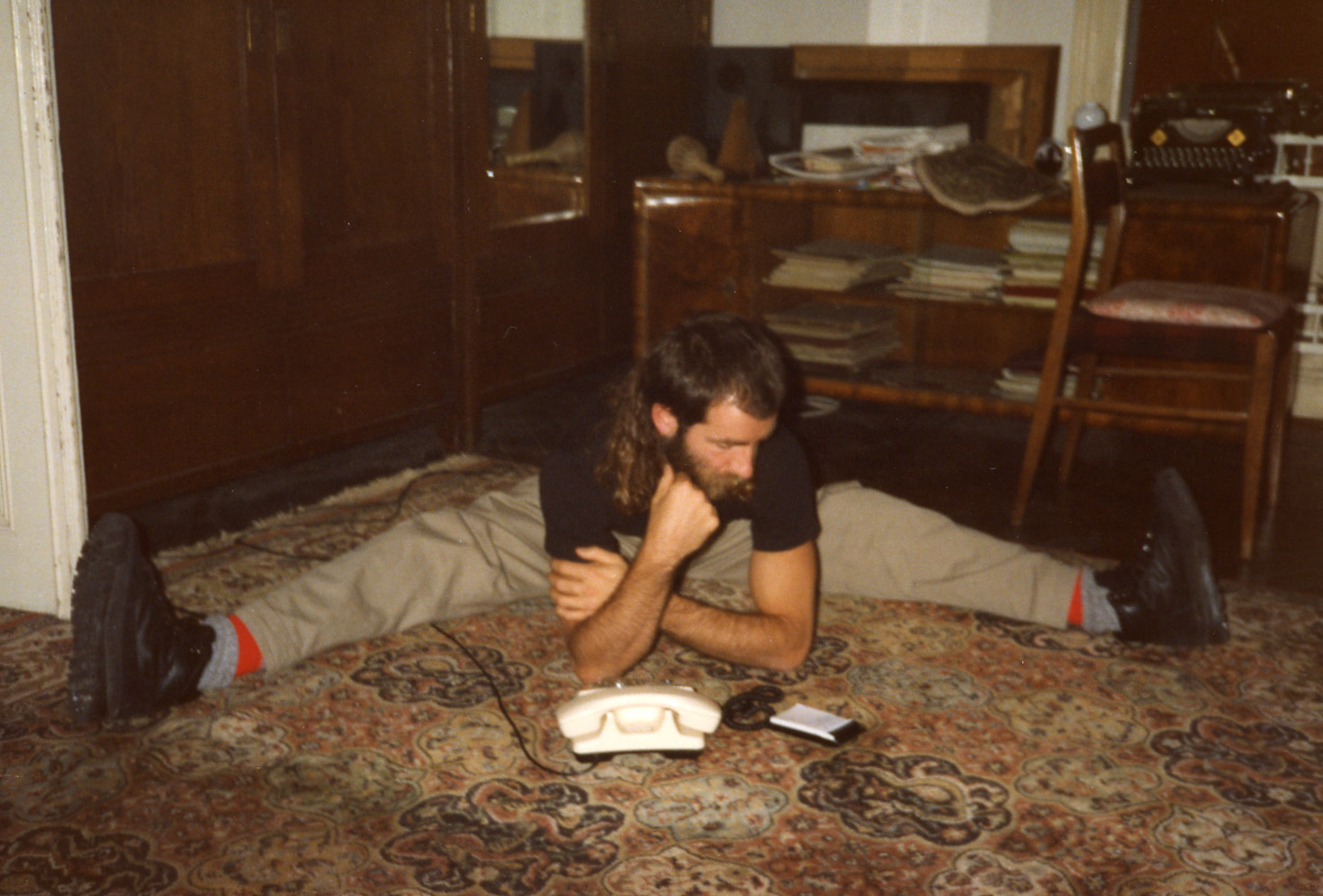

On New Year’s Day 1990, we saw a new decade as a marker for change. We had lived through seven years of relentless death, grief and emotional turmoil. Rob and I agreed we needed to shake things up if we were going to survive. In the late spring Rob decided to improve his yoga teaching skills by doing a ten day intensive workshop on the Greek island of Lesbos. At the end of the workshop he was invited to spend a week in Berlin. When he called me from a payphone near the remnants of the Berlin Wall, he was in tears. “We have to sell everything we own and move to Berlin! Berlin is the center of the universe right now! For the first time in years I feel hope instead of grief!”

I didn’t even hesitate before responding to Rob’s demand. “Yes, let’s sell everything we own and move to Berlin!”

We had just survived a war. Everything in our lives moving forward would take place in the shadow of that conflict. We had endured suffering that most people would consider unimaginable. But even on the worst days, the thing that kept us going was love. Our love for San Francisco and the love of our friends and neighbors. We had come to the city by the bay in order to create a family of choice. When our family was suffering, we had to stay to help in any way we could. But in the summer of 1990, our physical and mental health took center stage. We had reached the end of the rope. We needed to go somewhere, anywhere, where no one was dying. Too many in our family of choice had died. When we walked the streets we saw ghosts. Every building, every park, every street contained the memory of someone we loved, who was no longer with us.

In the spring of 1991, we boarded a Pan Am flight to Berlin. We felt invincible. After what we had been through in San Francisco, we felt there was nothing in the world we couldn’t handle. We were practicing Rob’s yoga class metaphor for letting go. Just close your eyes, hold your nose, then jump into the water knowing that everything will be okay.

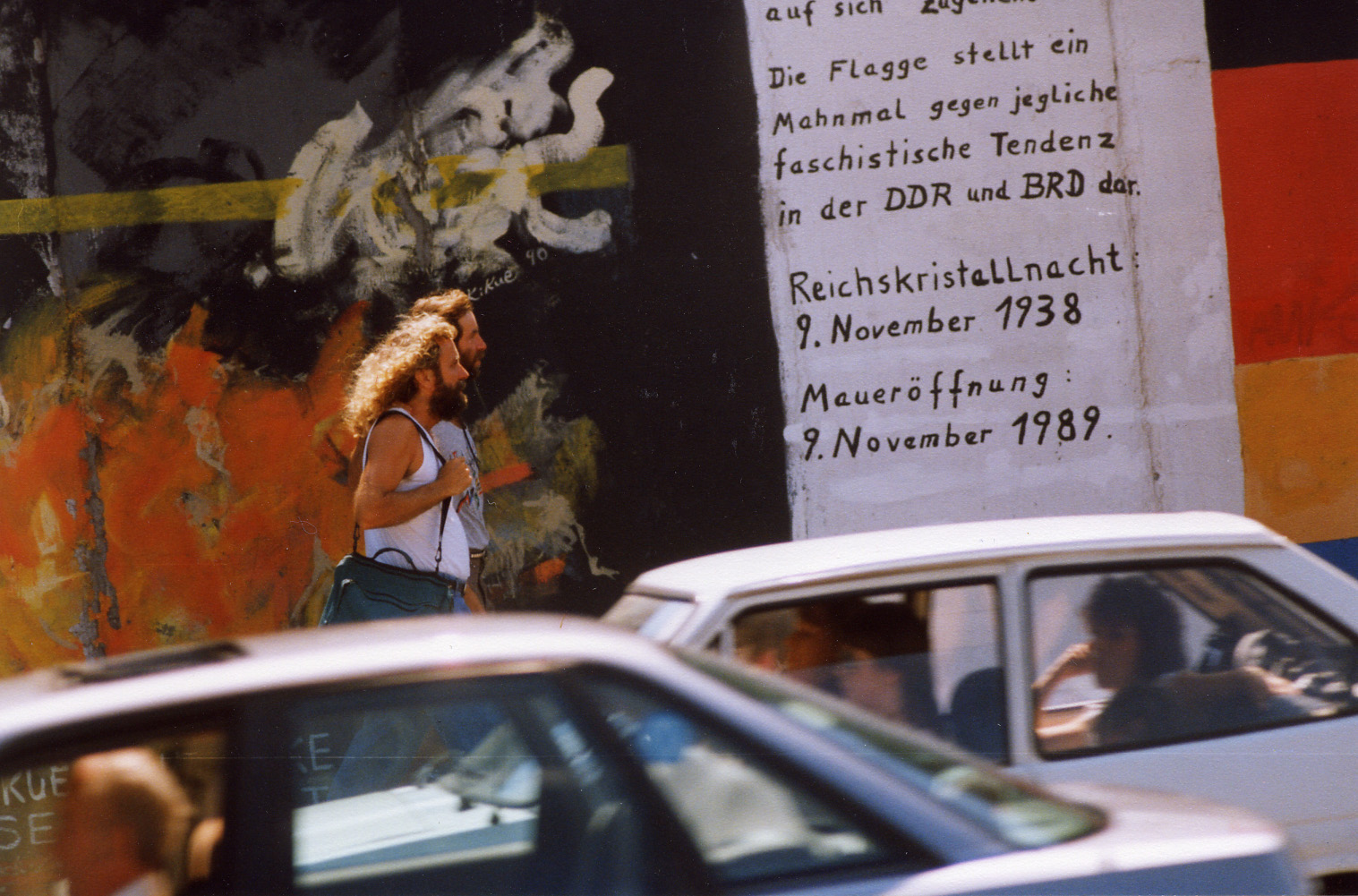

When Rob called from Berlin in the summer of 1990, describing it as the center of the universe, he was exactly right. It was the antithesis of the life we had left behind in San Francisco. There was hope everywhere. A curtain had been torn down, revealing the absurdities of many of the human constructed dysfunctions that plagued our world. A short walk across a bridge from West Berlin to East Berlin, was like a walk back in time. One side had evolved for 40 years, while the other had stood still. But everyone living in those days of wonder and revelation shared one obvious concern. We were living in a dream that we would soon have to wake up from. There was no way such a utopian existence would be allowed to continue. The people were energized by an act of bloodless revolution. Everyone had incredible stories to tell, of the night the Wall came down. But those in power on both sides of that revolution were plotting how to take back the power they had lost. We all knew, intuitively, that our privilege of experiencing this accidental tear in the fabric of time, would be short lived.

From Rob's Journal, June 27, 1991

"... to move into a journey in Unknown, to reveal more that is hidden inside. If Bob and I had thus far survived the onslaught of AIDS, my quiet time on Lesbos whispered to me that it is not good enough to simply be living, that one must be alive and to share and to appreciate and to celebrate life. The answer to my question, 'why am I still alive, when so many friends have already died?' was simple, and I was encouraged to leap further and deeper than I ever had before..."

"So we sit perched between two worlds, vastly different, one, recently described to me as the seat of the masculine, the active, outward, capitalistic West; and the counterpart, the feminine, internal feeling East. And the wall, the subtle membrane dividing right hemisphere from left has been dissolved. And now the tumultuous, timely integration has begun. But like all unions, the task at hand is not an easy one. And we feel the pain, the animosities, the difficulties of 'jaded' Westerners, who are called upon to accept and integrate the naive, fragile, unsophisticated Easterners into their world. Berlin is a fascinating place and I am so fortunate to be living here..."

"... a veritable Tower of Babel is this world!... the truth is that verbal communication is secondary to a truer language of heartfelt communication.”

It was possible for us to taste the flavor of both worlds before the unbelievable effort began in the summer of 1991, to bring the two worlds together as one. In our effort to understand ourselves and our place in this complicated world, we could not have chosen a better place to begin our journey. In the spring and summer of 1991, Berlin was without a doubt the center of the universe.

Rob and I spent the first weeks in Berlin living with an Irish yoga teacher Rob had met on the island of Lesbos the summer before. Camilla O'Callaghan lived in a group house in Kreuzberg, Berlin's Bohemian neighborhood. As we walked across the Warschauerbrücke, a bridge which had once been a checkpoint between the East and West, we had the distinct feeling that we were entering the old DDR. The energy of forty years of oppressive control had not disappeared overnight with the fall of the wall. Camilla suggested that we might want to consider the possibility of squatting in an abandoned East Berlin building since we did not have an unlimited supply of money. The idea was out of the question with Rob and me. We struggled enough adjusting to an extremely different environment without calling undue attention to ourselves. We still had quite a bit of our American upbringing to peel away.

We found a student apartment to rent for ten weeks for $400. It was a small one room apartment with a kitchen and toilet. The shower was in the kitchen but was not connected to a water supply. We had to heat water in a small heater above the sink, pour it into a bucket with some cold water and then shower by pouring small amounts of water over the head with a cup. It was a challenge, but was more than offset by the fact that we had privacy in our own apartment. At the end of the ten weeks, Elke, the girlfriend of our student landlord arranged for us to care for two apartments in a squat building in East Berlin's Mitte. It was our job to look after the plants and bring in the mail while the occupiers were on their first post wall holiday. Rob told our other Berliner friends that we were sub-squatting. We referred to it as our besetzteshaus on Ackerstrasse.

On the morning of August 12, 1991 we received a large package from our friend Gary in San Francisco. It was filled with newspaper articles and a long letter filling in all the details of life in San Francisco without Rob and Bob. We spread the newspaper articles over the floor in Rob's apartment and were reading to each other. Smelling smoke, I checked to see if Rob had left something cooking. After checking the kitchen I returned to reading the newspapers when I found everything in order. A few minutes later we were disturbed by loud footsteps in the hallway, then someone banging on the door yelling, "Feuer, Raus!" Then we heard Elke yelling from the hallway above, "Rob, Bob get out, the building is on fire!”

I ran down to my apartment one floor below, grabbing my backpack with all of my manuscripts. As I lifted the bag it opened spilling all of my papers onto the floor. Looking out into the courtyard through the window I could see large pieces of burning wood falling in front of the window. I quickly packed the papers back into the bag, then ran through the courtyard dodging the falling burning debris. As I entered the street, I turned back toward the building, watching flames and smoke billowing into the sky. I searched for Rob in the crowd, but could not find him. I found Elke who told me that Rob had not come out. I went into hysterics, trying to run back into the building, but was held back by the firefighters.

My head was spinning as I tried to imagine what I would do if anything happened to my Robby. It's amazing how many things you can process through your brain in a moment of panic. Then I saw him emerge through the entrance escorted by two firemen. He was carrying everything he owned neatly packed into his bags. He had been at the back of the building where he could not see the smoke and flames. He had been unaware that the only way out would become completely blocked just minutes after he came out into the street. It is only in hindsight that I realized how traumatized I was in those moments before Rob emerged from the burning building.

Rob's Journal

"I stay slightly longer, refusing for the few worldly possessions I own anyway to go up in flames while Bob panics since I didn't follow him downstairs. ('Oh no! not my new Birkenstocks, my new lederhosen shorts, not to fire!' think I) Was I freaked when I reached the courtyard and falling beams of wood on fire."

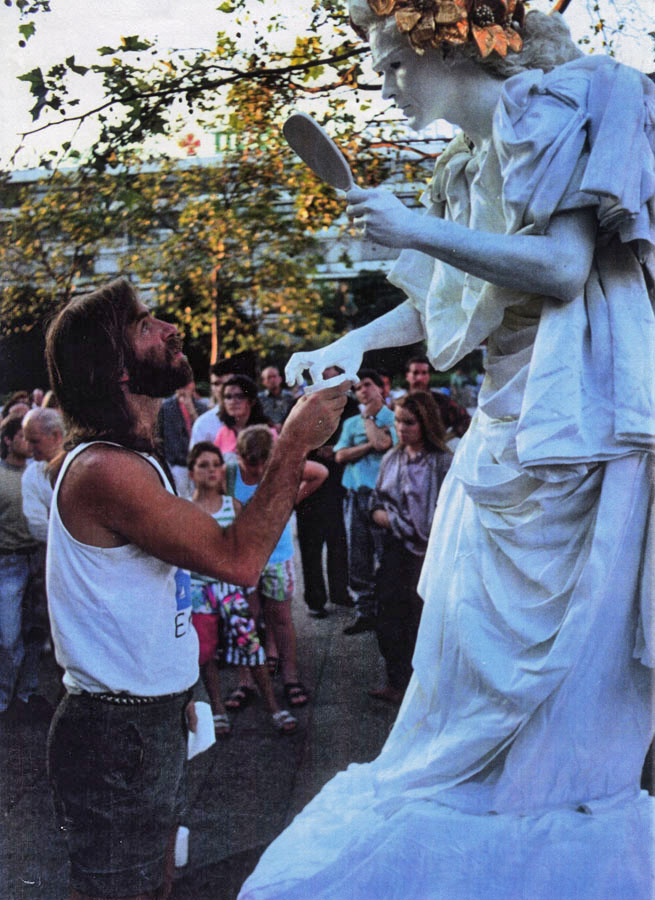

Our life in Berlin in 1991 was lived in an alternate plane where truth had become so transparent it was accepted without challenge. The impulse to deny truth did not exist there, because everyone shared the excitement of being at the literal center of the universe. The end of 40 years of oppression had created a portal, a virtual tear in the fabric of externally imposed realities. There was a palpable sense of total freedom. Everything about accepted cultural norms now seemed absurd. A radiant light shone through the open wall that once separated two opposing lies, washing away everyone’s fear of non-conforming. That light of truth shone round the world, beckoning those who were prepared to embrace it. Rob and I had been called to Berlin from San Francisco. Marcylio had been called from the Amazonian rain forests of Brazil. In our first meeting in Breitscheidplatz on the Kurfürstendamm, we all recognized each other immediately.

Marcylio told us he had come to Berlin to bring sunshine to the people of Germany. He was a street performer who dressed himself as a statue, standing on a pedestal, above the passersby on the Kurfürstendamm. His performance was in fact his ability to “not perform.” Marcylio was able to stand motionless for up to five hours at a time, with only a couple of brief breaks. To the unaware, Marcylio standing still in white clown makeup, wig and toga like costume seemed absolutely absurd, ridiculous, “not performing at all,” - creating an uneasiness and bewilderment at why some people would contribute money to such a ridiculous unsatisfying show. But to the sensitive, there was an immediate recognition of the highly disciplined nature of “not doing,” of letting go, of standing peacefully amidst thousands of distracted (and sometimes disturbed) passersby. What Rob and I understood was that Marcylio was in trance.

Marcylio invited Rob to assist him in his performances. Of course Rob accepted. Rob the yoga teacher and Marcylio the Brazilian Shaman, standing together in the center of the universe, together supporting the silent dynamic of inner peace, creating a juxtaposition of ways of being, strong, silent, internal on one hand, in contrast to the outward directed energy of the masses. This was an example of three people’s lives converging because we were following our true spirit paths. We had the ability to recognize each other because we were all free of external burdens. We had all responded to the call of the universe, to come to this place that had seen one of the most tragic, horrific examples of the human spirit gone bad, just 46 years before. And now, for a brief moment it had become a place of celebration, of positive light streaming through a tiny tear in the fabric of man-made suffering. Would this be the opportunity for mankind to redeem itself, or was the next holocaust just around the corner? Only time would tell.

Marcylio traveled with a group of Brazilians who performed Capoeira dance in the evenings. He joked that he had come to Berlin and Germany to help them heal. He would do it with color and rainbows from the rain forest, he said! Marcylio had a spirit that could only be described as shamanic. If he put his warm hand upon someone’s shoulder, they would be jolted by the energy that transferred from his body to theirs. It was the same with the dancing in the evenings. There was always a magical and transformative energy that shined in contrast to the old Germany. But in the summer of 1991, Berlin had become a portal to a new world, a place where people had simply stood together holding hands, while they challenged the old paradigm by simple saying “NO!”

I met Joachim at the Brandenburg Gate in the spring of 1991. It was late and there were few people around. I’m sure Joachim sensed my feelings of wonder, because he approached me with a question. “Were you here on the night it came down?” No, I said. When I told him I watched on CNN from San Francisco, his eyes lit up. “So you’re from San Francisco! Well, let me tell you about that night!”

Joachim had possibly been one of the people standing on the wall in that iconic Brandenburg Gate news photo I saw on CNN. His husband Ulf had escaped East Germany the year before. I came to the Brandenburg Gate that night because I felt the need to stand at the virtual center of the universe. On that night, on that very spot, the universe provided a link that makes me look back wondering, “what would my life have been if I had never met Joachim?”

The four of us became close very quickly. Joachim was obsessed with showing us everything directly related to the fall of the wall. Ulf provided the East German, East Berlin perspective. When Joachim discovered I was showering by pouring water over my head with a cup, he gave us a key to the apartment so we could shower properly. When Rob and Bob were forced out of their East Berlin flats because of fire, that key provided the momentary shelter we needed, but there we stayed for the rest of our time in Berlin.

Ulf was from Frankfurt Oder, on the border of Poland. He told us of his relentless struggle to escape the East. On a camping trip to Romania, to plan a river crossing escape, he had to turn back because his East German Marks were worthless. There was simply nothing to buy. The shelves were empty. At a rest stop on the Autobahn through East Germany, Ulf was allowed to visit with his parents. He slipped them some music CDs. Unfortunately his mom made the mistake of thanking him for them over the phone. Within an hour the STASI was at the front door demanding they surrender the CDs. But Ulf’s most fascinating story is about how he finally escaped to the West.

Ulf met a British man who was visiting East Berlin on a day pass. That is when they hatched their plan. They exchanged contact information and the game began. Ulf went to immigration authorities requesting permission to leave in order to marry his British boyfriend. Of course his request was immediately denied. But Ulf didn’t give up. He went back again and again, designing outfits with subtle but noticeable flair for each visit. They finally provided an exit visa based on mental health issues.

Well, Ulf was not done with them. On walks through West Berlin, whenever he passed a checkpoint he would taunt the guards. Then he devised a way to do his laundry cheaper, not really to save money, but just to prove he could. With his West German passport he would get a day pass, then take a suitcase full of dirty laundry to the laundromat near where he had lived. Then he would bring the clean laundry back to the west. It was Ulf’s way of proving the system that oppressed him was a joke!

Traveling through Berlin with Ulf was a fascinating lesson in history. His obsession for escape made him an accidental documentarian. We took a tour of the East Berlin U-Bahn stations where Ulf pointed out all the stairways that were meticulously concealed by the Russians during their occupation. West Berlin trains would pass through dark station below, as soldiers with machine guns occasionally blurred their peripheral vision.

Gesine was Ulf and Joachim’s best friend, so of course she became part of this growing family. Gesine’s family’s property had been confiscated during the Russian occupation and had now been returned to Gesine. She could not bear the thought of throwing people out of their long term home, so she built a small summer cottage on the back of the property and allowed the tenants to stay.

The drive to Gesine’s summer cottage was fascinating. We drove down a small country dirt road to a narrow river where a man waited with a small barge. Once we drove onto the barge, the man pulled us across to the other side by hand, with a pulley that straddled the river between two poles. I was positive I was witnessing something that would soon be destroyed forever. I was feeling something most people in the west were blinded to, but many people in East Germany watched with fear. They told me often, “we didn’t fight for capitalism, we fought for freedom.” For me personally, that man pulling us across the river represented a meditation, a man who woke up everyday with a purpose. The image of that trip across the river is etched on my mind like a sooting fine expressionist painting of a time that no longer exists.

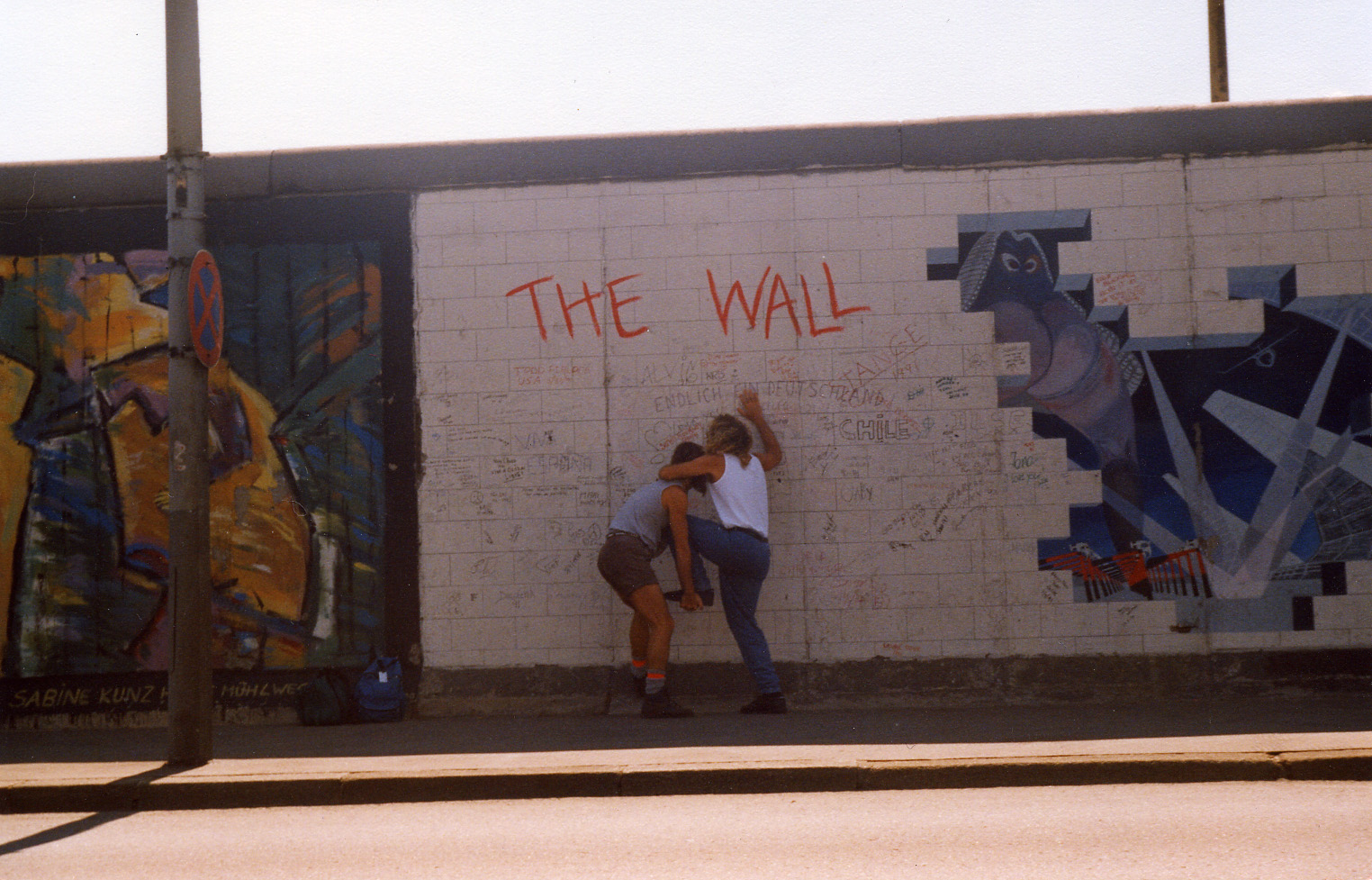

Berlin, April 1991

Today is the first time I have seen the Berlin Wall. To actually physically touch it is such an exhilarating experience. My body is consumed with the memories of fear and death, struggle and hope, tears of pain and joy all mixed into the concrete together. The line that was drawn more than forty years ago between the East and the West is evident in the void created between the two sides of the wall. As I walk through this area once known as no-man’s-land there is a sense of miraculous wonder, as if the fear of being shot is still hanging in the air, waiting to be blown away by the winds of time. The physical scars left upon the buildings and the land are symbols of what it has meant to the people’s personal lives. They are cut in half with one half on the East and the other half precariously dangling over the West. I have the sense that I am participating in something of extremely important great historic significance. I also have the fear that it will all somehow be erased forever.

In my heart I can feel the sense of urgency to experience this to the fullest, to take notes, to save the experiences for future generations. There is a movement among some Germans to bury it all beneath unmarked tombstones disguised as high-rise office buildings, apartments, and parks. I mourn the loss of the memory of what was good about the East. I fear it will all be erased in a revisionist history book that paints everything in a black and white, good and evil plot. As I walk into the East I have a sense of walking backwards in time. There are no electric signs, few telephones, no billboards, but an incredible sense of simplicity.

Our first days in Berlin are in the Bohemian neighborhood, Kreuzberg. We live with Camilla O'Callaghan, an Irish yoga teacher Rob had met on Lesbos. The flat is above a Turkish bakery and produce market. The steps that lead up to the third floor sag in the middle as if a million boots have worn them down over a century of wear. Everything looks old and dirty. I was surprised at my indifference to the imperfection. The dirt and the imperfection are all necessary to the ambiance, the old world charm.

We are just a few minutes walk from Warschauerbrücke, a bridge which had once been a checkpoint between the East and West. I remember feeling fear about crossing the bridge, but I was aware that giving into that emotion was not an option. I preferred to see it as excitement. I walked through the fear and came out in a place that filled me with the wonder of a child. Every step I took was with the knowledge that I was participating in an historical event. We walked across the Warschauerbrücke at dusk, leaving the lights of West Berlin behind us. The streets of East Berlin were dark, but without threat. As Camilla led us through the deserted streets I had the feeling we were in the Berlin after the allied bombing in 1945. We came to a building that looked as if it had taken a direct hit. People were standing in the street outside. There was loud music coming from the first floor. Inside was a disco that had been constructed just days before. These were common after the wall came down. They would continue until someone came to tell them they had to stop. It was a kind of anarchy that had filled the void left with the collapse of the DDR. We were all children playing in the absence of adult supervision. We savored every moment with the knowledge that it could all be taken away im einen Augenblick (in the blink of an eye). It was a time and experience that would never come again.

On the Berlin U-Bahn (subway) map you can see the Berlin Wall represented by a broken line. Our apartment is one block from the Schlesisches Tor station at the end of the number one line, represented by a green line on the map (below center, right side of the map). We live in a neighborhood that was surrounded by the Wall on three sides. Before the separation of Germany, Schlesisches Tor was a station on the line to Warschauer Strasse. In 1991 the tracks end in mid air as if they had been severed by a great knife that cut the city into pieces like a cake. To the west of the apartment was Görlitzer Bahnhof station where a park had been constructed on the grounds of the former site of a major railway station that led to the East. The railway bridge still crossed the river and was another major link that was heavily protected during the days of the Wall. The most interesting thing about a neighborhood like Kreuzberg was that everyone had an interesting story about life with the Wall!

Some day, decades from now, when I read my notes I hope I can remember the feelings I now have inside my heart. It’s a good idea to keep a journal that chronicles all the times and physical events that compose this magical journey. But they will be useless if I forget the spirit in which this journey is traveled.

For the first time in my life I am the foreigner (Ausländer). I cannot walk out the door onto the street with one ounce of confidence that there will be anyone who understands “where I’m coming from.” It's a humbling experience to be forced to face who you are and what you truly believe, without the chorus of one’s fellow citizens keeping you on the “right course.” The most freeing aspect of being a foreigner is the lack of expectations from those around you. If I do something absolutely outrageous, no one will notice. The Germans will simply look at me assuming that’s probably the way they do it in America. The thing I feel the most is the responsibility required with total freedom. With no one looking over my shoulder I have to set my own boundaries. I am unsettled by the recognition of how many of my ideas and actions were not mine at all. I was simply doing what was expected of me as an American. I have this incredible fear that I will return to America and my own people will hate me. What will they think when I tell them there are places in the world that in some ways offer more freedom than my birthplace?

In my minds eye, my time in Berlin is like a dream. I knew I was experiencing something that would never be duplicated. There was a feeling of connectedness that usually exists after a natural disaster, but this was no disaster, it was a miracle. In the summer of 1991, I came to Berlin with a decade of grief on my shoulders. Berlin allowed me to look at that grief from a distance, from a new perspective. Nobody died that summer, and if they did I didn’t hear about. That’s all I needed in order to heal. For the first time in a long time I could see a future ahead of me. For the first time in a long time, I no longer believed I was going to die too. But there was another part of the healing that was totally unexpected. I had to admit that without the AIDS experience in San Francisco, I would never have sold everything and moved to Europe. The experience of the 1980s in San Francisco had shaped my character in a dramatic way. I was no longer afraid of death. I had watched too many on their death beds regretting the things they hadn’t done. That opened the door to something that looked like courage, but wasn’t really. I believe it would have taken more courage to stay in San Francisco one more year.

On a beautiful warm spring day we decided to take a stroll across the Görlitzer bridge to Treptower park. We sat upon a blanket for a traditional picnic lunch. It could have been my hometown Danville in 1956. I felt extremely lucky to be participating in an experiment that we all knew would soon vanish forever from the realm of possibilities. I couldn’t help but notice everyone staring at us as they passed by on a nearby path. As casually dressed as we were we still stood out because everything we owned was from the West. After lunch we went to ride a ferris wheel. From the top Rob and I got the first glimpse of Berlin from the perspective of the East Berliners. Even five months after the reunification we could still see the outline of the wall. There was a stark contrast between the tree lined streets of the West and the barren “no man’s land” that buffered the Wall. The landscape looked as though two very different artists with two very different ideas of style had shared opposite halves of the same canvas.

The summer before, the Ostmark, or East German Mark had been eliminated. Prices in the East were still much lower than in the West. I wondered how they would ever be able to bring them to parity. On our subsequent trips to the East I began to feel empathy and recognize an affinity with the East Germans. That recognition of my childhood during our picnic in an East Berlin park stirred up a lot of memories of what had been eliminated from my own life as I had watched the world change around me. In the presence of the great experiment of reuniting two cultures separated for 40 years, I was given the privilege of seeing both cultures very clearly.

One thing both East and West Germans agreed upon was that the American perspective of their great experiment was extremely flawed! Both had lived with the Wall for four decades and understood the intricacies and nuances of a divided society. Both were quick to point out that they were the ones who brought the Wall down, not Reagan! The most revealing aspect for myself came through the stories of what the East Germans wanted, what they had longed for those forty years behind the wall. It was not the black and white, simplistic Cold War fairy tale offered by American network newscasts. What they wanted was the right to choose their own lives.

In the summer of 1991, the name Berlin could not be spoken without the word Wall being subconsciously added. Living in Berlin then, was an exercise in self-examination. How would you act if there were no rules? It was a short period where we could act out our fantasies like children in an abandoned field, creating an imaginary world with whatever debris was left behind.

Near our home in Kreuzberg a couple had commandeered an abandoned watchtower near the wall, turning it into a coffee shop. On the streets of East Berlin, basements were turned into “speakeasy” type clubs, with local bands performing. On the sidewalks of the Kurfürstendamm, recent arrivals from the east laid out their wares on collapsable tables that they could quickly break down as they escaped the police. There were questionable pieces of the wall for sale, as well as varied versions of Russian Matryoshka stacking dolls.

For a while Rob was staying in East Berlin while I was living in Wedding in the west. Before we separated for the night, we had to plan our morning rendezvous because there were no phones in the east. On the west side, the place to be was Breitscheid Platz, beneath the ruins of the Gedächtniskirche. In the east the place to be was Alexanderplatz. In Alexanderplatz we encountered what we called “ the lost soldiers.” Hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops were trapped in limbo, while the former Soviet Union tried to incorporate them back into Russia. They wandered the streets in uniform, with nothing to do, with no authority, among people they had once oppressed with authoritarian laws. It was miraculous, how they were then accepted as part of the scenery, as a statement on the bloodless revolution that had stopped the world.

I was touched by the stories of the East Germans. As an American, I too had believed in the fairy tale of a desperate people behind the “iron curtain” longing to go shopping. That image was bolstered by the coverage of East Germans filing through West Berlin department stores in awe of the abundance and assortment of goods for sale. As we had watched CNN from American living rooms we saw the East Germans as reflections of ourselves. We imagined what they were saying and what they would feel and believe based on our perspectives from our own lives.

I found myself in a personal crisis as I listened to the East Germans tell their own stories. They threatened everything I had believed growing up in America. Had I been listening to their stories in the comfort of an American living room, I might have been able to brush it off casually. If my own life was not being turned upside-down with the extremely personal transformational act of living in Berlin, I might have been able to avoid the great awakening of my consciousness. I was put in the difficult position of admitting that the culture I grew up in was only a tiny fraction of a vast world of diversity and differing opinions. I was forced to admit that the black and white lines we Americans drew between right and wrong were really vague lines of ignorance that could quickly be erased with the right experience and information.

There was one thing East Germans longed to buy more than anything else after the Wall came down. Bananas! In the months after the Wall was opened it was impossible to find bananas in West Germany. The thing East Germans wanted the most during those forty years of isolation was freedom! Freedom to think for themselves, freedom to move about without restrictions, freedom from fear of reprisals from a totalitarian government, freedom of religion.

The difficult and surprising thing for people in the West to hear and understand was the idea that there were things the East Germans liked about their lives. They liked job security, universal health care and the sense of community that comes from a culture devoid of “extreme” capitalism. Like it or not, a totalitarian state like the oppressive East German DDR created a place where family and personal relationships were the most important thing. For me, as an American and a Westerner, I was forced to admit to myself that I longed for what they had in that realm. The East Germans knew that part of their lives would be destroyed by the kind of extreme materialism that had separated them from their West German counterparts. I mourned with them in this knowledge, because they were able to take me, as an adult, on a personal journey back to my childhood in the Central Illinois of the 1950s, before we had lost that connection ourselves.

This morning we awoke to the news of an attempted coup in the Soviet Union. We are glued to the TV, watching the events unfold on CNN. Suddenly those Russian soldiers in East Berlin don’t seem so harmless anymore. Here in Berlin it seems we are in the middle of everything that’s happening. I have lost my innocence! No need for Germans to accuse me of being a naïve American any longer. I have been educated in these past few months. I remember how threatening it seemed when Camilla suggested we live in an East Berlin besetzteshaus. That first night crossing Warschauer Brücke into the darkness of East Berlin seems so distant now. In just a few months they have been able to illuminate the darkness with neon signs glaring from sparkling new Western style shops. Perhaps they wanted to change it quickly so a coup would be less likely to succeed. Now that it has been “Westernized” my fear has been replaced with sadness, as though something valuable is being lost. I long for those timeless strolls through dark (neonless) streets.

Nothing has been more life altering than the stories told by survivors of Nazi rule. There have been nights when I woke up in a panic from nightmares that were too real, my sheets soaked with sweat. My personal process is one of awakening. I want so much to hang on to all of my American idealism that makes Germans see me as naïve. I want to believe that the core of all human beings is goodness. But as each experience passes through my heart I have to acknowledge that I really was naïve! No matter how good we claim to be or want to be, there are situations where average people turn into monsters that epitomize the concept of evil. It is much more difficult to separate oneself from reality when the pictures on the TV tube are the same pictures just outside your doorway. It is much more difficult to imagine myself separate from the stories being told when the storyteller is holding my hand.

I am affected intensely by every trip into Eastern Europe. The fact that they existed under Soviet rule for forty years, so close to the West, has created this unbelievable sociological microscope. I spoke to a man who told me he was angry that a Western company was allowed to build a water treatment plant in his village. His water comes from a well, but now he is required to pay to have his house connected to a system where he will be forced to pay for water so some Western company can make a profit. Western corporations have descended upon the East like a plague of locust, waiting to privatize everything like water and healthcare so they can make profits. Through a translator I spoke with a young man who was handing out free Philip Morris cigarettes to young 12 to 14 year old boys. He told my German friend that he was specifically instructed to target young boys because they would be the wage earners of the future. They want to take advantage of the lust that exists for everything American. From this vantage point the concept of a “free” market seems more like the freedom to profit from other people’s suffering. Sometimes I feel a great sense of shame!

A friend who learned of Rob’s fascination with planes, gave us directions to a park that borders Tegel airport. We entered Jungfernheide, at an entrance from Bernauer Str. This put us at the end of one of the major runways. We carefully placed our blanket as close to the runway as possible, the concrete ending about ten feet from where we were. Then lying on our backs, we waited for the next plane to depart. I thought Rob was going to have a heart attack, overwhelmed by the joy he felt.

Rob had been obsessed with aviation since he was a young boy. Rob could identify a plane in the air. We used to sit on Black Sand Beach in Marin County, California, watching the planes taking off from SFO. Rob knew the airline by the insignia that I could not make out from such a distance. “There’s the Lufthansa flight to Frankfurt,” he would say. Then he would tell me the type of plane, the manufacturer, the date of that particular plane’s release, and how many seats were on board.

The ground shook, the sound was deafening. Then suddenly that Lufthansa plane, that huge monstrous piece of metal, way too heavy to possibly be able to fly, would magically rise into the air just seconds before it would have crushed us on our blanket. If this was not on Rob’s bucket list before, it was surely added that day, with a check marking it’s completion.

We could see the belly of the plane, all the wheels that allowed it to land safely and the enormous engines that propelled it into the air. The adrenaline rush was ten times better than that of any ride in an amusement park. Even though we understood that the plane would not really run over us, we felt a rush that only comes with extreme danger.

We knew we weren’t supposed to be there. We knew it was illegal. But in the not so distant past, it was also illegal to stand upon the Berlin Wall. It was also illegal to pass from West Berlin to East Berlin.

We were living in a bubble that would soon burst. We understood that we did not have the luxury of waiting to fulfill our dreams. We came to Berlin with the courage of someone who had looked into the face of death, and were greeted by millions who had looked into the face of tyranny, and spit in its face. We had climbed through a hole in the fence, like two teenaged boys oblivious to any consequences. We survived and no one got hurt. We were encouraged by our Berliner friends who shared our sense of urgency. We knew that the rest of the world would find it difficult to understand that in the summer of 1991, the rules and logic of the rest of the world did not apply to Berlin.

Rob and I occupied a child’s room in a Wohngemeinschaft in Berlin’s Bohemian neighborhood, Kreuzberg. Jasmine was in Ireland visiting her grandmother for the summer. Her mother Camille was responsible for Rob and Bob coming to Berlin in the first place. She had invited Rob to Jasmine’s room the summer before, after they had finished a yoga intensive together in the Greek islands. Rob’s visit then was an epiphany. Less than one year later we stood together in the same room, validating Rob’s revelation of moving to Berlin. In Kreuzberg we found the soul of Berlin.

Our room was above a Turkish bakery and grocery store. On Sunday mornings we were awakened by church bells and the fragrance of Turkish pide bread. On weekdays all shops were forced to close at 6 PM, but the Turkish grocery stores flouted the law by taking an hour or more to bring in the produce from the sidewalk bins. If someone needed something after hours, it was understood that it could be acquired at a Turkish shop.

The entrance to our Wrangelstraße home was typical of the neighborhood. We entered a courtyard through a large open gate big enough for an automobile. It was partially obstructed by the long bins of fruits and vegetables from the Turkish shop. The stairway to the top floor was merely functional, with no concern for esthetics. The decades of neglect allowed all the scars and blemishes to tell their stories. There was no attempt to flood all the corners with light in fear of a lawsuit if someone should fall. It was ganz normal. The center of each stair was worn to the point of sagging, making me wonder who walked on them 50 or 100 years ago. I was overwhelmed by their beauty. They were romantic in a way clean, polished, refurbished stairs or buildings could never be, because their history had not been erased.

The communal toilet and bathroom was huge compared to American bathrooms. Near the back of the room was a washing machine flanked on both sides by wooden clothes drying racks. Three quarters of the way back on the left stood a grand old clawfoot bathtub. One quarter of the way back on the same side was the toilet. On the right side were two kitchen chairs facing the tub and toilet. For efficiency, there was no lock on the door. Why should anyone be forced to stand outside the door from a room that provided three functions?

The first time I took a bath felt like a college hazing. Just as I lowered myself into the tub, Heiner came in and sat on the toilet, casually beginning a conversation. Then his three year old daughter ran to the side of the tub, removed all her clothes, then jumped into the tub with me. I laughed as I explained to Heiner, that I would possibly face criminal charges if this took place in America. He responded, “Oh yes, America, where people sue other people when real life happens.”

One of the duties of the residents of the Wohngemeinschaft, was to cook dinner for the other residents. On the day that job was delegated to me, I spent the entire afternoon cooking red cabbage with apples from scratch. When we sat down to dinner, Heiner began to scream at me. “Why would I want a man to come all the way from California to Berlin, to cook a meal exactly like the meals my mother cooked for me my entire life?” If Heiner intended to insult me, he failed! All I needed as a compliment, was to know that my Rotkraut mit Äpfeln was exactly like his mother’s.

In my heart I’m back in Danville, Illinois, with the fragrance of Lilacs riding on a gentle warm May breeze. The moment we cross the bridge into East Berlin, my mind wanders back to my childhood. It’s the only reference I have. It's as if everything in the east was frozen in time in the 1940s.

Treptower Park used to be nearly inaccessible from Kreuzberg, separated by an impenetrable iron curtain. Now, for Berliners, each time they cross into the east, it feels as if they are tearing down the wall all over again.

Camilla invited us to take a Saturday stroll through Treptower Park. The first thing I noticed was how green the grass was. Unlike the manicured lawns of The Tiergarten, the grass was just beyond the point where a western landscaper would send in the lawnmowers. I noticed honey bees hovering above dandelions, while occasional breezes would burst the puff balls, sending hundreds of florets sailing through the air. The simplicity of life here is inescapable juxtaposed to the hectic drone of West Berlin. It’s like The Wizard Of Oz in reverse. Color to black and white.

Rob and I immediately noticed that we were noticeable! Our clothes as well as our demeanor, screamed American. The attention was polite, sometimes accentuated by a gentle smile of approval. When Rob did a headstand while practicing yoga on the lush green grass with Camilla, the attention became intense. It was then I remembered Ulf’s stories of trying to escape to the west. It occurred to me that there must have been an understanding that anything out of the ordinary would not be tolerated. Not even a public headstand in a park.

A man passed us on the path pulling a farm wagon with six children inside. Many of the women wore hats and clothes that reminded me of WWII movies. Some of the buildings had bullet holes that made me question whether they were from WWII battles or Soviet occupation. Walking past an U-Bahn station, I marveled at the lack of advertising. Any signs were simply functional, telling us how to buy a ticket or get where we were going. No one trying to sell us anything. In the absence of subliminal advertising suggestions, I realized I already had everything I need.

By June 1991, Rob and I had saved enough money out of our budget to travel to Prague for a few days. It was our second trip into what had been the Soviet Block, our first being Budapest in 1988. The two cities had shared a festering hostility toward their occupiers throughout the occupations. In Budapest we experienced the occupation, in Prague we experienced the liberation.

Traveling by train in Europe was always an adventure. We always tried to find a compartment car with interesting looking people, because we longed to hear the stories of their lives. When you have six people, three and three facing each other, knees almost touching, it’s impossible to remain aloof. Regardless of who our fellow passengers were, all of our stories were framed in the context of the Berlin Wall coming down. We got a lot of advice of what to see and how to survive in Prague.

We had to change trains in Dresden, arriving in Dresden Hauptbahnhof midday. We bought sandwiches in a kiosk, then sat chatting with a German backpacker. When we mentioned Prague, he became animated, his voice rising an octave. “You are in the wrong station” he screamed! When we showed him our tickets, he pointed to the small print that indicated our point of departure. It read Dresden-Neustadt station. Our train was to depart in ten minutes and we were in the wrong station.

We ran to the main entrance where taxis were lined up waiting for fares. We immediately went into American Hollywood action movie mode. We jumped into the back seat of the taxi, throwing our backpacks in before us. We explained we had to catch a train at Dresden-Neustadt station in ten minutes. “Mach schnell Bitte!” Our driver took the cue, immediately taking on his James Bond persona. We drove through a couple of red lights, then screeched around a corner where the iron pillars supporting the train tracks above seemed to be on a collision course with the side of the taxi. But the driver regained control inches before impact. We arrived at the station exactly at our departure time. Rob threw some American dollars into the front seat as we gathered our bags, then ran through the station to the assigned track. The train had begun to move, so just like in the movies, we ran beside it, grabbing onto the handle, then pulled ourselves onto the platform.

Out of breath, we took our seats in the compartment car, then laughed out loud at the absurdity of what we had done. Just when we had regained our composure, the conductor came to stamp our tickets. The man smiled gently as he reached out to collect our fares. His face was covered with hair, with only the eyes and lips visible. He stamped our tickets, then gently patted us on the shoulders to acknowledge our discomfort. A regular commuter explained that the conductor had Hypertrichosis (Werewolf Syndrome) that often went untreated in the east. Rob and I both closed our eye for the rest of the trip to Prague. We’d had enough excitement for one day.

If East Berlin was a time trip back to the 1940s, Prague was a trip in time back to the 13th century. On one of our discovery walking tours, we heard loud voices raised behind a huge wooden door that seemed to be an entrance to an eating establishment. We open the door to peak inside. Beneath cathedral ceilings, the room was lined with long thick wooden tables, with wooden benches that seemed to be cut from the same trees. The air was thick with smoke from the cigarettes and pipes of the all male inhabitants. We closed the door quickly to save our lungs.

The currency exchange rate in Czechoslovakia was insane. We got 39 Czechoslovak koruna for one dollar. Subways, buses and trams cost 7 cents. Loaves of bread were 8 cents and large chunks of cheese were 10 cents. Finding food was always difficult because of the intolerable cigarette smoke in restaurants. We always gravitated to vegetarian restaurants, because they were often smokefree. In Prague, we found a Kosher restaurant in the Jewish Quarter near the Jewish Museum that fit the bill. For breakfast, we treated ourselves to the buffet at the Intercontinental Hotel for a whopping $10.

In late July our hosts Ulf and Joachim told us to keep the evening of Friday August 2, 1991, free. They had planned a surprise for us. We always enjoyed trips in Joachim’s car, since we were limited to public transportation. Joachim drove us to a part of Berlin that was unfamiliar. Ulf giggled as he clutched a backpack he described as part of our surprise. When we were stopped in a line of traffic their surprise was prematurely revealed. It was not difficult to understand where the evening was headed after a tall man in black fish net stockings and very tall black platform shoes, brushed against the car. Suddenly we were surrounded with variations of imitations of Rocky Horror characters.

We were at the Waldbühne, for a celebration of the 55th anniversary of the opening of the historic amphitheater. It was built by the Nazis to impress the world at the 1936 Summer Olympics. We took seats about half way up from a screen that resembled a drive-in theater screen from my childhood. Both Rob and I had seen the special Friday midnight showing of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, at the theater in Georgetown, when we lived in Washington, D.C. But nothing could have possibly prepared us for a showing in an amphitheater that holds 22,000 people.

Ulf came prepared with newspapers, rubber gloves, water guns, rice, flashlights and toast. It was fun to hear the audience talk back to the screen, in a country where English is a second language. It was especially touching to watch Ulf, like a child at Christmas. Just a few years before, in East Berlin, Ulf had to hide his smuggled Abba albums, because they were banned by the DDR. On that Friday night there was a special palpable energy in that particular presentation of the Rocky Horror Picture Show, because that audience was filled with thousands of “Ulfs” celebrating a new life and a new found freedom.

When the words, “there’s a light” reverberated from the giant speakers, I had tears in my eyes. I remembered Market Street in San Francisco, after the murder of George Moscone and Harvey Milk. Not since that candle light procession, had I seen that many thousands of people holdings lights above their heads. I think it was the combination of the lights and the connectedness we all felt. We were all there for more than just a movie. We were a mixture of people of varied experiences who had been brought together by an historic event. Now, in a place that had once been used to promote evil things, it seemed the irreverence of the movie was there to help break the last threads of authoritarian control.